to download this article as a PDF: https://www.dropbox.com/s/tlzs0j0ov12las1/You%20asked%20me%20to%20practice%20pulling%20the%20belly%20in%20while%20inhaling%20even%20though%20FM%20says%20not%20to%20do%20this%E2%80%A6%C2%A720200227154608.pdf?dl=0

Could you provide the excerpt where F.M. Alexander writes about not increasing the abdominal pressure or about not drawing the abdomen in while inhaling? I have found no evidence whatsoever about such interdiction. In your question you say that F.M. Alexander said not to do this and I need to know the exact source of your knowledge. I am deeply interested in listing all the contradictions or theoretical tensions which can be found in his writings.

I will show you that, while it may be possible that you have found an instance in which F.M. Alexander has indeed declared that drawing the belly in should be inhibited in inhalation (to tell the truth I really disbelieve it because he kept pointing to the fact that all his pupils were doing the exact opposite), he seems to have had a clear, unwavering understanding of what was incorrect in the breathing movements, that is, when some breathing movements interfered with the correct torso movements.

His point of view which I will expand is surprisingly close to that of François Delsarte. The latter made no mystery that he was totally impressed by the Bel Canto teachings which advocated abdomen-in action during inhalation and that he had regained the use of his voice through procedures directly inspired by the Bel Canto teaching regarding breathing and voice production.

First, let me remind you that the inhalatory behavior cannot be exhaustively described simply as belly-in or belly-out. In practice, I did not ask you to restrict the new inhalatory behaviour to belly-action, but to organise and concert the movements of the lower middle and upper torso at the same time as increasing the action of the anterior abdominal wall. Now that this clarification is out of our way, let’s start with the question of the undue abdominal pressure of which F.M. Alexander is making the center of his technique of re-education.

The contentious question of undue abdominal pressure

I need to point out a curious problem of translation that I have seen very often in the dominant teaching of the modern Alexander technique. Very often, I have heard modern AT teachers saying that the pupil should let go of “undue abdominal pressure” that they tend to cause by trying to obtain a very decided improvement in the figure (see Alexander, F.M.; msi, p. 232) through giving consent to the unique order of “sucking the belly in”. In other words, it is contended that many adults are trying to flatten their abdomen by a direct attempt at drawing the belly in (notwithstanding the absolute ineffectiveness of the cure) and that they should stop doing the “wrong thing”.

The confusion is absolutely complete. While it is correct that obeying one isolated order (“suck the belly in”) is “end-gaining”, that is “doing the wrong thing” (trying to obtain a focal result without directing the concerted movements of all the parts of the torso), it is absolutely incorrect to instill the idea of releasing the abdomen out (or allowing for a drawing-out of the abdomen) in the inhalatory sequence. The real reason for the foolisness of the advice is that F.M. Alexander was not associating “undue abdominal pressure” with too high a pressure in the abdomen but, on the contrary, to weak, insufficient and depleted intra-abdominal pressure. This is not an opinion of mine and I will demonstrate in detail how F.M. Alexander expanded on this theory.

If “undue abdominal pressure” was excessive internal pressure, why would F.M. Alexander recommend to combat the “harmful flaccidity of the abdominal muscles”? You must realise that in all logic, any strengthening of the abdominal muscles, as well as any direct action toward a reduction of the protruding abdomen is going to increase the abdominal pressure and not lower it. If he considered that the adominal pressure is too high in a person with a protruding abdomen, why would he insist on having the pupil reduce the harmful flaccidity of the abdominal wall?

There is an undue intra-abdominal pressure and harmful flaccidity of the abdominal muscles

In F.M. Alexander’s books, the adjective undue means “incorrect” and not, as it is often alleged by the somatic advocates of unconditional (unreasoned) release, “excessive”. In order to ascertain what is ‘incorrect’ in the pressure, it is recommended to reason things out, that is to link the adjective with the context developed in the passage by the author.

To judge the point, consider that F.M. Alexander condemns the use of bandage and corset to prevent a lack of intra-abdominal pressure not because the goal is wrong but for the simple reason that it tends to make the abdominal muscles more flaccid than they already are (see quote below, Alexander, F.M.; msi, p. 232), when they should supply the support required. To make the point clear, at the same time, he says that re-education is a strenghtening of the support Nature has supplied: he clearly encourages the development of the abdominal muscles as a part of a concerted, reasoned attempt at changing the habitual conditions of use and, as I have already pointed out, he is clearly advocating augmenting the internal abdominal pressure by the adoption of practical means to remove the cause.

“From the first lesson the effect upon the splanchnic area is such that the blood is more or less drawn away from it to the lungs, and is then evenly distributed to other parts of the body. The intra-abdominal pressure is more or less raised, and there is a gradual tendency to the permanent establishment of normal conditions.

The use of bandages or corsets is to be condemned as treatment in protruding abdomen instead of the adoption of practical means to remove the cause. Such support to the abdominal wall is artificial and harmful, since it tends to make the muscles more flaccid. The respiratory mechanism should be re-educated, for this would mean a re-education or strengthening of the supports Nature has supplied. In other words, the sinking above and below the clavicles and the undue hollowing of the lumbar spine —the great factors in the direct causation of the protrusion of the abdomen—are removed, and a normal condition of the abdominal muscles established. This means a very decided improvement in the figure and general health.

The improvement in the abdominal conditions (improved position of the abdominal viscera and the development of the abdominal muscles) is proportionate to that of the respiratory movements—a fact that can be readily understood when I point out that the movements of the parts are interdependent.

When the faulty distension of the splanchnic area is present it will be found that the diaphragm is unduly low in breathing ; and when there is excessive depression of the diaphragm in respiration there is interference with the centre of gravity by displacement forward, and the compensatory arching backward in the lumbar region.

(Alexander, F.M.; Man’s supreme inheritance, (Second Ed. Revised, 1918), p. 232).

-

the lengthening and backward movement of the abdominal wall (improvement of the abdominal conditions) to reduce the volume of the abdominal cavity in such a way that the blood is more or less drawn away from it to the lungs.

-

the intra-abdominal pressure is raised, and,

-

that the respiratory movements should be changed when they interfere with this organisation of the different circumferences of the torso.

Re-education of the respiratory strategy to strengthen the abdominal wall

When F.M. Alexander says that the respiratory mechanism should be re-educated, he means a re-education or STRENGTHENING of the abdominal wall by a “DEVELOPMENT of the abdominal muscles“. Do you think that your partly subconscious habit of letting the belly go out in breathing-in will tend to ensure a strengthening of the abdominal wall and a development of the abdominal muscles?

F.M. Alexander writes that the improved position of the abdominal viscera (obtained by stopping to pull the front of the pelvis down towards the knees in standing) and the development of the abdominal muscles is proportionate to that of the respiratory movements. I have found that many students who start to be able to coordinate a correct movement of the pelvis relatively to the legs and various movements leading to the extension of the upper torso away from the lower torso (exactly like what you have been projecting in your lesson with me) do not progress how they should because they are impaired by their breathing habit of releasing the abdominal muscles when breathing in. Each time they are asked to think about breathing and particularly breathing in, they subconsciously release the abdominal wall and their general use tends immediately to revert to their old bad habits.

But before I go into details to explain the reason why it is important that you experiment in this direction, it is primary that you realise how crucial is the notion of interdependence of the movements of the parts. For F.M. Alexander, the undue intra-abdominal pressure goes hand-in-hand

-

with an harmful flaccidity of the abdominal muscles IN REST,

-

with the usual shortening of the stature (and interference with the center of gravity),

-

with the protruding abdominal wall,

-

with the unduly low position of the diaphragm in breathing-in, and

-

with the habit of inspiratory coordination of the movements.

We are not discussing independent movements which can be worked upon in isolation. For example, pulling the abdominal wall backward, pulling the upper torso away from the pelvis (an action which lengthen the abdominal wall) or pulling the Sitting-Bones spots forward toward the thighs are never to be considered independently. Doing any of these action in isolation is “End-gaining” and should clearly be inhibited.

We are not discussing independent volumes either. I already directed your attention toward F.M. Alexander’s conception of the torso as an oblong rubber bag connecting two cavities (abdominal and thoracic) and toward the “two circumferences rule of general functioning” that he explained in the first pages of his first book. F.M. Alexander’s model is clearly based on the principle of communicating volumes. What this means is that, for F.M. Alexander, the expansion of the upper torso is inversely proportional with the expansion of the abdominal (splanchnic) area. The more one subject is expanding the lower rib-cage and releasing the abdomen out in breathing-in, the less is it possible to expand the thoracic region in the upper and middle part of the torso.

“Let us, for a moment, think of the thoracic and abdominal cavities as one fairly stiff oblong rubber bag. We will then suppose, that the circumference of the inner upper half of this bag is three inches more than that of the lower half. As long as this general capacity of the bag is maintained the working standard of efficiency of the machinery is indicated as the maximum.

Let us then, in our mind’s eye, decrease the capacity of the upper part of the bag and increase that of the lower half until the inner circumference of the latter is three inches more than the former. We can at once picture the effect on the whole of the vital organs therein contained, their general disorganization, the harmful irritation caused by undue compression, the interference with the natural movement of the blood, of the lymph, and of the fluids contained in the organs of digestion and elimination. In fact we find a condition of stagnation, fermentation, etc., causing the manufacture of poisons which more or less clog the mental and physical organism, and which constitutes a process of slow poisoning.

(Alexander, F.M.; Man’s supreme inheritance, Chaterson Ltd 1910, reprinted 1946, p. 11)

Pulling the belly back, narrowing the distance between the Rib-8 spots, lengthening the upper torso away from the lower torso are all instructions intended

-

to reduce the capacity (volume) of the lower part (abdominal or splanchnic), and,

-

to give a chance to the new action of expanding the capacity of the upper bag.

It would be very surprising and illogical to imagine that in breathing, in the inhalatory strategy, we should go for the habitual, conventional release and expansion of the capacity of the lower part of the bag for the simple reason that it goes against the logic of the model F.M. Alexander describes. I maintain that the harmful flaccidity of the abdominal muscles must be reeducated and the addominal muscles strengthened at the very moment we are taking an in-breath.

Many readers have complained about F.M. Alexander detailed and at the same time “inefficient descriptions”. When F.M. Alexander is describing “psycho-mechanical defects”, I rather find his description quite efficient and consistent:

(3) The marked lumbar curve of the spine with the usual shortening of stature and protruding abdominal wall. Harmful flaccidity of the abdominal muscles and general stagnation of the abdominal viscera.

(Alexander, F.M.; Man’s supreme inheritance, (Second Ed. Revised, 1918).pdf, p. 179)

Inhalatory strategy or Postural changes related to it?

When F.M. Alexander recommends IN WRITING to control directly the muscles of the abdominal wall in order to reduce a protruding abdomen, nowhere does he indicate that we should restrict this strategy to breathing-out. Nothing indicates that you should not experiment with the abdomen-In action during inhalation as, for F.M. Alexander, it is the organisation of the movements of the different parts of the torso which is primary in order to expand the thoracic capacity and contract the abdominal cavity. In other words, if your habit associated with breathing-in involves a subconscious, automatic release of the abdominal muscles that feels “RIGHT”, you should reconsider your habit and explore what would happen if you were to change your sensory appreciation that is associated with this habit.

we can control directly the muscles of the abdominal wall which encloses the viscera, and in reducing a protruding abdomen we can control many other muscles, notably those of the back

The “pinched position of the stomach” which F.M. Alexander refers to is not caused by an excessive action of the abdominal wall, but by the different concerted movements that the subject is consenting to (that she is doing) with the lower, middle and upper torso and with the abdominal wall, especially when taking a deep breath.

I found interesting to investigate whether it was possible to take a very deep breath while preventing all the defects mentioned by F.M. Alexander. You are going to be surprised: it is not taking a deep breath that cause a problem, it is the poor activity of the abdominal muscles, the expansion of the abdominal area, the collapse of the lower back, the lack of capacity to lengthen and widen the back, ALTOGETHER. I know that due to your training in the modern Alexander technique this possibility may seem totally far-flung, but what do you risk in the attempt at concerting these movements consciously?

In the following passage, you will see that F.M. Alexander considers effectively that the conscious use of the different movements of the parts of the torso is primary. I translates his point of view as a primacy or superiority of the “postural rule” over the “respiratory habit”, because he states that, for him, the breathing movements are “not even secondary“. The respiratory movements represent for him a subordinate operation to the organisation of the movements of the different parts of the mechanism of the torso. Therefore, it should be conceivable to imagine subordinating the inhalatory sequence to the proper organisation of the movements of the parts —instead of the compulsory reverse strategy decreed by our habitual sensory appreciation. This is what the procedure I proposed is aming to.

Why should the breathing movement (inhalatory) NOT be associated with a release of the abdominal wall (protruding abdomen) and an undue [wrongly low] abdominal pressure?

For F.M. Alexander, the maximum intra-thoracic capacity is associated with “the normal and necessary abdominal pressure in the right direction“. It seems to me that these terms certainly do not indicate an idea of releasing the abdomen out during inhalation.

I will show that the right direction for the necessary abdominal pressure is BACK because the support for the poise of the chest rests on the correct actions of the back tissues which are directly controlled by the action of the abdominal muscles.

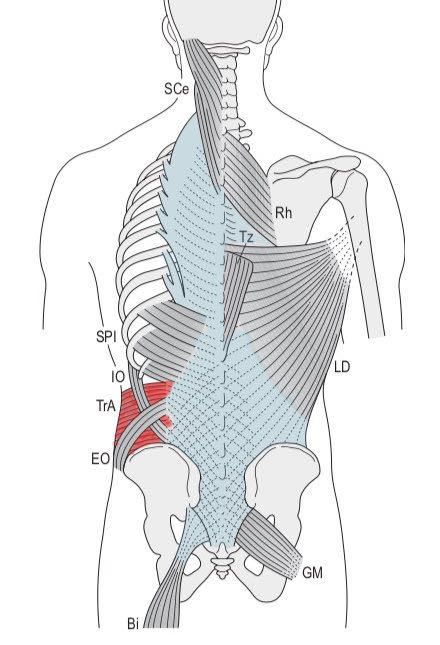

and that the tension developed in the fascia is controlled by the abdominal muscles that arise from it

What Gracovetky postulated, we can experiment in practice and establish in activity. All that is required is to readjust the movements of the parts irrespective of the fact that it feels difficult and wrong.

The giant fascia of the back connects all the vertebrae together as well as the main muscles of the back. Two rules are worthy of consideration:

-

this fiber reinforced structure can only provide elastic resistance when stretched,

-

due to the bi-directionality of the thoracolumbar fibres (look how the dotted lines representing the different connective bands of elastic material cross in the thoracolumbar region), it is possible to strengthen and “control” the lengthening resistance manifold by widening the fascia. This widening is caused by the Action of the TrA (transverse abdominis and internal oblique) which will pull the abdominal wall back.

This arrangement of the parts and connective tissues explains why it is so important to WIDEN the back to maintain the necessary lengthening and also it gives a new light to F.M. Alexander’s commentary that “in actively reducing a protruding abdomen we can control many other muscles, notably those of the back“.

I know my answer is desesperately long and fastidious, but I cannot suppress the need to give you important bio-mechanical clues which are going, one day or another, to illuminate your understanding of the general coordination that F.M. Alexander discovered for himself. This passage from Vleeming is crucial to understand the reason we strive to widen the back by drawing the abdomen in.

Stability and mobility are opposing states in joints. To stabilize the lumbar spine, especially between L1 and L4 levels without ribs, the transverse abdominis and internal oblique muscles and their fascial aponeurosis resemble a flexible myofascial ring between the thorax and pelvis. This ring runs posteriorly from the transverse abdominus and internal oblique muscles, to the CTrA (common tendon of the transversus abdominis and internal oblique) and via the MLF (Middle Layer of ThoracoLumbar fascia) connecting to the transverse process, mimicking a dorsal rib construction.

Anteriorly, the abdominal muscles fuse with the rectus abdominis fascia. The rectus muscle itself represents a contractible version of the inert bony sternum of the thorax or symphysis of the pelvis.

Posteriorly, the PLF (posterior layer of the thoracolumbar fascia) girdles the lumbar erector spinae and multifidus muscles.

This axial abdominal–lumbar myofascial ring, between the thorax and pelvis, generates muscles contraction to compensate for the lack of rib stability. In essence, tension in this myofascial can be adjusted by altering PMC pressure (PMC [paraspinal muscular compartment created by the ThoracoLumbar fascia]). The present study has demonstrated that co-contraction of the paraspinal muscles and the deep abdominal muscles is capable of creating this girdling effect.

(Vleeming, A.; The functional coupling of the deep abdominal and paraspinal muscles, 2014, p. 14)

If the torso is arched back during the inhalatory sequence —as a consequence of a weakening of the back support caused by a release of the abdominal wall— the thoracic elasticity and maximum intra-thoracic capacity are immediately jeopardised and nothing can help maintain the thoraco-lumbar unity but an excessive use of locomotion muscles which are not dedicated to that role.

On the other hand, when a position of mechanical advantage —that is a forward position of the upper torso and a backward position of the middle and lower torso— has been attained, the passive elastic structures of the back can

-

suspend the thorax (the forward cantilever of the upper torso maintaining the stretch and elastic resistance of the giant thoracolumbar fascia),

-

increase the distance between the thorax and the pelvis (stetching the elastic components of the abdominal wall) and

-

allow for a normal action of the abdominal muscles during the inspiratory movement (the lengthening of the back seen in F.M. Alexander means that the thoracolumbar fascia will inevitably narrow and absorb any slack in the transverse abdominis and internal oblique tendons, therefore providing a firmer base for their action of drawing the abdomen in.

This axial abdominal–lumbar myofascial ring, between the thorax and pelvis, generates muscles contraction to compensate for the lack of rib stability. In essence, tension in this myofascial can be adjusted by altering PMC pressure (PMC [paraspinal muscular compartment created by the ThoracoLumbar fascia]). The present study has demonstrated that co-contraction of the paraspinal muscles and the deep abdominal muscles is capable of creating this girdling effect. (Vleeming, A.; (2014) The functional coupling of the deep abdominal and paraspinal muscles, p. 14)

During the practical process by which the thoracic elasticity and maximum intra-thoracic capacity are gradually established, the body of the subject is at the same time readjusted, and mental principles are inculcated which will enable him to maintain the improved conditions in posture and co-ordination which are being set up, and which will secure the normal and necessary abdominal pressure in the right direction, thus constituting a natural form of massage of the digestive organs which is maintained during the ordinary actions of everyday life.

(Alexander, F.M.; Man’s supreme inheritance, Chaterson Ltd 1910, reprinted 1946, p. 115)

securing the normal and necessary abdominal pressure in the right direction

Is there any evidence supporting F.M. Alexander’s point of view?

In a paper published in 2001 (Journal of Voice, Vol. 15, No 3) , Jenny Iwarsson has shown inadvertently that F.M. Alexander may have been right, i.e. that the strategy abdomen-in in inhalation has more to do with preventing unwanted postural changes (narrowing and shortening the back and all the other associated defects) than with restricting space for the descent of the diaphragm or establishing improved vocal conditions.

We know that when the transverse abdominis and internal oblique are brought into play (abdomen-In condition), the thoraco-lumbar fascia to which they are linked is widened, directly increasing the elastic resistance of the fascia of the back from the head to the pelvis and stretching the encased muscles.

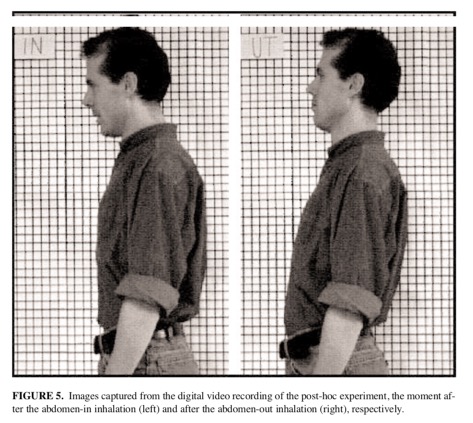

What the images below are showing is that when a singer is required to pull the abdomen in (left) during the inspiratory sequence, the most obvious consequence is a change in the postural reaction as a whole (and not as most singing experts tend to say, in a change in the LV —lung volume). The decision of drawing the abdomen in inhibits a reaction that the subject does not register, that is the pulling of the upper torso backward, the sinking above and below the clavicule, the shortening and narrowing of the back, the depression of the diaphragm, and the incorrect poise of the chest (as seen on the right image). On the right, the same singer is filmed during an other attempt at breathing-in, but this time, he is instructed to draw the abdoment out. You can be certain that he is totally unaware of the concerted movements of the different parts of the torso which happen in consequence of the one order that he has received and given consent to put into practice.

“The results confirmed that the two inhalation patterns affected body posture in all these subjects. The abdomen-out condition was associated with a posture characterized by either a slightly posterior tilt of the head (right part of Figure 5), or a protrusion of the chin (not seen in the subject in this picture). Both these gestures would induce a rise of the VLP as measured by EGG. The abdomen-in condition seemed associated with an expansion of the rib cage and a recession of the chin toward the neck (left part of Figure 5). The vertical distance between the mental protuberance of the chin and the reference point was found to be longer in the abdomen-out condition than in the abdomen-in condition for all 6 subjects. (Iwarsson, J.; Effect of inhalatory abdominal wall movement on vertical laryngeal position during phonation, 2001, Journal of Voice, Vol. 15, No. 3, 2001, p. 390)

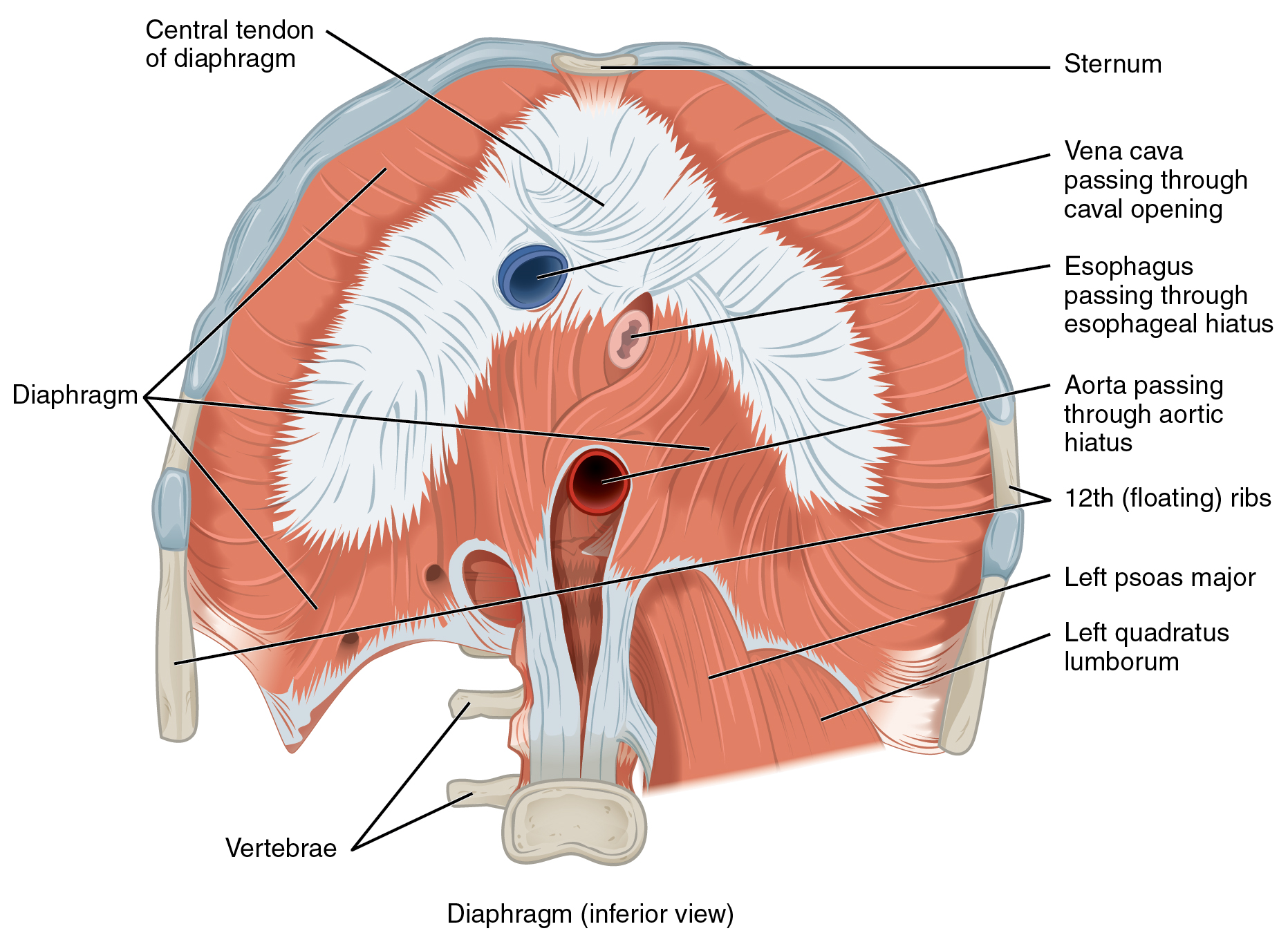

Note that the distance (depth as seen from the sagittal view) between the lower part of the sternum and the lumbar region is maximum when the back goes back and the upper torso stays forward (abdomen-in image on the left): these locations are the origin and insertion of the diaphragm (going as low as the third lumbar vertebra). Iwarsson’s photograph on the right shows that the belly-out inhalatory technique results in the poorest conditions of use of the diaphragm system that F.M. Alexander calls “depressing the diaphragm“. The diaphragm is depressed for two reasons:

-

the working length of the diaphragm is too short in the abdomen-out condition,

-

the abdominal content is sinking forward and not opposing the downward movement of the diaphragm, thereby preventing the expansion of the sides of the ribs.

Let me explain why it is necessary to maintain the length of the diaphragm when it is contracting (during the breathing-In phase) by observing the diaphragm from beneath.

Obviously, you must note that Iwarsson’s image corresponding to abdomen-in is very far from the concerted adjustments I asked you to project. The length between the lower back (lumbar) and lower ribcage is very far from being maximum, the upper torso is quite far back, the lower torso is arched backward, etc. But even with these poor adjustments of the different movements of the parts of the torso, the evidence is for all to see that pulling the abdomen in has visible consequence over the gesture as a whole.

A change in the habitual inhalatory movements strategy (including belly-in rather than belly-out) is a perfect procedure to train a pupil to feel wrong and develop her capacity to project conscious movements contrary to her sensory appreciation.

conscious guidance and control is grounded in the idea that you can detach yourself from the yoke of your sensory appreciation. Remember that the excerpt in which F.M. Alexander recommends to control directly the muscles of the abdominal wall to reduce a protruding abdomen and control the muscles [connective tissues] of the back comes just after a passage where he says that “sensation has usurped the throne so feebly defended by reason, and sense, once it has obtained power is the most pitiless of autocrats.“

I am not saying that you must trust me and take for granted what I have to say about the possibility and advantages of a strategy of abdomen-In strategy of concerted movements. The idea is to experiment for yourself with F.M. Alexander written indication and judge:

-

whether you can take a deep breath in contradiction with your habitual manner of use and the conditions of use which go with it, and

-

whether then you can decide from the evidence what is the best way to use your torso in the breathing movements.

A point that you can add to your reflection is this comment by Monica Thomasson who requested different professional singers to change their inspiratory technique. For her, professional singers can be classified in two opposite groups: the belly-out and belly-in (Bel Canto) inspiratory techniques. When both groups are asked to change their normal inhalatory behaviour (at the level of the abdominal wall action) they all report highly disturbing feelings.

“In fact, some singers found the belly-in condition highly uncomfortable, while others complained about the belly-out condition. (Thomasson, M.; Belly-in or belly-out, effects of inhalatory behavior and lung volume on voice function in male opera singers, 2003, p. 71)

Why do you want me to do that?

Apart from the different reasons which I have already explained before, you must understand that, for F.M. Alexander, the re-education of the breathing strategy is necessary when it interferes with the correct expansion of the mechanism of the torso.

When we start gestural re-education of the mechanism of the torso we have to contend with breathing habits which tend to interfere with the proper expansion of the thoracic part and the proper contraction/pressure of the abdominal region. In most of my student who have been trained with the modern Alexander technique the tendency is to make the breathing mechanism primary every time they are asked to think of taking a breath. As they associate the inhalatory breathing movement (inspiratory mechanism) with a subconscious release of the abdominal wall (abdomen-out action), they unknowingly

-

deprieve the abdominal muscles in the energy and tone necessary to the maintenance of efficiency in the digestive organs, and in the construction of the efficiency of the muscles of the back,

-

depress the diaphragm (a condition that F.M. Alexander associates with pushing out the pit of the stomach), creating an unduly low position of the diaphragm in breathing, and ,

-

expand the lower part of the ribcage (F.M. Alexander refers to “a faulty distension of the splanchnic area” (splanchnic means relative to the viscera and the abdomen) by allowing the lower spine to push forward.

The point is that, with a beginner, you have to contend with a mechanism of the torso which has not yet been consciously controlled. The flaccidity, lack or response and maleficient coordinations of the muscles and connective tissues are the result of the habits of subconscious guidance and control of the movements of the different parts of the torso. These conditions feel ‘right’ to your sensory appreciation and any progressive, constructive process away from them will feel wrong.

F.M. Alexander is talking about meeting these problems by using the indirect means through the agency of ordinary volition. What this means is that direct instructions like “I will raise the diaphragm” leave no room for the controlling mind to work upon, but if you ask yourself to draw in the pit of the stomach (indirect command to raise the diaphragm and widen the back at the same time) when you command yourself to lift the upper torso away from the lower torso and command a pull to the elbows to bring the upper torso forward, you can effect by your own means the necessary reeducation of the breathing mechanism. Your conception of the expressions “depress the diaphragm” or “raise the diaphragm”, that is the meaning you give to these words will be forever changed and you will read F.M. Alexander’s words in a new way, so that room is made for new conceptions and realisations.

At the outset of respiratory re-education one has to contend with a mechanism which has not been consciously controlled, and this can only be met by using indirect means through the agency of ordinary volition.

For instance, it is quite useless to ask anyone to raise or depress the diaphragm, but if he is asked to draw in or push out the pit of the stomach, first placing a hand on the part of the abdominal wall named, the mind has something to work upon; and this applies still more to other parts of the muscular system of the inspiratory mechanism.

(Alexander, F.M.; Introduction to a new method of respiratory vocal re-education, 1906, in Fisher, J.M.O.; Articles and lectures, p. 46)

I know very well that most modern Alexander technique teachers would choke on the idea of using such indirect means through the agency of ordinary volition. As you can see, I did not invent anything here and it is really F.M. Alexander who is proposing this procedure. This piece of information, i.e. that our colleagues and teachers

-

did not notice the importance and meaning of what F.M. Alexander was writing,

-

and never tested his model and written indications with controlled procedures,

does not change the fact that we must proceed to test whether it is possible and advantageous to give consent to performing these movements altogether.

Experimenting anew is giving a new impulse to certain intellectual functions which have been thrown out of play: the controlling mind can be re-instated to direct simultaneous movements which go contrary to our sensory appreciation.

This is not just a case of a change of strategy between abdomen-In and abdomen-Out. It is our whole attitude regarding new movements which feel wrong or “unnatural” which must be reassessed.

To finish my answer, I would like you to watch a very short recording of a singer (soprano Raquel Camarinha) who apparently has been trained in the Bel Canto style and knows very well how to draw the abdomen in when taking a short breath:

Fantastic article. I am not an expert at all, but a layman (and fibromyalgia patient) interested in movement and posture. In my own experience: when on the inhalation I squeeze the front-sphincter muscle of the pelvic diafragma the protruding of the belly becomes quiet impossible and there is an even greater internal feeling of increased stabilization and tightening. An inner stretching accompanied with outer widening and lengthening of my ‘position of mechanical advantage’. There’s another logical detail that should prove the the importance and rightness of your article: the ‘crura’ of the diafragma are connected to the lumbar spine. On the inhalation they contract and pull the diafragma down creating the necessary vacuum in the thorax which makes the air rush in. Releasing the belly out and curving the lumbar spine would undermine the functionality of this action. This pulling of the crura is most functional when the lumbar spine provides a strong and straight, that is not curved back or forward, support. In my own experience bringing it all together: monkey position rules (of mechanical advantage) combined with a front-sphincter active awareness (and smiling) on inhalation feels so right. Tnx for sharing