Everything you wanted to know about Alexander’s depressed larynx but were afraid to ask

I have seen recently a few articles written by some Alexander teachers about the supposed “dangers of having the head forward and up”. This reminded me of how little the modern AT schools train their students to analyse rationally and experiment practically with the written premises of the Technique of direction of the general use of the self in relation to functioning and to the manner of reaction. This, and a question1 about the same subject by one of the teachers of the modern Alexander technique undergoing post-graduate training with me prompted to re-write this old article to offer an example of a reasoned analysis on a reasoned plan.You remember certainly that F.M. found he was “pulling back the head”, “depressing the larynx” and “sucking his breath in”2 in the introduction of “The Use of the Self”.

I have seen recently a few articles written by some Alexander teachers about the supposed “dangers of having the head forward and up”. This reminded me of how little the modern AT schools train their students to analyse rationally and experiment practically with the written premises of the Technique of direction of the general use of the self in relation to functioning and to the manner of reaction. This, and a question1 about the same subject by one of the teachers of the modern Alexander technique undergoing post-graduate training with me prompted to re-write this old article to offer an example of a reasoned analysis on a reasoned plan.You remember certainly that F.M. found he was “pulling back the head”, “depressing the larynx” and “sucking his breath in”2 in the introduction of “The Use of the Self”.

This discovery and all the following discoveries described in the first chapter of the book were not made by scanning or deepening his feeling sense, but by observing the concerted movements of the different parts of his organism in action in a mirror when he was guiding himself with definite verbal instructions3: this was conscious guidance.

Conscious guidance and control was never fully abandoned by Alexander, even if he decided to teach using more and more sensory experiences (subconscious guidance) transmitted through authoritarian manipulations. In his last book, in 1942, the “new principle” borrowed from Ralph Waldo Trine in the first book, msi (1910)4 makes a remarkable entry:

In this whole procedure we see the new principle at work, for if we project those messages which hold in check the familiar habitual reaction, and at the same time project the new messages which give free rein to the motor impulses associated with nervous and muscular energy along unfamiliar lines of communication, we shall be doing what Dewey calls “thinking in activity.” (Alexander, F.M., “The universal constant in living, Chaterson L.t.d., 1942, third edition 1947, p. 91)

I had imagined that, because he was talking about incorrectly concerted movements which he could see in the mirror and not movements he could feel (everyone knows that feelings cannot be expressed in words), my teachers would be able to describe these movements in words and schematic forms, but I was disappointed. I heard things like “nodding the head by a release of the neck muscles will free your breathing“, and other authoritarian comments, but nowhere could I find a rational explanation of the relationship between the depressed larynx and the pulling back of the head. I do not think that anyone knew that “depressing the larynx” was a particular movement.

Alexander himself never made plain what he saw in the mirror about his larynx and the expression “depressed larynx” never transmitted a clear signification to me. Curiously, I could not find anybody to give me a clear description of the linked conditions Alexander was starting with and even less a rational explanation during my own training course. The first generation teachers that I met at the time were curiously evasive about the subject.

Everybody acted as if “depressing the larynx” or “pulling the head back” were obvious, unambiguous actions, and no one had made any experiment to test what they could be nor how they were precisely related. It is clear that if you possess a ‘solution’ for all ailments, a solution which you can transmit subconsciously by touch, there is no point in investigating Alexander’s problem!

Alexander had started investigations in a new field of practical experimentation upon the living human being (Alexander, Uos, p. 15), but by the time I started my training, the practical experimentation upon oneself brought about by using definite instructions of movement had been transformed in authoritarian teaching of the desired result from a knowing teacher to an intentionally passive student.

The disappointment of not receiving the basic justification of Alexander’s connected starting points, and the fact that I was translating Alexander’s books (a translator is supposed to understand the meaning of the text he translates), explains why I decided it was necessary to ‘do the work’ to clarify the meaning of the “depressed larynx” and its relation to the pulling back of the head.

By using Delsarte’s6 action coding system7 and some principles of geometry applied to physiology and physics borrowed from N.A. Bernstein, I started a reasoned analysis on a reasoned plan8 to find a practical procedure of experimentation which would give the meaning behind Alexander’s written word: here is what can be said about my examination of the problem after twenty years of study.

What is the evidence at our disposal?

When the young Alexander started studying his movements in the mirror, he did not know what he wanted to see. This is what started his path of inquiry.

As he explains, he had to learn how to see to begin to realize that there was something WRONG in his way of reacting and using the different parts of his anatomical structure

“Standing before a mirror I first watched myself carefully during the act of ordinary speaking. I repeated the act many times, but saw nothing in my manner of doing it that seemed wrong or unnatural. I then went on to watch myself carefully in the mirror when I recited, and I very soon noticed several things that I had not noticed when I was simply speaking. I was particularly struck by three things that I saw myself doing. I saw that as soon as I started to recite, I tended to pull back the head, depress the larynx, and suck in breath through the mouth in such a way as to produce a gasping sound. After I had noticed these tendencies I went back and watched myself again during ordinary speaking, and on this occasion I was left in little doubt that the three tendencies I had noticed for the first time when reciting were also present, though in a lesser degree, in my ordinary speaking. They were, indeed, so slight that I could understand why, on the previous occasions when I had watched myself in ordinary speaking, I had altogether failed to notice them. This could hardly have been otherwise, seeing that I then lacked experience in the kind of observation necessary to enable me to detect anything wrong in the way I used myself when speaking” (Alexander, F.M., “The use of the self”, Integral Press 1932, reprinted 1955, p. 6).

Alexander is saying that he lacked experience in the kind of observation necessary to enable him to detect what was wrong in the way he used himself. He was seeing himself in the mirror but could not detect anything wrong.

And so did I: one hundred years after Alexander’s ‘evolution of a technique’, nothing existed in the lessons or the training courses to develop a method of visual observation of the movements of the parts. Alexander had taken his method of visual observation to his grave. The ‘parts’ Alexander is talking about were not even defined properly.

I realized that we were more blind than Alexander was when he began his experiments with conscious instructions of movements. Our visual impairment was different in nature; it was voluntary and customary. The modern Alexander technique had invested so much in touch, that no one considered Alexander starting point as worthy of interest. I started to think that, by replacing visual observation by touch, we would never develop the power to see which led Alexander to invent ‘thinking in activity’.

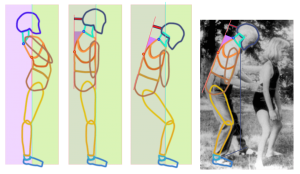

N.A. Berstein cinematographic study of the French runner Ladoumegue: raw material for quantitative analysis and mechanical interpretation.

This is why I found in Bernstein’s techniques of cinematographic study of movements9 a ray of hope.

Bernstein demonstrated beyond doubt that films and photographs of gestures can be subjected to quantitative analysis and to mechanical interpretation. Unfortunately his processes of ‘kymocyclography’ were so complex that they were reserved for laboratories with large fundings: also with the unbelievable mass of data they provided, they could not help the individual reason to improve his use of the self.

And suddenly, by chance, I discovered that François Delsarte had invented a similar system, but how much more easy to set up, which permitted an approach of the real goal of investigation: biomechanical analysis of the processes of movement of the parts.

The basis of the Delsarte “action coding system” is

- to designate topological landmarks on the different parts of the anatomical structure of the subject (the ‘parts’ are clearly defined bony structures or ‘levers’ as Delsarte used to call them),

- to compare the geometrical relationships between the landmarks, and

- to infer which geometrical relations between these parts may lead to appropriate movement and functioning.

This process does not rely on the kinesthetic or proprioceptive sense, but on plain visuospatial analysis: “you start believing in what you see and not in what you feel”.

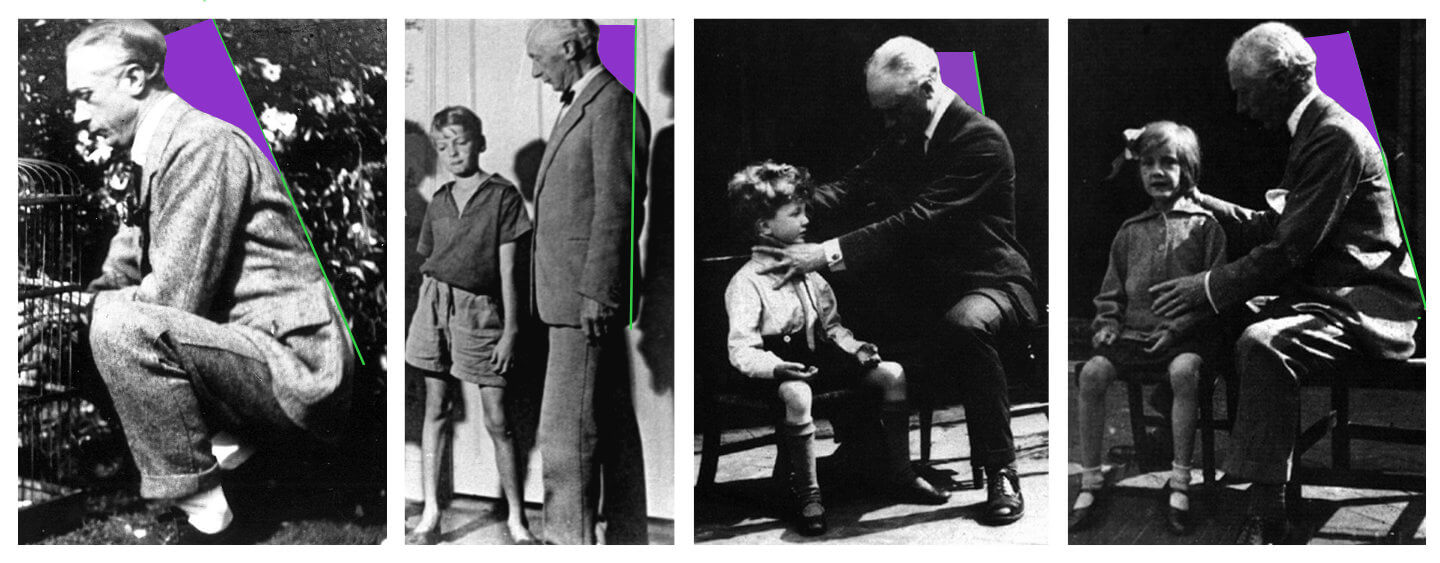

This explains why I started to get interested in every photo showing Alexander manipulating a student. I wondered if it was possible to assess what he wanted to do with his hands in terms of geometry, or, as he used to express it, in terms of relationships between the parts.

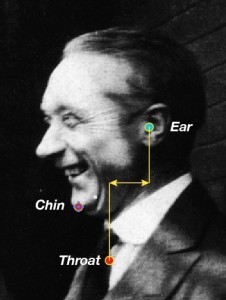

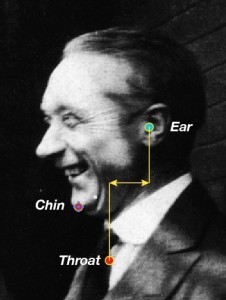

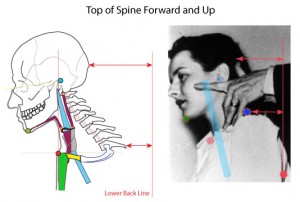

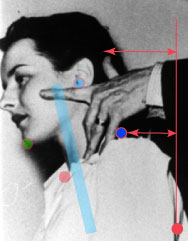

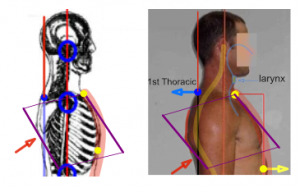

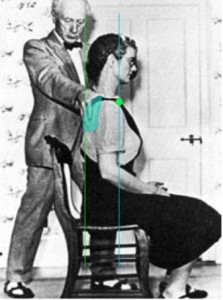

On this picture, I have placed five dots, a red line and a blue tube. The five dots are anatomical landmarks chosen on different bones:

- the ear, (nearest spot of the top of the spine)

- the throat, (top of the sternum)

- the chin

- the first thoracic vertebra

- the middle of the thoracic curve.

The red line marks the back of the lower torso (when lengthening) and the blue tube is a representation of the airway tube (back of the nose to hilum of the lungs).

The dots and lines give a diagrammatic idea of what result the manipulations tended to. It is a picture of the conception which Alexander used as a model of the future conditions of use and functioning. With such a conception or dynamic representation, it is possible to analyze the outcome of a person’s directions at a moment in time.

Coming back to the photo presenting Alexander’s head on the sagittal plane (Alexander’s profile), it is not possible to see the larynx. But we know that the larynx is part of a long tube which upper end is attached behind the nose, suspended to the lower jaw and which lower end pass behind the sternum before being joined with the lungs at the height of the second and third thoracic vertebra. Therefore the larynx is subjected to the geometry of the head in relation to the torso: by analysing the relative position of the head and torso and by comparing the relationships with the one he was promoting when giving a lesson to a student, we can get an idea of the mechanical flattening the tube can be subjected to.

On this image of a retrognathic mandible (lower jaw pulled back toward the neck) with a blatant double chin, it is frightening how far back Alexander’s Ear (auditory canal) is relative to his Throat (top of the sternum).

On this image of a retrognathic mandible (lower jaw pulled back toward the neck) with a blatant double chin, it is frightening how far back Alexander’s Ear (auditory canal) is relative to his Throat (top of the sternum). This comparison between appropriate and faulty movement of the ‘levers’ of the anatomical structure is easier to achieve if you already have a ‘positive determination‘ of what ‘good general use of the parts of the anatomical structure’ could look like. Unlike many, I think that Alexander was showing such positive determination, especially when he was manipulating his pupils. Therefore we have a great advantage on the young Alexander, because we can still learn to see by noticing the difference he achieved in terms of use when he was consciously directing the general use of this organism.

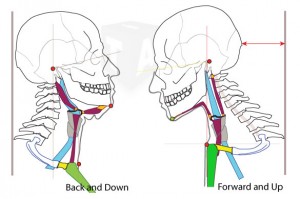

Following this process of reasoned analysis, I propose to study the differences in two instances of Alexander’s profile. According to the simple action coding system shown above, I will start by affirming that, on the left picture, Alexander is caught with the Head Up and Back relatively to the torso and that his larynx is depressed. Conversely, on the right, you will see (shortly) that he exemplifies the famous “Head Forward and Up”.

The purpose of this paper is to present the rational basis of such affirmations.

Note how the double chin disappears on the image on the right. The local effect of the different geometry on the neck and upper airways may not be obvious to you yet (the windpipe is retracted at its top on the left image while it is extended forward on the right image), but after reading this paper, this condition will be clear for you to see in your pupils or in yourselves.

When Alexander was “consciously directing” his use of the different parts of the torso (picture above on the right), in a picture taken near the beginning of his career (1917), his torso-head relationship appears very different than the ‘habitual gesture’ we see in most untrained people when standing: the chin is much further forward from his chest and the the larynx is much less constricted than on the other picture.

His head is clearly forward and up relatively to his torso while on the image on the left, his head is just above the center of his torso exactly like this block analysis of the standing gesture.

In this paper, I will demonstrate that the fundamental change of carrying the head forward of the torso is only possible through a new coordination of the parts of the mechanism of the torso, and not, as it is often advertised nowadays, by a release in or of the neck. Alexander conception of the lengthening of the torso must be re-evaluated and our practice must certainly be recalculated.

The impact on the larynx

A certain use of the Head in relation to the neck , and of the head and neck in relation with the torso provides the best conditions for raising the standard of functioning…

For now, if you imagine the airway tube going up from the hilum of the lungs, nearer to the back than the front of the thoracic cavity, at the height of the second or third thoracic vertebra, to the back of his nose (the upper airway composed of naso-pharynx, oro-pharynx, laryngo-pharynx and trachea or windpipe), you must realise that in the geometrical conditions displayed on the right (“good use”), this long collapsible tube will be extended forward and up and not bent back and narrowed like in the use of the head and torso on the left.

This bending or opening of the airways tends to accredit the thesis that “head forward and up” could be a positive use of the anatomical structure, improving not only the general balance but also the breathing and vocal mechanism. We are going to explore this issue much further to understand Alexander’s claim that modifying the orientation of the different parts of his articulated torso changed the relation between his torso and head and ‘cured indirectly’ his voice problem.

An quick example of a reasoned analysis

Before starting a reasoning consideration of the causes of the conditions present10, I would like to show how easy it is to establish a reasoned analysis of the mechanical use of the self on a picture or in the reflection of a mirror.

On this photo of a flamboyant middle aged Alexander, we can now see that his stature is lengthening but that something is amiss. As a rule, I always communicate the ‘good relationships’ before getting to the geometry which needs conscious guidance (means-whereby instructions) to improve.

- His Ear is UP (away from the Throat —red dot on the top of the sternum bone)

- his Upper parts of the arms —green dots on the head of the humerus—) seem to be slightly forward of the Throat (a symptom of a widening upper back),

- the head is not pulled down toward the back as the Chin is directed toward the throat (he is “nodding is head down”),

- the Throat is very high (the top of the sternum is above the line joining both Upper Part of the Arm).

He looks tall and erect.

Yet again, we can see the double chin11 and the head is not forward but directly above the torso. The Ear (auditory canal) situated near the top of the spine (apparent only on a sagittal X-ray) is very far back relatively to his Throat.

We will see that from these criteria alone, we can safely deduce that the man is retracting the head relatively to the torso. The end result of his movements of the parts of the whole stature is that his head is Up and Back relatively to the torso, with the top of the windpipe pulled back and the larynx imprisoned far forward of the naso-pharynx (back of the nasal cavity and beginning of the airway tube).

He “looks tall”; nevertheless, this appearance is hiding the fact that, at this precise moment, he is not functioning to the best of his capacity.

In passing it is not negligible to mention that the picture was taken after 1930, long after Alexander invented his technique: we see that despite years of practice, he could still be caught in the act of reacting with the old erroneous sensory guided direction. The idea that one would “get it” after sufficient conditioning of the postural reaction or after having received the “correct sensory appreciation“12 seems to be refuted by the behavior of the master teacher himself.

The aim of this article is to help students reason:

- what *head forward and up* meant at the time Alexander started teaching and,

- what is the relation of the geometry between torso and head with the opening of the airways and the functioning of the breathing mechanism.

I am also going to explore the consequences —the connection which exists between cause and effect— of such end result on the two other ends that Alexander kept presenting as his concerted goals of the teaching of the use of the anatomical structure (Back-to-lengthen-and-widen and Neck-free).

In the individual the normal processes of education in the use of the anatomical structure are conducted subconsciously, certain instincts commanding certain functions, whilst other functions are conducted deliberately.

The effects of this haphazard process have either to be elaborated or broken down, according to the defects established by misuse of the mechanisms, and the first step in re-education is that of establishing in the pupil’s mind the connection which exists between cause and effect in every function of the human body. (Alexander, F., M., “Man’s supreme inheritance“, 1910, Charterson Ltd, Methuen & Co., p. 141.)

I will explain how this particular geometrical relation between head and torso is related to both his habits of shortening the stature and gulping in air. We will see how a poor geometry of mechanical advantage of the torso is sufficient on its own to create a vicious circle that was bound to affect his voice in time.

Conception or misconception of the relationship between head and torso

I will now start a reasoning consideration of the cause of the conditions present, i.e. a retracted head [toward the center-line of the torso], a tendency to suck in air, and a depressed larynx. I did not go really far to investigate the “cause”: I just carefully examined the conceptions of the use of the self proposed by the Alexander technique presence on the web.

In order to get my bearing, I just followed the quote below:

“In the performance of any muscular action by conscious guidance and control there are four essential stages :

- The conception of the movement required

- The inhibition of erroneous preconceived ideas which subconsciously suggest the manner in which the movement or series of movements should be performed“;

- […]. (Alexander, F., M., “Man’s supreme inheritance“, 1910, Charterson Ltd, Methuen & Co., p. 141.

Some of you may think that the conception of the movement required can only be obtained by the repetition of correct manipulations by an expert teacher. I started to question this belief long ago because Alexander certainly did not form his conception in this way. According to his books, he had to:

- reason out new verbal instructions because he inferred that what saw in the mirror was not conducive to good use and functioning, and

- include the correct “means-whereby” so that the process of carrying them out involved the satisfactory use of his mechanisms as a whole 13

A detail troubled me even more. All the first generation teachers had extensive manipulation-work done to them by Alexander, yet none ever wrote a paper explaining in reasonable terms the conception that lies behind Alexander’s choice to indicate the head-forward-and-up result as being the main symptom of good use. While they all repeated with authority that the head-forward-and-up is a sure sign of good coordination, none really did explain why nor what it really entails. When I started to play with the action-coding-system analysis of the photographs of the senior teachers, I became even more puzzled.

Head forward and up, yes, but from where?

- The third of August 1934, Irene Tasker made a report of a lecture Alexander delivered at the Bedford Training College. It is the only trace of Alexander explaining from where the head should be taken forward and up, i.e., a part of the back of the torso:

“What this young lady is doing now is a very difficult thing to do. She is directing her head forward and up from here (Alexander indicates with his hands a part of her back), he knees forward and the hips back, and that the only way you can get your antagonistic pulls”. (FM Alexander, “*Articles and Lectures”, “Bedford Physical training College Lecture”, Ed. Mouritz, p. 177 – 178).

I never heard a senior teacher describe the new use of the head relatively to the torso in such a precise form, i.e. in relation to an explicit landmark. Nor did any demonstrate in his/her use such a relationship.

This tend to show that receiving a correct sensory experience does not in itself create a clear conception of the movements required in the torso to produce such a result, not anymore that it constructs any solid guidelines in the self-guidance of the series of movements (means-whereby) necessary to obtain the result.

I understand that this statement may seem very arrogant, but I have met many of these teachers and I have a wide collection of photos in which they are seen giving turns or posing for a photograph with their head “back and up” (and sometimes back and down) relatively to the back of their torso. Near the end of this paper, you will see with your own eyes how Alexander exemplified Head Forward and Up from his back: you will come back to this photo and wonder….

What I am discussing and talking about here is the conception of the correct manner of use of the different parts of the torso. What is the proper shape, the result you seek to achieve when you mould the pupil’s body14 with your hands? The conception is that mold as sure as there must be a plan prior to its execution.

Alexander believed that this conception should be conscious.

But granting the subconscious its fullest degree of merit, we are forced to recognize its serious limitations in the mode of life (civilization) with its ever-changing environment which human progress demands. We must have a guiding principle without these limitations, to enable us to adapt ourselves much more quickly to the new environments which are inevitable in the progress of civilization towards its legitimate goal.

We must have something more reasoned and definite than that which subconscious direction offers, and so we come to the need of reasoned guidance. (Alexander, F.M., “*Man’s supreme inheritance*”, Chaterson Ltd 1910, reprinted 1946, p. 112)

Despite what many are preaching today about their “capacity to accurately feel and allow the correct use to be transmitted to their pupil“, intimating that they are allowing a subconscious, natural, embodied cognition to come out of non-doingness where the right-thing-does-itself without any planning or critical thought, it is amazing how loud the conception of the shape they are imposing on their pupils shouts from the photos of them working with their pupils. Further along, I will show a random collection of pictures of modern teachers and pupils and you will see that the mold is curiously fixed across countries and time and certainly not allowing each pupil to express its own ‘nature’.

As a reader of Alexander’s books, I never thought that the technique was a mean to express a fabled ‘nature’, but rather a cultural, reasoned guidance necessary to avoid the downside of the preliminary inertia of mind which tends to stick to the most salient feeling and sensation with no regard for the functioning of the whole.

Because of the strength of the subconscious conception transmitted by the hands-on moulding of the body, I will not consider the discourses which place “Head-forward-and-up” in the class of ‘intangible phenomena’ or spiritual non-efforts. As you well know, I am teaching a rational technique (mental principles and rules of construction) and tangible means whereby.15.

Of all the conceptions which lead to the conditions of head-pulled-back and depression of the larynx the main one is to be found in the modern ideas (conceptions) regarding the lengthening of the stature (looking tall and erect) and mechanical advantage (the use of the torso that should feel light and good!).

During my investigations, I realized that I had subconsciously learned during my training days through the teachers’ manipulation (hands-on) and table-work (sometimes called semi-supine or constructive rest) a perverted notion of Head forward and up which clashed with the other criteria of good use, i.e. a prevention of a depressed larynx and of a reduced mean thoracic capacity. Nowadays, I call this conception the “plumb-line use of the torso and head”.

The story of the modern conception of the balanced body

During the reasoning I am going to present, we should not forget that any conception of the position of the cranium relatively to the torso affects not only the whole spine (shortening the stature), but also

- the angle of the airways tube between the back of the nose and mouth and the lungs, and,

- the volume of the thoracic cavity.

In the “Use of the self” Alexander explains that he found that all these defaults, the geometric one (the retraction of the head relatively to the torso and the diminution of the mean thoracic capacity) and the functional one, i.e. sucking in or gulping in air, were directly related: for him, they had both to be checked in order to improve the condition of the voice and breathing mechanism.16

This is all well and good, but Alexander does not define in writing what he meant geometrically by “the tendency to put the head back“. We will see that, to this day, it is all but clear for his teachers.

Understanding the secondary symptoms, i.e. the depression of the larynx and the reduction of the mean thoracic capacity, is going to help us:

- realize the importance of a clear conception of Head forward-from-what and of a new geometrical relation between torso and head, as well as,

- define what Alexander called “back to lengthen”.

This link between the breathing mechanism and the carriage of the head in relation to the torso has not received the attention it deserved. It is at the root of Alexander exploration of the conscious use of the mind and it is the yardstick which can help us to reason out which conception of the use of the head in relation to the torso could be advantageous and beneficial.

The plumb-line misunderstanding

It is easy to replicate Alexander’s habitual, spontaneous reaction by arching the top of the torso back to pull the head back toward a vertical line passing by the middle of the back of the torso. Alexander called it “retracting the head” relatively to the back of the torso and he linked that habit of reaction to a common conception of lengthening the stature known as the “drill-sergeant’s chest” (Alexander, msi, p. 89) and the “plumb-line” monstrosity (Alexander, ucl, p. 56).

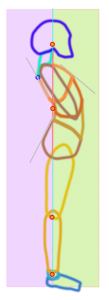

Before we start to examine the modern Alexander technique conception of going up which may lead to a depressed larynx, I would like you to observe the old “drill-sergeant plumb-line” description presented by Alexander in his first and last books.

I have added a few of Delsarte’s “psychological instruments“, i.e. colorized spots and geometrical lines which are not on the original photo — on this photo; the only line present on the original is the plumb-line itself, the black line going through the Ear, the 1st cervical vertebra and the ankle joint.

The purpose of the colorized visuospatial instruments is to help place different anatomical landmarks (definite spots on the bones) and geometrical lines, in order to consciously control the relations between the bony structures of the torso.

According to Alexander, this man is ‘lifting up‘ the chest. I do not find that this label adequately describes the use of the different parts of the torso. The expression translates quite well the intent of ‘going up’ which is at the source of the plumb-line conception, but it does not convey the movements of the top of the torso relatively to the movements of the middle and bottom of the torso.

This man is ‘lifting up’ the chest by pulling the top part of the torso back relatively to the middle of the torso: he is voluntarily arching his back by pulling the top of this back back.

Presenting such an extreme picture has the advantage to show clearly:

- how the line of the sternum (front part of the torso) corresponds to the top of the lumbar line (lifting the chest back toward the middle of the torso),

- how the spinous process of the first vertebra (blue dot) is pulled back behind the sacrum line (pulling the top of the torso backward toward the middle of the back).

There is a drawback though with such exaggeration. It is that no Alexander teacher would imagine being caught in such misuse of the parts.

Now that you have a clear and exaggerated conception of poor use, I will introduce the modern conception of good use which teachers of the modern Alexander technique put forth in their papers or websites.

In this way you may understand why I consider erroneous conception the modern attempts at representing the human anatomical structure. This is not an opinion, but the result of a process of experimentation with the “plumb line skeletons” that many teachers of the modern Alexander technique use in their teaching to depict good use. I will come back to this in a moment.

Unfortunately, this same erroneous conception or representation of the relationship between the head and torso has contaminated the servile medical copyists in their production of images for medical education: I intend to demonstrate that all the medical representations of the human upper airways are recreating the same incorrect retraction of the head relatively to the torso.

During my training days, no one thought to tell us —the students— that the academic anatomical iconography we were using to learn anatomy was presenting bad use! As you will see, it is more than obvious that our teachers did not understand the academical representation they were using to teach us anatomy. They were bringing into play medical charts without experimenting first what the representation really produced in practice. I think they never thought to experiment because they believed they had the correct sensory appreciation drilled into their sensory makeup.

It is only recently, with the advent of three-dimensional dynamic computer simulations and MRI of anatomical and physiological structures that the representations of the upper airways have started to show a very different picture of physiological appropriateness (good use) — much closer to the standard of functioning (good use) advocated by Alexander and, obviously, a different geometry between torso and head than the one people are used to see and consider ‘well-adjusted’ in the Alexander technique community.

The modern plumb line skeleton straighten the cervical spine

As I said, a number of modern Alexander teachers are presenting on their website or in different articles their idea of “good use“, “coordinated support” (Alexander, ccci, 1955 ed., p. 107) or “position of mechanical advantage” (Alexander, msi, 1917, p. 115). They are all trying to represent the correct stacking of bones, i.e. the End (end-result) they believe the modern Alexander technique is supposed to teach.

While I think that working with representations of the anatomical structure is a positive move in the direction of a rational or reasoned apprehension of the Technique, I must admit that I cannot understand their plumb-line skeleton other than as a result of a one-track idea with very little practical experimentation.

They all fell into the trap on confusing the finished product, the end result, with the attitude of inquiry which brought it to life: they are trying to get the student to digest a solution instead of developing the means to investigate the problem.

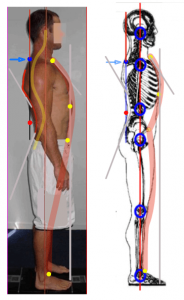

What is curious is that all these representations of the anatomical structure are made according to a type of “plumb line skeleton” in all aspects similar to the one which was presented by W. Conable (BodyMapping ®, or Andover Educators®). Such uniformity coming from different and unrelated groups of teachers in the States, the UK and Japan seems to argue for plausibility, yet there is an annoying fact: all their representations bear no little resemblance with the Drill-Sergeant profile criticized by Alexander.

This is a very common representation of what I call the modern plumb line skeleton; this one is from Body Mapping© found in the text of David Nesmith, “What every musician needs to know about the body“. http://bodymap.org/main/?p=276, but I could have chosen many others such drawings.

In this image, the author has provided a red line and shows how different joints are aligned on it. You are going to see that this red line is a plumb-line. The purpose of the arrow symbols at the back is not very clear to me, but it is possible to use the information at our disposal to create a practical experimentation and to test the model of “the Core of the body” , the “balanced body” according to Body Mapping.

This is the text which goes with the illustration:

“Our freest movement and consequently our freest breathing will only be available to the degree that we are balanced. Our bodies can be “postured” (shoulders back, chest out, tummy tucked, etc.), “collapsed” (slumped) or “balanced.” A “balanced” body utilizes our bony structure and postural reflexes for support of voluntary movement. It is that place from which movement in any direction is easiest. We experience balance when we make full use of mechanical advantage: bone in right relationship to bone“. (David Nesmith, )

This is what the Body Mapping bone on bone would look like: the plumb line posture! I have added a sternum line, a sacrum-line, a upper-lumbar line and the vertical projection of the front of the chest.

If you wanted to consciously control the model of bone in right relationship to bone, the simplest way would be to experiment practically by following all the criteria presented on the model and consciously direct your torso according to it.

I have not created the photo of the practical experimentation myself, I have just taken a picture on the Web depicting the plumb line posture advertized by the physiotherapists as “criterion of diagnosis of good posture“. You will see that the photograph on the left seems to have been exactly constructed on the model of the plumb-line skeleton of Body Mapping (or is it the reverse?):

- The top of the back of the torso (blue dot on the 1st thoracic vertebra) is slightly backward relatively to the lumbar curve apex (see red dot); this indicates a marked shortening of the thoracic spine;

- The shoulder-blade is protruding back and the upper part of the arm is behind the ribcage17; this indicates a marked narrowing of the upper back;

- The top of the spine (just under the Ear) is on the plumb-line and, as a result, the back of the Head is further back that the vertical of the top of the back of the torso; this indicates a strong retraction of the head relatively to the torso;

- The sternum is inclined back at the top (see the grey construction line) as a result of the collapse of the lumbar upper curve necessary to bring the 1st thoracic vertebra (blue dot) in line with the back of the pelvis.

As this article deals with the depression of the larynx as a consequence of a retracted head, I will focus my examination to the relationship between the torso and head.

It is clear that a lot could be said on the kind of use that this imaginary relationship between torso and limbs represented on the complete model would lead to, but I will develop on this vast subject in an other article.

How the plumb line model interferes with breathing and phonation

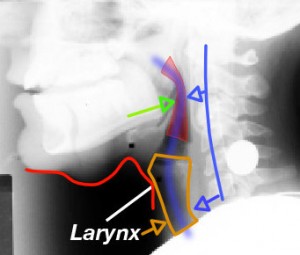

The bone on bone or plumb line model model correctly depicts a straight cervical spine —aligned on the red line—, which correlates with the position of the chin backward relatively to the front of the chest. To understand the connexion in cause and effect between the form and functioning (between the geometrical use and functioning) I propose that we look now at an x-ray of a person displaying the medical condition known as “straight cervical spine“.

One of the most important symptoms which you will see on this X-ray is that the bodies of the cervical vertebrae are piled vertically, (on a plumb-line) a sure symptom of a serious medical condition known as “straight cervical spine” associated with neck pain, breathing problems, vocal disphonia and sometimes muscles spasms.

I choose this picture because:

- it is exactly similar to the cervical spine of the bone on bone model, (the angle of the top of the sternum tends to indicate that this is a consequence of lifting the chest up and back),

- it shows the aspect of the cervical spine when it is compressed and retracted,

- it exposes what Alexander was doing to the geometry of his breathing mechanism when he retracted his head (the upper airway is colorized in red).

Exactly as in the Plumb Line Skeleton of Body Mapping, the Ear (auditory canal) is far behind the vertical line passing through the Throat (top of the sternum), the surest sign that the head is retracted relatively to the torso.

In order to underline the effect of such form (geometry) on functioning, I have colorized in red the upper airways and marked with a red arrow the bending and narrowing of the tube at the entrance of the Larynx. The backward movement of the top of the torso, head and jaw does not only retract the head relatively to the torso, shortening and compressing the cervical spine, it also causes a partial obstruction of the fibro-muscular tube of the pharynx and a sharp bend at the entrance of the larynx (see red arrow on the X-ray above).

Looking inside the mechanism of a bended and narrowed airway

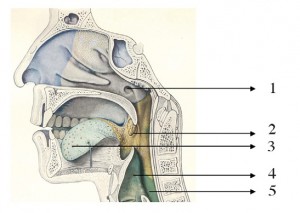

This diagram is a typical image used to teach the anatomy of the airways.

- (1) nasal cavity

- (2) Epiglottis

- (3) Tongue

- (4) Hypopharynx (and just under it, the beginning of the larynx)

- (5) Esophagus (digestive tract)

How are we to analyse this medical diagram of the upper airways?

When you look at a medical diagram on the internet or in a book, you should not accept it at face value. The reason for such comment is that most of the time, the doctors and scientists are not concerned nor knowledgeable about the best use of the parts. It is also clear that most representations used for medical training depict severe problems and dysfunctions to help students notice the problems.

Despite the accepted claim that “Understanding normal physiology provides the basis for recognizing abnormalities“18, in most anatomical charts found in medical texts, the general use of the head and torso is properly a misuse of the parts. Most x-rays you will find are also typical of a severe mis-use and dys-function.

And do not think that you are going to be on the safe side because a diagram or picture is proposed by a teacher of the Alexander technique in a book or article: very often they are just copying academic representations without having done the least work of research and objective experimentation of the mechanical truth of the diagram they employ.

It is necessary to train oneself to ‘read’ these representations and in this situation, the ‘action coding system’ is once again decisive in helping to make an appropriate judgment.

By now, you certainly have figured out my intent: this diagram does not present “good use” in all its ‘character’. It is an expression of a bad use with the head retracted and the airways collapsed: once again we are confronted with the plumb-line model.

- the bodies of the cervical vertebrae are almost piled vertically, indicating that the head is retracted toward the center of the torso on the sagittal plane,

- the pharynx is vertical, when we know that the other extremity of the airway, i.e. the hilum of the lungs, is in the back of the thoracic cavity: there must be a sharp bend after the larynx!

- the nasal cavity is clearly portrayed behind the entrance of the hypo-pharynx (we will see that in this condition the airways are not “free”) ,

- the Chin is lifted away from the Throat (the Head is therefore pulled down toward the back) and, finally,

- the larynx seems extremely high and protruding, a relative position that Delsarte demonstrated as being nocive for the phonation mechanism (there is an imbalance between the muscles suspending the larynx to the lower jaw -anterior belly of Digastric muscle and Mylohyoid muscle- and base of the skull (Mastoid and Styloid processes) -posterior belly of Digastric muscle and Stylohyoid muscle).

To support this interpretation, I present an x-ray displaying the same ‘plumb-line’ relationship between the head and torso: it is apparent that the head is retracted (a flat cervical spine is a very popular reaction) as the Ear (just above the top of the spine) is very far back relative to the front of the torso and the bodies of the cervical vertebrae are almost stacked vertically. There is a slight double chin (it is only small owing to the fact that we see a young singer).

At the same time, the larynx appears to be very high and bended backward: both conditions are present to foretell respiratory and voice problems. And indeed, this is the case as this example comes from a very interesting article on misuse of the “voice” by Soren Lowell which shows that the stimulus of speaking provokes a reaction in this subject who pulls the larynx-box UP toward the mouth every time she thinks of speaking aloud) direct link to the article by Soren Lowell.

On the x-ray it is therefore apparent that the back of the nasal cavity (1) — i.e. the entrance of the pharynx (the tube conducting the air to the larynx) — is backward relative to the opening of the airways (4) and larynx, inducing a bending of the tube in two places and an undue narrowing of the pharynx.

With or without manipulations, it is possible to coordinate the parts of the torso to extend the airways and prevent any bending or narrowing of the upper airways

For the airways not to be bended forward at the entrance of the larynx, the only solution would be to have the cervical column extending Forward and Up at the top.

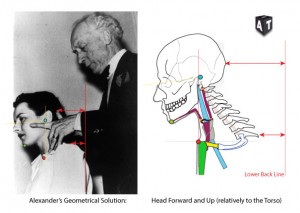

On this picture showing Alexander manipulating a young lady, we can trace the direction of the top of the spine in relation to the lower back line. It is clear that Alexander is organizing the pupil in order to free the upper airways (to “free the neck”) from any bending and obstructions.

If you compare with the x-ray above of the young singer with breathing and phonation problems, see how the red trace in front of the upper spine —the beginning of the airways, pharynx and larynx— are contorted due to the retraction of the head, neck and top of the thoracic spine. It is apparent that the tube is narrowed and flattened as a result of the particular geometry of the thoracic and cervical spine.

Therefore, we can see that when the head is retracted relatively to the lower torso, there is a narrowing and a flattening of the tube (pharynx and larynx) behind the nose and mouth.

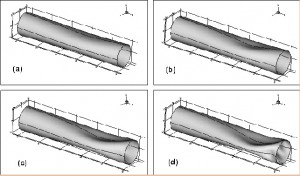

This picture of a bend tube does not depict a real situation: it is only a reminder of the geometry of a depressed tube.

We are now going to see what are the other mechanical conditions associated with the adjustment of the torso and head leading to a depression of the airways tube.

A biomechanical understanding of the “depression of the Larynx”

The geometry of the tube is not the only cause of the condition we are considering when helping a pupil find a solution to his misuse of the relationship between head and torso. There is also a functional problem associated with the habitual reaction of combating an obstruction of the airways by accelerating the speed of air.

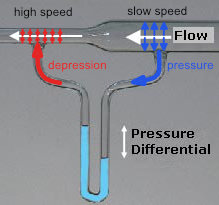

It is important to realize that there will be a flux of air running in the tube during both phases of respiration (inspiration & expiration). To understand the behavior of such a system, you have to know that this is a case of “fluid mechanics” (particularly of “fluid dynamics”).

Owing to the venturi effect (the law of “fluid dynamics which is applicable in this case), a flow of air passing through a narrowing of a passage is accelerated: with the acceleration, there is a reduction of the pressure which the fluid (air) exerts on the wall of the tube. This reduction of pressure is also called ‘depression‘ (in French depression means ‘lack of pressure’ or negative pressure).

Venturi found that the flux is constant in any open tube: as a result, a flux at slow speed generates high pression on the wall of the passage while any bend or constriction of the passage will generate high speed and low pressure (i.e. depression) on the passage walls.

When air flows through a constricted section, there is an increase of speed and a reduction in pressure.

On this example showing a flux of air passing through a tube with a reduction in size, the column of liquid is much higher on the side of the reduction in diameter because, as the speed is higher due to the reduction in size of the tube, the pressure becomes negative in the small tube. If the Flow was faster (or the narrowing more marked), the water would be aspirated into the thin tube on the left and would continue to do so until complete obstruction –because of the resulting negative pressure or ‘depression’– creating greater clogging and obstruction and therefore, greater loss of pressure on the walls and more water suction.

The experiment above has been done with a rigid tube (glass). It is interesting to understand what would happen in the case of a breathing mechanism made of collapsible tubes surrounded by hollow cavities full of fluid (sinuses) when the pressure is less than the atmospheric pressure due to both a bending of the tube and an acceleration (gasping in) of the air.

In a collapsible tube, we will see that the venturi effect (narrowing of the tube= increase in speed of air and corresponding decrease in pressure on the wall of the tube) also increases the tube deformation in the direction of:

- a narrowing of the airways, and,

- an irritation of the mucous membrane.

Instead of re-inventing the modelling of Alexander’s employment of the word “depression”, I propose to read the brilliant bio-mechanical explanation of M. Matthias Heil : “Flow in collapsible tubes” (see fluid Structure interaction problem).

Here it is:

Flow in Collapsible Tubes

The figure below shows the deformation of a thin-walled elastic tube which conveys a viscous flow (the direction of the flow is from left to right).

In its undeformed state, the tube is cylindrical and the ends of the tube are held open (think of a thin-walled rubber tube, mounted on two rigid tubes). As we increase the external pressure [from (a) to (d)], the tube buckles and deforms strongly. The reduction in the tube’s cross sectional area changes its flow resistance and thereby the pressure distribution in the fluid, which in turn affects the tube’s deformation.

This is a classical example for a large-displacement fluid-structure interaction problem for which many applications exist in biomechanics (e.g. blood flow in veins and arteries, flow of air in the bronchial airways).

Conclusion

It is necessary to understand that when the habit of sniffing, gasping and accelerating the air in breathing has been developed by a subject, the ‘simple geometrical solution’ of directing the Head forward and up relative to the torso should not be sufficient to promote good use of the breathing and vocal mechanism. Both habits of pulling the head back and of accelerating the air flow have to be dealt with in the reeducation.

The young Alexander solution to the irritation of the airways

First Part: The indirect geometrical solution

Owing to his deep knowledge of the Delsarte System, Alexander quickly “found out” that the geometrical arrangement of the head relative to the torso was the major cause of his throat trouble. More importantly, Alexander realised that the prevention of the tendency to put the head back could not result from a direct order, but had to be obtained by an indirect procedure involving a series of concerted instructions.

To explain the concept of the ‘indirect solution‘, I will demonstrate that the cause of the geometrical problem lies not in the neck use but in the coordination of the different parts of the “centric joint” as Delsarte called it, i.e. the articulated mechanism of the torso. The problem of the depressed larynx is obviously “in the neck”, but the solution lies elsewhere, in changing the geometry of the torso and neck.

Alexander does not say anything else in the “Use of the Self”:

The functioning of the organs of speech was influenced by my manner of using the whole torso, and that the pulling of the head back and down was not, as I had presumed, merely a misuse of the specific parts concerned, but one that was inseparably bound up with a misuse of other mechanisms which involved the act of shortening the stature. If this were so, it would clearly be useless to expect such improvement as I needed from merely preventing the wrong use of the head and neck. (Alexander, F., M., “The use of the self”, “Evolution of a Technique”, p. 9)

How are we to understand this declaration?

It is clear that when the top of the thoracic spine (top of the torso) is pulled back in space relatively to the middle part of the torso as if to perform the conception of a plumb-line figure with a straight neck (straight cervical spine) – certainly in a spontaneous reaction to the stimulus to ‘go up’ and to ‘lengthen the back’–, then the base of the cervical spine (the 1st thoracic vertebra just below the 7th cervical) is pushed too far back, irremediably pulling the cervical spine and the head back toward the middle line of the torso, constricting the airways into a smaller place.

In that plumb-line geometry of the torso, no amount of wishing for the head to go forward and up or to nod the head down will achieve anything useful in terms of the relationship between the head and torso which could open the airways and prevent the depression of the larynx because in this rigid coordination of the different parts of the torso, any attempt to put the head forward would put it down and compress even more the airways.

A well known Alexander technique website Dimon Institute illustrates Head Forward and Up with a plumb line skeleton.

Have a look at the picture used in the Dimon Institute Blog, a well known modern Alexander technique website in the US, to explain the meaning of “head forward and up”, from The Dimon Institute explanation of “Forward and Up”.

You will recognize instantly the “plumb line posture” (because the back of the head is aligned on the back line) and the fact that the back of the torso is neatly aligned, as if the skeleton had spend too much time lying down on a table top. I have added the grey lines to show the relationships between the middle and top of the back of the torso (1st thoracic vertebra pulled back) with the head and the angle of the sternum.

The model presents a straight cervical spine. Nothing seems to indicate that it is a medical condition (is it considered healthy?) and the solution proposed to get the head ‘forward’ lies only in the green arrow: according to Dimon, releasing the muscles of the back of the neck to nod is what ‘forward‘ means in the sentence “Head forward and up”, and the manner of using the whole torso is not considered at all.

See how the shoulder-blades are retracted toward the spine —the upper parts of the arm are not represented, but it is clear that the thorax where the lungs are situated is seen to be in front of the arms, instead of being, as it should be, behind them (Alexander, msi, p. 166). When the back is narrowing like this, the intense shortening of the major muscles linking the Head and the Shoulder-blades cannot but pull the head toward the back of the torso.

According to the Dimon Institute Blog, the “forward” position of the head, i.e. the nodding forward, is obtained by merely preventing the wrong use of the head and neck. You are told that, if you stop the tightening of the neck muscles (direct action), the head shall nod “Forward”. In the written explanation next to the image, the meaning of the word “forward” is clearly not linked with the manner of use of the mechanism of the torso:

In a general way, we know that “forward and up” of the head means that we don’t want to pull the head back and down. But why do we use these words, and what exactly do we mean by them–that is, what do we mean by the “forward” and what do we mean by the “up”?

>We’ve already seen that the skull sits on the atlas, or top vertebra of the spine, and nods at this point. This gives us an idea of what the “forward” refers to. Because we tighten the neck muscles and pull the head back, we have to stop this tightening to allow the head to nod forward at the AO joint between the ears, and put the extensors in the back of the neck on stretch; that’s the “forward”. (“The anatomy of Directing, Forward and Up“)

This proposition is clearly utterly different from Alexander’s statement indicating that it is the manner of use of the whole torso which affects the vocal organs and the pulling of the head back and down.

I admit that it is possible that the graphic artist working for the Dimon Institute may not have the knowledge to interpret the anatomical drawings presented. Yet, there is an unmistakable pattern: on a different article of the same blog, the “monkey position” presented is also portraying the retracted head of the plumb-line conception with a straight upper thoracic spine and a straight cervical spine.

When you compare the Dimon Institute representation of Monkey Dimon Institute: the anatomy of lengthening the front length with Alexander’s performed monkey, the difference is obvious: in Alexander’s photos, the placement of the neck is not caused by the neck itself, but below, by the new voluntary conformation of the main thoracic curve. The coordination of the torso is totally different.

You can look at all Alexander’s pictures. In his conscious use of the parts of the torso, the first thoracic vertebra is never aligned with the back line; the head is therefore very far forward from the “place of the back” he was referring to in the Bedford Lectures in 1934.

This explains why Alexander insists in remarking that “merely preventing the wrong use of the head and neck” is useless.

Alexander’s first thoracic vertebra is always forward of the back line. His torso is clearly articulated with a different principle than the ‘plumb-line’.

In order for the spot “Ear” (green) to be so near the vertical line of the spot “throat” (red), the top of the torso cannot be aligned on the back of the torso.

It is only by reeducating the direction of the use of the different parts of the torso that the spine as a whole can allow the cervical spine and the head to be in the ‘position’ [relationship to the torso] which Alexander used to impose with his hands on the body of his pupils to free their airways and neck.

On this picture, next to the diagram showing the opening of the upper airways as a result of the new organization of the top of the torso (base of the neck) in relation with the lower back line, it is clear that Alexander is manipulating the pupil in order to achieve what he is doing with the different parts of his own torso.

On this particular subject, Alexander never wavered in all his books and established the concept of the indirect solution as a central principle.

If there is any undue muscular pull in any part of the neck, it is almost certain to be due to the defective co-ordination in the use of the muscles of the spine, back, and torso generally, the correction of which means the eradication of the real cause of the trouble.

This principle applies to the attempted eradication of all defects or imperfect uses of the mental and physical mechanisms in all the acts of daily life and in such games as cricket, football, billiards, baseball, golf, etc., and in the physical manipulation of the piano, violin, harp, and all such instruments. (Alexander, F.M., “Man’s supreme inheritance“, Chaterson Ltd 1910, reprinted 1946, p. 127)

In another article which I will publish shortly (“What do I see“), I proposed a complete analysis of a few Alexander portraits taken while he was manipulating pupils: it is clear that he was ‘shaping’ his pupils to obtain the same form of the torso as the one he obtained by following his conscious and indirect model, this same form which would propel the head forward and up without any direct intervention.

Alexander was also certainly pulling (gently) their head forward “in place”, but, had he be more patient, he would have noticed, as I did, that by just changing his/her direction of the mechanism of the torso, a pupil will unknowingly bring the head in the relationship with the torso shown below by Alexander.

I instruct every teacher having Skype lessons with me on how to create that experiment for themselves and for their pupils. As every lesson is taped for future work and conscious control, the teacher gets a visual demonstration that by consciously directing the movements of the different parts of the mechanism of the torso (without ever directing the head), the head is moved indirectly to a new ‘position’ relatively to the lower part of the back.

When you know all this, you cannot look at pictures of the modern conception of the Head relation to the torso in the same way. The time of Alexander is now long past and it is interesting to contrast Alexander’s use of the parts of the torso, neck and head with the one of his distant relatives: the modern Alexander teachers.

The internet is full of pictures of Teachers of the modern Alexander technique and it is clear that their conception of the movements of the parts of the torso is now totally different from the one which guided the old teacher, when he was working with himself as well as when he was working with someone else.

Just look at the relationship between the top of the back of the torso and the neck and you will see the conception of the plumb-line monstrosity (as Alexander used to call it), with a straight cervical spine, a mechanically depressed larynx and, as we will see later, a restricted mean thoracic capacity.

Are these modern teachers not supposed to feel (embodied cognition) what is right for their pupil? Are they not deep in contact with mindfulness, drinking at the source of the natural poise in the here and now?

The head-forward-and-up technique has become the straight-neck-back technique. The direct line of transmission embodied in touch seems clearly at fault, especially when you understand the reasoning behind the original or initial idea of the relation between use and functioning.

A rational use of the torso projects the head forward and up from the back to open the airways

On this photo of Alexander giving a lesson in 1932 (I have hidden the pupil to focus the attention on Alexander’s form), it is for all to see that the relative position of the head to the back cannot be spontaneous, especially because we know beyond doubt that this man had a strong sensorimotor habit to pull the head back relatively to the torso.

It is also clear that the head is forward from the back of the torso, not by a direction of the neck in relation to the head alone, but because the thoracic cavity (in the torso) is ‘respected‘ and not unnaturally straightened by pulling the top of the torso back in an attempt to lift the front of the chest up.

I have added a blue dot on the spinous process of the first thoracic vertebrae to show clearly that this use of the mechanism of the torso is completely different from the ‘plumb line conception’ of going up in which the 8th vertebrae (orange dot on the diagram) and the 1st are on the same line.

See how far the top of the back of the torso is from the line of the lower part of the back of the torso. It is only because the first thoracic vertebra is projected forward that:

- the head can be so far forward without being pulled down, and,

- the sternum is not inclined backward at the top, but clearly parallel to the front of the torso.

The geometry of the back and the relationship with the head is striking and cannot be mistaken with the flat table back of the modern plumb line skeleton.

As everyone knows, the thoracic curve of the spine belongs to the torso: as this curve is fundamental to obtain the new relationship between the head and torso contributive to an opening of the airways and a correct suspension of the larynx, then the functioning of the organs of speech is really influenced by the manner of use of the mechanism of the torso and certainly not by any direct non-effort to free the neck.

On this picture, there are two fundamental points:

- the first thoracic vertebra is very far forward from the line of the lower back or back-line (this is certainly the origin of the expression/order “let the back back“);

- the first vertebrae in contact with this ‘back line’ (the orange line which shows how Alexander is directing the lower part of the torso) is the 8th one (and certainly not the first thoracic at the top of the torso as in the plumb-line skeleton).

As a consequence of this adjustment, the front of the torso presents a very unusual, straight shape and not the rounded shape that is so prevalent nowadays with the sternum pointing forward at its lowest extremity (first image on the left below). Alexander is displaying a geometry of the torso such that the sternum line is aligned with the front of the 8th rib (frontal plane of the torso) and the anterior superior iliac crest (Iliac).

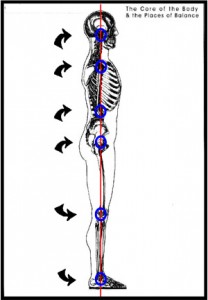

This is a “block analysis” of the plumb line skeleton versus Alexander’s conscious use of the mechanism of the torso.

Articulating the top of the torso in a new relation to the other parts of the torso is the only way to comply with the old Delsarte’s instruction to align the ear, throat, upper part of the arm, front of the ribs and front of the pelvis to present an “active chest”. In these conditions, it is clear that the head is forward and up relatively to the back line of the lower torso.

As I have already pointed out, this in turn implies that the sagittal line of the sternum is not inclined relatively to but parallel with the front of the torso.

I have every reasons to believe that this organisation of the four parts of the torso was called “position of mechanical advantage” by the young Alexander. As I have explained elsewhere, it is not a “position” but a geometry, i.e. a set of relationships between different bony structures of the torso which can only be attained by a concerted series of movements (the means-whereby lengthening and widening the back) and which can be adapted to almost any gesture provided the movements of the different parts of the torso are consciously coordinated to maintain the “shape” in motion.

The position of the shoulder-blades is easy to define, because the upper-parts of the arms are forward of the rib-cage as requested by Alexander (Alexander, msi, 1945 ed., p. 166): this is the means-whereby the upper back is widened. I point this obvious fact to the reader to remind him/her to the fact that most of the written comments on geometric adjustments Alexander has made in his books can be experimented upon and falsified when necessary (it is not the case here).

Lengthening the spine is not obtained by trying to achieve directly a “straight-back torso and neck”: aligning the whole back of the torso on a door side or on a table cannot be an expression of what Alexander meant by lengthening the back with “good use”. The “lengthening and straightening of the back” has to be determined in function of the prevention of the depression of the Larynx.

Second Part: Lengthening to increase the mean thoracic capacity

Alexander’s explanation of his solution is a reminder that the breathing mechanism is dependent on the global direction of the practical will:

Now in dealing with this case, many parts of the organism will require readjustment. The spine must be straightened and lengthened, the mean thoracic capacity permanently increased in order to give free play to the internal organs, and the firmly established habit of drawing breath by sucking air into the lungs must be broken. (Alexander, F.M., “Man’s supreme inheritance”, Chaterson Ltd 1910, reprinted 1946, p. 122, «The Processes of Conscious Guidance and Control»)

Too little attention has been given to the series of criteria of good use prescribed by Alexander. The concept of “straightening the spine” has completely overshadowed the other linked concepts of “preventing the depression of the larynx” and of “increasing permanently the mean thoracic capacity“. The one-track brain has led the conception of the use of the self toward a plumb-line or table straight line. If our teachers had studied Alexander’s written explanations with a mind keen on experimenting, i.e. without fear of “end-gaining”, they certainly would have realized how each criteria limits and specify all other criteria of good general use of the self.

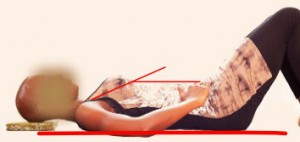

Therefore, when reading the quote above, it is important to exert discrimination regarding the adjective “straightened”. “Straightened” should not be taken literally: I sometimes see teachers gently pressing the top of the torso and the shoulders of their pupils on a table. I will now use this same quote to demonstrate that “Straightening the pupil as a table top” should be recognised as BAD USE because it does not only depress the upper airways (see previous chapter), but it also severely diminish the mean thoracic capacity!

In support to this terrible allegation against lying down on a table top, I will put forward three arguments (I have added the photographs of Alexander because I was afraid that some who dislike Alexander would think he represents a special case and that his way of using himself is not a model of the result he described as back to lengthen and widen and head forward and up):

- As a first visual argument, I already presented 9 photographs of the master teacher, from whose it must be clear to anyone-who-can-see, that “straightening” the thoracic spine did not mean in his idea and cannot mean flattening the thoracic curve and pulling back the top of the torso on the back line, and,

- second, I will show that, to comply with the second rule of adjustment advocated by Alexander, i.e. the mean thoracic capacity must be permanently increased, we should stop pulling the top of the chest up and back,

- Third, the reason that so many teachers are advocating a Plumb Line model could be that they are in fact conceiving the Table-top idea of lengthening the back as an ideal of upright coordination: the two models are so similar that it is possible that they did not see the trap.

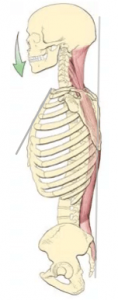

In order to permanently increase the mean thoracic capacity, or vital capacity, defined as the maximum amount of air a person can expel from the lungs, there is only one way to “straighten” the torso : the upper thoracic curve must be respected when coordinating the movements of the parts of the torso. Lengthening must be obtained, but without lifting the chest UP and Back.

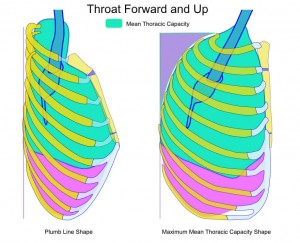

Modeling the mean thoracic capacity gives a correct indication of the proper lengthening of the back.

The diagram on the left shows the habitual plumb-line ribcage (or if you view it flat and not vertical, you see the ribcage of a human lying down on a table): the top of the back of the torso is on the same line as the back of the lower part of the torso, the sternum is down (first rib going down) and is inclined backward at the top. The mid-ribs are flaring forward and the upper half of the ribcage is less than the other half.

As a direct result, in the plumb line diagram (on the left), the front of the chest is lifted back but the sternum is not lifted at all: the lungs are compressed by the collapse of the front of the ribcage, thereby reducing the mean thoracic capacity to a minimum.

The second drawing (on the right) is a replica of the ribcage displayed by Alexander’s shape of the torso when seen working with the little girl. The back of the first rib is very far forward from the back line and the front of that same rib is very far away (up) from the front of the pelvis: the sternum is lifted Forward and Up and all the inter-costal muscles are lengthened. The sternum is not bended anymore and is vertical. Behind, at the top of the back of the torso, the purple triangle is a reminder of the curved shape Alexander is presenting in all his pictures.

I have represented the ‘hilum of the lungs‘ where the trachea (the airway tube) is connecting with the lungs. It is then possible to see the angle “forward and up” of a free trachea.

Remember that the lung are attached on all sides to the ribcage via the pleura. It is not difficult to estimate which of the two diagrams represents the maximum increase of the mean thoracic capacity: can anyone doubt that the general capacity of the bag is a sure sign of the standard of efficiency? Alexander introduced this same demonstration in his first book:

Let us, for a moment, think of the thoracic and abdominal cavities as one fairly stiff oblong rubber bag filled with different parts of a working machine which are interrelated and interdependent, and which are held in position by their attachment to the different parts of the inner surface of this bag. We will then suppose, for the sake of our illustration, that the circumference of the inner upper half of this bag is three inches more than that of the lower half. As long as this general capacity of the bag is maintained the working standard of efficiency of the machinery is indicated as the maximum.

Let us then, in our mind’s eye, decrease the capacity of the upper part of the bag and increase that of the lower half until the inner circumference of the latter is three inches more than the former. We can at once picture the effect on the whole of the vital organs therein contained, their general disorganization, the harmful irritation caused by undue compression, the interference with the natural movement of the blood, of the lymph, and of the fluids contained in the organs of digestion and elimination. In fact we find a condition of stagnation, fermentation, etc., causing the manufacture of poisons which more or less clog the mental and physical organism, and which constitutes a process of slow poisoning. (Alexander, F.M., “Man’s supreme inheritance“, Chaterson Ltd 1910, reprinted 1946, p. 11)

Therefore, the idea of lengthening the whole back of the torso and head on a door side or a table top is certainly not promoting good use, but a general disorganization. Lying down has never promoted an ‘active chest‘ as it is an attitude in which the standard of functioning is closer to sleeping than any other human activity.

When Alexander was working on a pupil, imposing his guidance with his hands, as on the image below, it is clear that he was always coordinating the movement of the head forward with the increasing of the mean thoracic capacity, bringing the sternum more and more vertical by guiding the first thoracic vertebra forward (I call this “respecting the upper thoracic curve”) of the line of the lower back.

Alexander working on the upper part of the back of the torso to change the habit of pulling the upper chest back.

Alexander is working to bring her head more forward-and-up relatively to the back line of the lower torso by guiding her torso in a more extended position of the top part of the back in relation to the lower part of the back.

I look at the shape of his right hand on the upper part of the torso of the pupil: he is expanding the horizontal distance between his little finger and his thumb, thereby re-arranging the top of the torso in relation with the back line to increase the thoracic upper curve.

With his right hand, Alexander is clearly working to increase the curve of the top of the torso in order to give the pupil the maximum mean thoracic capacity and also to help open the thoracic curve to project the head forward and up and, indirectly, prevent the depression of the larynx.

With his left hand, he is just maintaining the cervical spine in connexion with the angle of the upper thoracic curve. It is not this left hand which is creating the movement of the head forward and up: the movement comes from the new coordination of the parts of the torso.

As far as I can see, this pupil is still pulling her chest up and back: her Ear is still a long way behind the vertical line of her Throat (top of the sternum) and she has the stiff cervical line indicating that her neck is not free.

The instruction “back back” did not mean straightening the top of the torso, i.e. “pulling the top of the chest back” as some do when they want to “look Alexandroid” (there is no resemblance between Alexander directing his torso and the Alexandroid form). Pull the back back can be understood when one remembers the Bedford Lecture (see J.O. Fisher, “Articles and Lectures”, p. 177) where Alexander explains:

She is directing her head forward and up from here (Alexander indicates with his hands a part of her back), he knees forward and the hips back, and that the only way you can get your antagonistic pulls.

This is not a quote dating from the early texts: it is posterior to the opening of the first training course.

A little bit of controversy

“You only escape ambiguity at your own expense” (Cardinal de Retz, 1613-1679, quoted in “Mémoires du Cardinal de Retz, de Guy Joli et de la duchesse de Nemours”, ed. 1820).

As a consequence of the deductions presented in this paper, i.e. that it was fundamental that the first vertebrae should not be aligned with the back of the torso to achieve the “head forward and up result”, as soon as the year 2000, I started to explain [in a STAT meeting in France] that prescribing lying down on a table should be abandoned because it encourages a kinaesthetic imprinting of a wrong use of the mechanism of the torso and as surely, it prevents the students from ever finding out by reasoning what were the connected end-results (“Head forward and up”, “Free Larynx” and “Maximum mean thoracic capacity”) of the means-whereby instructions as exemplified by Alexander self-practice in action.

I let you imagine what could be the reaction of the tradition-bound society of teachers of the modern Alexander technique! (this explains why you haven’t heard of me for the last 15 years). After fifteen years, some Alexander teachers still turn their head away in order not to salute me! And imagine that at the time, I was still manipulating the pupils in the modern Alexander way. Many senior teachers who do not know anything of my work call me a “charlatan” just because I teach the Alexander technique over Skype: if they knew that I have not taught semi-supine for fifteen years, they would certainly find the word too sweet.

For fifteen years, I have kept these ideas for myself and I never taught the lying (untrue) semi-supine again. My lessons are all exactly sixty minutes, and the pupil (teacher or not) is only involved in experimenting with his conscious guidance of the movements of his torso in relation with the limbs (neck, arms, legs), without a minute to spare.

Look at a picture of Alexander directing his use of the torso in the best of conditions (this occurs apparently every time he his manipulating a pupil) and see how far he consciously directs the top of the torso forward from the middle of the torso, thereby expanding the thoracic capacity (I explain this in great details in the article “What do I see”) and indirectly projecting his head forward, just above his sternum and front of the torso. Any other way to “put the head forward” would put it “down”.

His sternum is NOT projected back at its upper extremity: would Delsarte place one of his wooden ruler on this sternum, it would be vertical in standing at ease!

Now examine this image from the Stat Website: