Introduction: It is easier to teach if you understand the words you are using

Part 1 of the chapter “Notes and Instances” in Man’s supreme inheritance, F.M. Alexander’s first book, is dedicated to the chapter titled: “What is the correct standing position, and the position of mechanical advantage ?”

He opens the chapter with a strong and extra short statement indicating various necessary conditions required to obtain a position of mechanical advantage in standing. He is not talking about “leaning forward in a position of mechanical advantage” (what is known by the moderns as the “monkey” position of mechanical advantage), but just about assuming a position of mechanical advantage in the standing gesture, that is with an upright mechanism of the torso. There is another position with an upright mechanism of the torso: it is the sitting “position”.

I plan to define what is a position of mechanical advantage in the upright sitting position using F.M. Alexander written indications so that it is possible for anyone to apply a test and check (control) whether their habitual sitting position can be seen as a position of mechanical advantage. As I will explain, there is no subjective criterion that could make one feel that the position of mechanical advantage is obtained, no feeling intelligence of the body which could tell us that we are changing toward the right conditions. To assume a position of mechanical advantage, F.M. Alexander explains that we must rely on a reasoned procedure of conscious guidance and control.

Understanding F.M. Alexander’s reasoned conception of the position of mechanical advantage and the two criteria (words) associated with it is essential to this goal, so I will start with the theoretical analysis of the criteria which he uses to define it. When this is done, I will introduce a procedure of conscious guidance which I use to ask my students to control their sitting gesture. The principle is simple: if they can perform the procedure, then they know that they are not far from having assumed the “correct” position.

Many modern Alexander technique teachers rejects F.M. Alexander’s idea of “position of mechanical advantage”, seeing it as a static incongruity when they theorise that “all is movements” in the use of the self. They consider that the fact that F.M. Alexander discarded the term after 1932 constitutes a proof that the concept is irrelevant or erroneous. I intent to prove that this reactionary attitude is unfounded and that the position of mechanical advantage of the mechanism of the torso is nothing else than (and has been replaced by) the primary control1 of the use of the mechanism of the self as a whole for the simple reason that the way of employing the mechanism of the torso in activity is a matter of the manner of reaction consciously planned to promote a “normal working of the postural mechanism2.”

What is very important in the sentence I have chosen is that we have a definition of the position of mechanical advantage in regard to two criteria. In F.M. Alexander’s words, mechanical advantage is defined as the result of assuming a position of stable equilibrium and a position which ensures a perfect mobility.

a position of stable equilibrium and a position which ensures a perfect mobility, unless his feet are so placed as to furnish at once a stable pose and a ready pivot and fulcrum.

I will leave for a moment the placement of the feet in its relation to the two criteria proposed in the first part of the sentence: “assuming a position of stable equilibrium and a position which ensures a perfect mobility“. I think that the criteria themselves deserve an inquiry into the meaning that these words could have in F.M. Alexander’s system before I deal (in the next article) with the particular case of the placement of the feet, i.e. what F.M. Alexander points out as a means to obtain the position of mechanical advantage in standing.

Very often, the fact that F.M. Alexander is saying something, announcing or expanding on a particular principle (a higher level concept in his system of ideas) of his technique, does not imply that we can readily understand what he is proposing. Reading the words, repeating the words or droning about the words does not likely lead to a correct understanding of the reality he is sketching out and which corresponds to his capacity of reasoning and practicing a particular psycho-mechanical solution to a given problem (and certainly not to ours).

When his concepts and reasoned practice are totally counter-intuitive as it is the case here, we are at a loss to grasp what he is talking about and we end up repeating words that are empty of reasoned meaning, even when it is only to caricature and reject his concept (you have certainly heard that some modern Alexander technique teachers are refusing the concept of position of mechanical advantage because it is a kind of “shape fascism”).

The more I give long-distance lessons to students and teachers of the modern Alexander technique, the more I find it necessary to invent practical procedures presenting practical psycho-mechanical problems which can only be solved by the pupil when they change their pre-conceptions in the use of the anatomical structure as a whole. Such a procedure acts as a pedagogical solution inviting the pupil to form a new conception, at the same time that it offers a practical test of the pupil’s comprehension and capacity to translate this understanding in practice to solve psycho-mechanical problems. If the student or teacher cannot display a satisfactory practical reaction when confronted with a stimulation, then the conception cannot be said to be changed in his/her attitude toward life, that is toward day-to-day solutions of basic psycho-mechanical problems which are always present. This is why I intent to present a practical procedure of conscious guidance in this article. I call it the stomping procedure.

The notion encompassing simultaneously the ideas of ‘position of stable equilibrium‘ and ‘position of perfect mobility‘ clearly represents an example of this state of affair [a counter-intuitive solution to a psycho-mechanical problem] in which the pupil cannot change his/her conception save by solving time and again, by his/her own means, and improving his/her solution to a particular psycho-mechanical problem of coordination.

The purpose of the “stomping procedure” is

-

to provide such a psycho-mechanical problem of coordination and,

-

to review through our attempt at its solution the conception we have of the terms position of stable equilibrium and position of perfect mobility.

I am now going to show that to adopt a new reasoned conception, it is first necessary to realise what is the pre-conception, the conception based on our feeling experience that we should eradicate in order to create space for the new one.

In colloquial use, equilibrium and stability are obvious words logically based on what we feel

Equilibrium and stability are fundamental scientific concepts in Newtonian mechanics which differ markedly from the day-to-day, familiar use of these words. Even with students who have received a formal training in mechanics, the grasp of these concepts is often terribly superficial because they clash with the colloquial use of these same words. I let you imagine the state of affairs in the ranks of teachers of the modern Alexander technique who are recruited amongst dance, music and other somatic disciplines.

Support has been given to the theory that ‘knowing a concept by name’ does not imply in-depth understanding nor a versatile capacity to apply it in reasoning out solutions to new problems; researchers have established after testing graduate students in scientific universities that they had “erroneous conceptions about the concepts” of equilibrium and stability (see Canu, de Hosson and Duque, 2014). Despite being taught in all secondary school curriculums, “there is little clarification of the differences between the [scientific] concepts or the ways in which they are linked. We believe that this leads to much confusion and incomprehension among students. […] A poor grasp of the above fundamental concepts may result from previous learning experiences. More specifically, certain difficulties seem to be directly linked to a lack of understanding of these concepts, while others are related to misconceptions arising from everyday experiences and the inappropriate use of physical examples in primary schools” (Canu, M., de Hosson, C, Duque, M.; (2014) Students’ understanding of equilibrium and stability, the case of dynamic systems, Int. Journal of science and education, p. 1).

Most readers of F.M. Alexander’s books assume that he knew nothing of the academic [counter-intuitive] definition of the concepts of equilibrium, stability and mobility and, therefore, they tend to read his words at the least developed level of physics, that is, a naive, rudimentary and unsophisticated understanding of the meaning that can be attributed to these words. When they read that the pupil cannot assume a position of stable equilibrium and a position which ensures perfect mobility unless he can place his feet in certain conditions, they do not understand “in-depth and in logic” what he means by his two criteria definition, they just presume that they have had a direct experience similar to the one he could construct for himself because they have been manipulated time and again by a touch-teacher who was supposed to give them “the correct experience” and despite the fact that F.M. Alexander never accepted to be manipulated in any way by a touch-teacher. In other words, their conception of the criteria is subconscious, colloquial and unquestionable because it is grounded in their somatic perception.

In the sphere of conscious guidance and control, the situation is even worse than in science teaching, because in the somatic teacher training centers, nobody really cares about explaining or questioning how concepts, principles and orders relate to and structure the practice of the technique. I have started to go against the flow and to talk to the students and teachers who are eager to start this kind of questioning.

I have never heard a modern Alexander technique teacher comment on the curious use of words in this sentence [‘stable equilibrium’, ‘position which ensures perfect mobility’], nor about the necessity to check whether F.M. Alexander could have (or not) misused the scientifically established meaning for this combination of words [stable equilibrium]. I think that, when reading this passage, the first Alexander technique teachers and most modern Alexander technique teachers after them just assumed that the founder did not realise the meaning defined by the scientific use of these words, and they deemed not necessary to investigate whether the meaning they were themselves giving to these words could be a misconception of their true significance in physics.

This amounts to say that the sentence we are considering was simply discarded

(A) because it meant any of the things you wanted it to mean in colloquial English—therefore it meant nothing— and

(B) because the first generation teachers really believed that F.M. Alexander’s books could not describe nor plan the experiences they were having under his hands through his written words.

Despite the fact that F.M. Alexander had followed the opposite course (he reasoned out how to change his own equilibrium), they really believed in the primacy of somatic experience over reasoning.

The trivial definitions of equilibrium and stability

The words equilibrium and stability have a meaning in spontaneous reasoning based on [i.e. abstracted from] common experience, that is based on the sensory appreciation of the subject. In the subconscious pre-conception (conception based on what people feel),

-

‘equilibrium’ is the capacity to resist falling in conditions in which most people would think/feel they could/should fall and,

-

‘stability’ is the result of being capable to resist postural disturbances (mostly by stiffening certain joints and parts and using as many props as available to stop the structure from falling). Common stability is not conceived as a qualifying criteria of a state of equilibrium; it is viewed as a state of the body just like equilibrium.

As a result, the two concepts are mixed up on the subconscious level and the subject cannot properly separate and establish a working hierarchy/relationship between the two. When asked to solve a psycho-mechanical problem regarding the changing state of their own anatomical structure, most students will spontaneously think that equilibrium is a particular characteristic of stability because this is their conception of these words, AND they will react accordingly, trying to use the arms and lower limbs as props for the stability of the mechanism of the torso, without realising that in their conception of stability, they thoroughly sacrifice the second criteria —the mobility of the parts of the structure.

The central question is that in the trivial use of the words, they only describe a result, a spontaneous coordination and an unreasoned postural reaction. Most readers do not take these words as indicating certain criteria which can be understood and employed to plan and control a series of acts to obtain a new state of coordination.

This prevalence of the secular use of the words also explains why most people do not see the incongruity of using the two words side by side, because for them equilibrium is a feeling and stability is also a feeling with very little to tell them apart, so they can as well be joined together to form an even nicer couple. From a marketing point of view, the great thing is that the connotation, the subjective and cultural meaning for the series of words {stable, equilibrium, perfect, mobility} is good so that their addition will sound even better when trying to convince people.

If F.M. Alexander is just trying to seduce people, he is doing a great job. If on the opposite, he is trying to lead them out of ignorance and narrowness, the least we can say is that he is not going through for in classical mechanics, that is in a reasoned approach, the state of affairs cannot be more different because these words have a precise meaning which can be used to anticipate and think out solutions to new problems.

In mechanics, equilibrium is not a feeling, it is special state which must be calculated, reasoned out by analysing all the forces and momenta acting on a system (either mathematically or with the graphical method), many of which cannot be felt.

By definition, equilibrium is a stationary state for variables describing an isolated system (when describing a non-isolated system, one may speak of dynamic equilibrium). In other word, to establish that a system is in a stationary state, the net force acting on the system must be calculated to be zero (all the forces and moments applied to the system must oppose each other so that their sum is null). It is obvious that the many forces acting on a system cannot be felt at once, as a whole, by a sentient being and analysed so as to form a correct representation of the state of the system. Equilibrium belongs therefore to the sphere of reasoned concepts.

This means that a system calculated to be in a stable equilibrium is most often not “stable” in the common acception of the term (understood as ‘that which does not move’), in the sense that, “when it is already in an equilibrium state” (net force equal zero), the least force will set the system in motion. In common subjective experience, the ‘equilibrium state’ of an upright structure means a feeling of total insecurity and the possibility of falling equally easily in any direction. This is particularly true of a “position of mechanical advantage” in standing, involving unfamiliar psycho-physical experiences which feel wrong, discomfort frequently amounting to irritation and a sense of unsteadiness in equilibrium. It is important to remind the pupil that a reasoned [calculated] state of equilibrium will trigger “a sense of unsteadiness in equilibrium” the closer the pupil is getting to a state of equilibrium. F.M. Alexander never wavered on this consequence of conscious guidance:

a number of things, all going on, and converging to a common consequence

The adjective stable qualifies a particular state of equilibrium

The adjective ‘stable’ when used in mechanics to qualify a state of equilibrium has a totally different meaning from the familiar use of the word. Stability in mechanics is even further removed from feelings than equilibrium as it is a peculiar characteristic of an equilibrium state which informs about the future of the equilibrium, that is, it predicts the outcome for the current state of equilibrium after the system in equilibrium has been subjected to a perturbation.

A system is said to be in a ‘stable equilibrium’ state when it tends to return, within a finite period of time, to the original equilibrium state after being subjected to a perturbation. When displaced from equilibrium, a system in ‘stable equilibrium’ experiences a net force or torque in a direction opposite to the direction of the displacement. More precisely, when we say that the system is in a state of ‘stable equilibrium’, we predict that the system will return to its state of equilibrium on its own after momentarily being displaced from its state, without any additional external action and within a finite period of time.

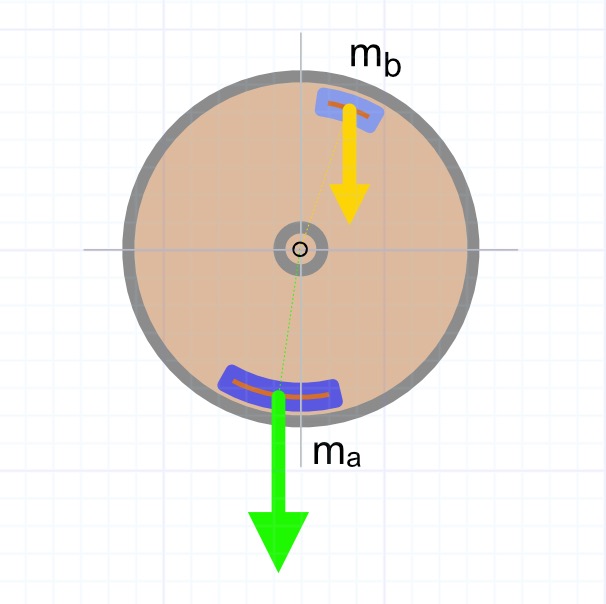

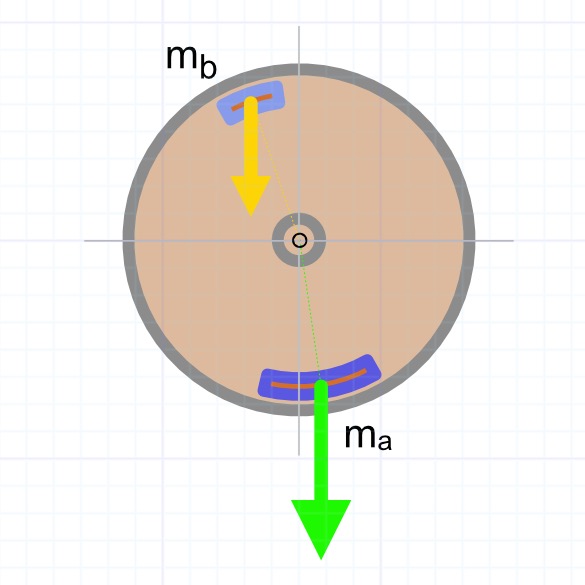

Imagine a mechanical system composed of a wheel turning around an axis. The wheel is an homogeneous structure which center of gravity is located on its geometrical center where the axis of rotation is located —as a result, it is in a state of neutral equilibrium because any perturbation will make the wheel turn and it will stop after a finite amount of time in a random angle relatively to the original position. A position of stable equilibrium cannot be found for a perfect wheel.

To give an example of a system in a state of stable equilibrium, the system I am considering is that of a wheel to which two ‘flyweights’ {ma, mb} are fixed on the wheel at different locations of its circumference. Adding flyweights of different mass set in this way transforms the wheel in a non-homogeneous mass structure and completely changes the calculation of the state of equilibrium of the system.

The wheel is displayed as a system in equilibrium in the peculiar geometry chosen on the diagram because all the forces and moments applied to it are opposing each other. Unless it is moved by an external force, this system will stay in this particular geometry. This is a consequence of the difference in mass of the two flyweights and of the difference in position on the circumference of the wheel.

This system can also be said to be in a state of “stable equilibrium” because if a perturbation affecting the axis or the wheel is applied, the system will enter in rotation but, after a finite amount of time, it will settle back into one of its two “positions” of stable equilibrium (the geometry of the system is such that there are two positions of stable equilibrium in this case). We can predict that the wheel will stop its motion after a perturbation at one of its two definite positions of stable equilibrium.

We see therefore that ‘Stability’ as a mechanical [scientific] characteristic of a ‘system in equilibrium’ has nothing to do with the subconscious meaning of “being stable”, that is of “blocking movements in as many directions as is possible”. The concept of stability helps to predict the future of the system after a kinematic perturbation.

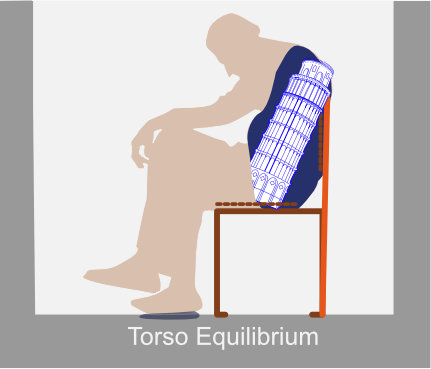

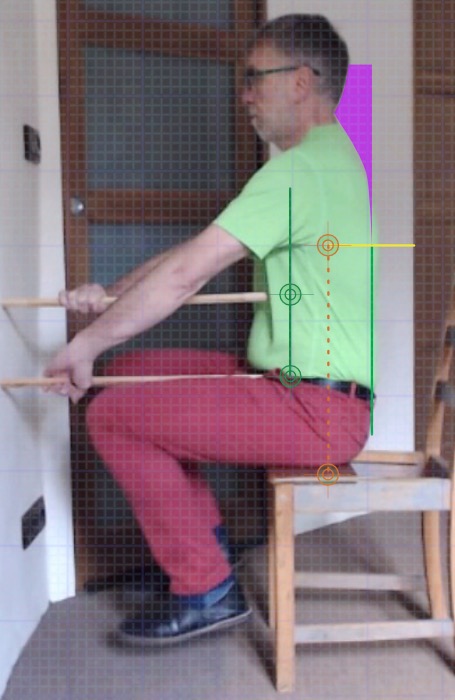

The two concepts are therefore closely related in the two different frameworks, but in a totally different way. In the subconscious experience, the two concepts are pre-intellectual concepts and their relationship is not determined or easily identifiable as it is a proximity between two feelings. Most subjects in sitting are seen to be fairly stable (they resist falling) in the mundane sense of the adjective but they place themselves in a geometry which is absolutely not a state of equilibrium which ensures [perfect] mobility. Upon cursory inspection, the gesture described in the following diagram does not satisfy the two conditions of a position of mechanical advantage as defined by F.M. Alexander. The mechanism of the torso is not in a position of equilibrium (without the back of the chair prop) and the mobility of the torso relatively to the limbs is severely restricted.

Now that these clarifications are given, we have to deal with the questions raised by the sentence written by F.M. Alexander regarding the prerequisite conditions of a “position of mechanical advantage” : it is possible to consider that the complex system of the human anatomical structure could be placed in a state of “stable equilibrium” which according to the framework of mechanics could come back to its original state after a postural perturbation? It is obvious that the habitual responses to perturbations —as seen when a pupil is subjected to an imbalance (real or felt)— do not comply with the scientific definition of the expression. Could these habitual reactions be changed and a new position assumed that would display the mechanical criteria stated by F.M. Alexander?

Furthermore, as F.M. Alexander is talking about “assuming a position of stable equilibrium”, could it be that there is such a position that could be consciously guided and performed against the habitual response? This would imply that certain “starting geometrical positions” and the movements by which these are assumed should introduce not only perfect mobility but also “spring effects” (or “antagonistic pulls” as F.M. Alexander named them) which are absent in “positions of mechanical disadvantage” but which could be incorporated in the calculation employed to verify the state of equilibrium of the particular position. In theory, we are postulating that these antagonistic actions could well bring back the structure into a stable equilibrium after each postural perturbation without any effort from the subject.

This remains to be demonstrated in practice and this is what I am going to present in the last chapter of this article.

How a position that ensures a perfect mobility could be considered as stable?

Before starting with the practical procedure, there is still one indication given by F.M. Alexander that I want to resituate. The second part of the first sentence put forward by F.M. Alexander —that is ‘assuming a position of mechanical advantage which ensures perfect mobility’— goes against the idea that there could be or should be anything ‘stable’ [in the common or subconscious use of the word] in the concept of ‘position of mechanical advantage’ formulated by F.M. Alexander. This part of the sentence introduces a serious difficulty to view F.M. Alexander’s statement [only] as a subconscious cliché eradicating the difference between stability and equilibrium.

This brings me back to the question of the distinction between

-

having a student experience something and,

-

making a student experiment a given theory in an experimental setting.

Most somatic teachers believe that the observation of a real phenomenon by direct experience will help students conceive correctly of a principle, and that the repetition of a physical experience of being led by a masterful touch-manipulator into what is supposed to be a position of advantage (because it feels light and free) will be sufficient to inscribe in the pupil’s mind the concepts and the means (coordinated movements) subordinated to these concept which are necessary to obtain such a result by themselves.

This is were there is a major failure to understand things properly when they are related to the construction of a conception (construction of a scientific concept) which goes against somatic intuition. It is instructive to expand our horizon to other spheres of teaching which show that counter-intuitive concepts are not mastered by students because they have repeated observations in certain conditions. This is exactly what is reported by Duque & al. regarding the understanding of equilibrium and stability.

“However, many studies also show that the observation of a real phenomenon (whether natural or through experience), far from enlightening students, often lets them see only what their preconceptions lead them to observe (Champagne & Bunce, 1985; Gunstone & White, 1981). For example, in case of moving objects, as pointed out by Kariotoglou, Spyrtou & Tselfes (2009, p.857), a direct experience could drive students to automatically make a difference between motion and rest instead of considering one (rest) as a special case of the other (motion). Moreover, the presence of ambiguous sensory information, such as the velocity or the acceleration of the trolley or pendulum, is an aggravating circumstance of this effect that can strongly skew the gathering of information about the system by influencing the orientation of students’ erroneous conceptions (Brewer & Lambert, 1993). (Canu, M., de Hosson, C, Duque, M.; (2016) Students’ understanding of equilibrium and stability, the case of dynamic systems, Int. Journal of science and education, p. 10)

The example chosen by Duque as illustration, i.e. a direct experience could drive students to automatically make a difference between motion and rest is relevant to our discussion. How is the reader going to understand the concept of a position of mechanical advantage, a position which ensures perfect mobility, if he/she has constructed a subconscious pre-conception of a difference between motion and rest? How could he conceive instead considering one (rest) as a special case of the other (motion)?

The somatic pre-conception is that a position is static and stable by definition. A position (of mechanical advantage or disadvantage) is viewed as an absence of motion and not as a combination of different movements (means-whereby) applied at the same time and which give the impression of a stable pose. If such is the framework F.M. Alexander was working into, how could we think that a certain position could ensure a perfect mobility?

The answer to that last question is given during the practice of the “stomping experiment”.

I always start to launch the experimental conditions for bringing the new conception to light with a procedure which involves the sitting gesture instead of the standing gesture. The reason why the procedure involves the sitting gesture is because it is much easier for a beginner to perform the new equilibrium requirements in sitting than in standing.

There is another procedure that I use to test the two preconditions of stable equilibrium and mobility which make the position of mechanical advantage in standing, but I only ask advanced students to attempt it because of the overwhelming sense of unsteadiness in equilibrium that floods the sensory appreciation of the subject at its onset and, more often than not, leads to total failure unless the student has developed a solid detachment from the feeling sense and a swift capacity to concert unfelt movements. For record, this standing procedure I call the “charioteer procedure” and F.M. Alexander is seen performing it, lifting one leg and passing it over the back of chair placed in front of him. You can have a look at it at the end of F.M. Alexander’s 1951 film made by the Watts family.

This is not to say that the stomping procedure is comfortable and that it does not require a dose of detachment from the dicktats of the feeling sense.

To present the psycho-mechanical problem raised by F.M. Alexander to my students, knowing their subconscious pre-conception regarding the concepts of equilibrium and stability, I prefer to direct their attention to the position of mechanical advantage of the mechanism of the torso, deliberately setting aside the question of the placing of the feet and legs.

Most of my students start their lessons with the belief that placing the feet and the legs is the main solution of the problem of equilibrium they face in the sitting gesture —in other words they have the habit of mind of relying on the legs, feet, arms, elbows and any other prop external to the torso to maintain what they consider is the resting stability (the fixation) of the torso on the chair.

I therefore introduce the notion of equilibrium of the mechanism of the torso as a geometrical problem to be solved: I explain that the torso is said to be poised, that is ready to move as easily in a forward or backward direction, when the frontal parts of the sitting torso are aligned on the same plane —and no prop (external or from a limb) is used to maintain the torso in the upright position. For the pupil, this is pure speculation, but I tell them that I will soon give them a dynamic test of their reaction to show that there is some truth in this strange re-adjustment of the parts of the mechanism of the torso.

Sometimes, the students themselves realise that there is a problem in their sitting gesture and in their conception of rest as opposed to motion: the end-gaining solution of stabilising the torso with the legs (or upper limbs) brings severe penalties which can disrupt the lives and activities of the pupils.

One of my student is playing the organ, an instrument in which not only the upper limbs must remain nimble (therefore they must resist the habit of using the keyboard as a prop) but also the feet must fly from one pedal to many others so that both her feet and upper limbs are more often in the air and cannot “stabilise her torso”. We found that her habitual reaction to having both feet in the air totally compromised both her torso equilibrium and its expansion, leading to unwanted activity and fascial pain syndromes in the hands, shoulders and back. The only solution was for her to change her conception of the notion of position of mechanical advantage in sitting in order to establish a reasoned reaction to the stimulation associated with the task of playing the instrument. I explained the stomping procedure to her so that she could have a criterion to evaluate in which direction she had to work to effect a constructive change.

This is to say that a pupil can discover the counter-intuitive concept of ‘position of mechanical advantage’ according to F.M. Alexander’s dual definition of the problem. All that is asked of him/her is to explore on his/her own (without any touch/external guidance) the solutions to a procedure of conscious guidance of a position of mechanical advantage in sitting.

As to the case of my student, if after learning the discipline of conscious guidance of the mechanism of the torso, she is seen to be able to concert the two criteria of stable equilibrium and perfect mobility for the mechanism of the torso despite the stimulation of her art form, then she could clearly judge that she is going in the right direction of change to alter the faulty conditions evoked by her reaction to the particular task she faces when playing the organ.

The procedure of conscious guidance starts with the establishment of geometrical boundaries for the movements of different bony parts of the torso. The lower and middle (and later upper parts) of the torso are moved to align their frontal spots on a vertical plane anchored on the base of the torso, that is, the vertical plane is conceived as passing through definite bony spots at the front of the lower part of the torso.

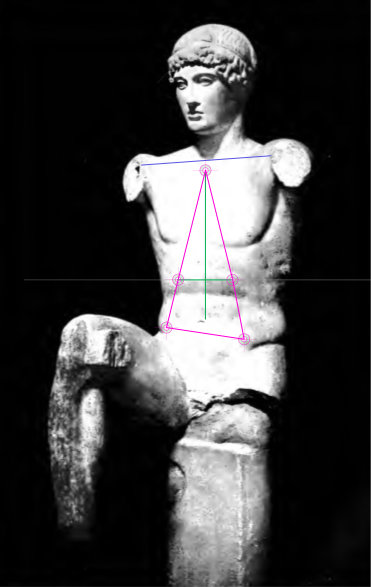

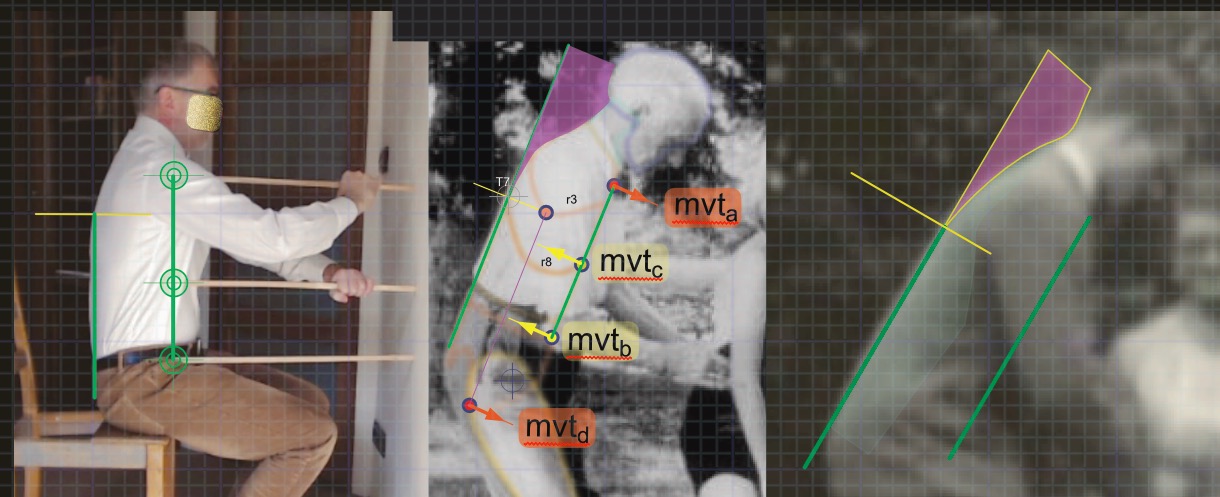

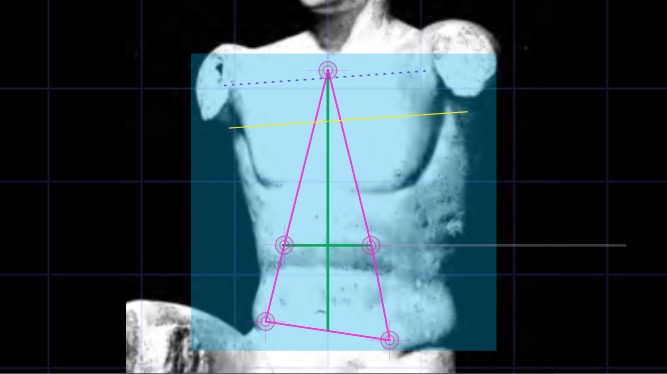

At first, it is necessary for the pupil who is not used to direct several movements towards a visuospatial plane target, to use rulers in order to make the visuospatial plane [alignment] and the movements of adjustments to reach it more concrete in his mind. As I have shown elsewhere, it is simple to establish a series of directions for the movements of the different parts of the torso in order to project a geometrical adjustment of the mechanism of the torso which corresponds in all points with the lengthening and widening of the torso F.M. Alexander is seen projecting in his photos and films. On the photographs below, you can see the expression of the orders “back back” (lower and middle torso backward) and “upper torso comes forward” projected simultaneously to establish a lenghtening frontal plane of the torso. F.M. Alexander is seen consistently to direct the movements of the different parts of his torso in this adjustment as a whole.

I have placed three anatomical landmarks on the frontal plane of the torso of F.M. Alexander not because I can see them on the photograph, but because I know that the only way to present a flat lower back and a great forward hump (purple distance between the line of the back and the back of the upper torso) is to align the spots on the frontal plane and expand the triangle thus constituted.

I describe this readjustment according to a reasoned geometrical model either “the harmonic expansion of the torso” (Delsarte’s expression) or more simply as “lengthening and widening the back” (F.M. Alexander’s expression).

In this pedagogical ‘static phase’ using rulers as props, the different parts are moved at the same distance from a surface of reference, one after the other, starting with the lower torso first to establish the base of the vertical plane for the frontal parts of the torso. The pupil will quickly realise that in his normal use of the parts of the mechanism of the torso, the movements of the different parts are interdependent. This means that after measuring the distance from the lower part of the torso by means of a movement which makes the bone connect with the wall through the ruler, he must continue3 this movement with the lower part when measuring the distance from the middle torso to the wall for otherwise, moving the middle torso in isolation will disrupt the position of the lower part of the torso.

Seen from the side, these concerted movements produce a position of the torso commensurable to —that can be measured using the same criteria as— that assumed by F.M. Alexander and his first teachers in all their photographs.

It is shown to the pupil that these concerted movements when performed to create the maximum vertical distance between the spots are the means-whereby movements necessary to expand the torso, that is, to obtain the END expressed habitually as “let the back lengthen and widen” and which can be observed in the gestures of F.M. Alexander and his first teachers. The new position of the head relatively to the torso and the freedom of the neck are consequences of this new geometrical (reasoned) organisation of the movements of the different parts of the torso (the novice pupil is never asked to think of the neck or head, or to do any movements with them— he has so many things to think at once in a short time that there is no way that he could entertain ideas about the head and neck when performing the steps of the procedure).

I call this position the “position of mechanical advantage of the torso in the upright position”.

Once this is achieved, a postural perturbation is introduced by asking the pupil to stomp his feet strongly against the floor while directing (ordering) the same concerted movements of all the parts of the torso. Of course, he must find a way lift BOTH his legs very fast in the air and to stomp his feet, without losing the geometry of the mechanism of the torso which his concerted movements have achieved. The stomping procedure requires the torso to stay in the same geometry and the same series of movements must be directed for this constant readjustment to take place.

All my students consider deep down in their embodied cognition that the feet, legs and arms are the movers and stabilisers of the torso and no amount of reasoned discussion can help them to change that subconscious pre-conception. There is no way to make them reason out from their embodied cognition (their somatic experiences) that the specific control of the feet and leg should primarily be the result of the conscious guidance and control of the movements of the different parts of the mechanism of the torso, because this idea runs contrary to their pre-conception and embodied intuition. Without the help of a practical procedure, they just cannot reason from the basis that the torso could be the main mover and stabiliser of the coordination of the structure and limbs because their psycho-physical experience based on what they have always felt and believed is contrary to that concept.

F.M. Alexander can write everything he wants about his “new concept”, but the students cannot read his words for what they say because they cannot graps the meaning of the concept either intellectually or practically.

This does not mean that it is impossible to bring a pupil to face his preconceptions and open his mind to a new level of reasoning. The stomping procedure is the perfect problem to discover the consequences of the conscious guidance and control of the mechanism of the torso.

In finding the solution to the stomping, the pupil will discover that, if the mechanism of the torso has been organised by a series of movements so that

-

the frontal parts are on the same vertical frontal plane AND

-

the linear distances between the spots on the frontal parts are maximum, that is there is also a vertical expansion between the lower and upper cavities of the torso,

then there should be no visible (or felt) preparation in the legs and torso prior to the lifting of the legs in space. The internal muscles and biomechanical spring tissues (fascias) of the torso are so stretched by the antagonistic movements of the parts that they produce a potential catapult effect which will become visible when the operator will give simultaneous consent

-

to lifting the legs and

-

to concert the movements of the parts of the torso altogether toward the imaginary plane defined in the first phase.

Lifting the legs for stomping should be the result of the same concerted movements that were used to assume the position of mechanical advantage and NOT of any direct action of contraction of certain groups of muscles. The pupil is to realise that the position of mechanical advantage is the position which ensures the antagonistic pulls which are responsible for the building of the catapult effect of the legs and the elastic “stabilisation” of the torso as a whole. When the ‘catapult effect’ (antagonistic pulls) is released, giving consent to the concerted movements of the different parts of the torso towards an imaginary vertical plane (seen as the green “line of unity” from the side) will not bring the parts into the reasoned geometrical adjustment because it is already there, but they will allow the pupil

-

to inhibit any movement of the torso as a whole to lift the legs, and

-

maintain the integrity of the structural expansion of the torso which brings about an elastic relationship between the torso and the legs both when the legs are lifted and when they strike back on the floor with an heavy stomping sound.

Obviously these movements of the parts of the torso are not seen on the video, but you must understand that, without projecting them, the operator could not lift the legs nor stomp them on the ground without the stable equilibrium of the torso to be lost.

Most people viewing an illustration of this procedure will tend to see only what their preconceptions lead them to observe, that is, a position fixed in space. Seeing a torso propped against a wall with several rigid rulers will only serve to reinforce their preconception about a sharp divide between posture and coordinated motions.

They will fail to realise that any sitting position is the result, that is the END, of a series of means (means-whereby of this particular readjustment of the torso as a whole) which are the series of movements planned and performed with the different parts of the mechanism of the torso by the individual engaged in the procedure of conscious guidance. But they also need to discover another factor: because these movements create passive antagonistic pulls, they are “continued” in the apparent fixity of the position of mechanical advantage in sitting and poised, ready to be released as long as the pupil inhibits his old habitual way of “fixing the torso and legs”.

Now, if you look closely at the sitting position described in the above illustration, you will realise that the legs and feet are lifted in the air. At the moment the picture is extracted from the film of the procedure, the feet and legs are not steadying the mechanism of the torso in space. It is the opposite that is taking place, and we could say that the movements of the legs are a major postural perturbation which the torso must compensate.

Let’s repeat the last commentary and bring it in perspective with F.M. Alexander’s sentence: at the moment the photo is taken, the legs cannot be held responsible for the ‘apparent stability’ of the torso in space: the specific control of the legs and feet is the result of the conscious guidance of the movements of the different parts of the torso and the stability is clearly relative to the state of equilibrium and not a reduction of its mobility. It does not matter that the movements of the different parts of the torso are frozen in time by the still picture, because the vertical arrangement of the torso must be explained by something other than fixity on the chair. This procedure explains what we mean when we say that the torso is seen as the tree and the arms and legs are seen as its branches. The torso is clearly the mover of the legs in the conditions of mechanical advantage. The expansion of the torso is the reason both for its equilibrium and for powering the movements of the legs up in space.

You will have to figure out that, in order for the bony parts of the top and middle torso to stay in contact with the rulers and for the rulers to stay against the wall, there must be a series of movements of the different parts mentioned to oppose the movements (momentum) of both legs which are thrown in the air.

Phase 2: The dynamic phase

Once the operator has developed the necessary mind control over the movements required to organise both

-

the position of mechanical advantage of the mechanism of the torso and

-

the catapult lifting of the legs,

it is customary that the difficult phase will be to stomp the feet down without having the upper torso fall forward in the same direction (forward and down). This phase will appear magnified as soon as the operator is asked to project the concerted movements of the different parts of the torso to stomp the feet without the concrete help of the rulers to resist the forward direction when fast moving the legs down.

Once this first experiment/test of conscious guidance against the postural perturbation of lifting and stomping the feet is obtained successfully by the pupil —when he/she can consciously direct the movements of the different parts of the torso as a whole in MOTION and at REST— so that the torso is in equilibrium on the chair, the next step is to ask the pupil to set the rulers aside and to command the movements of the different parts of the torso without any prop, but following the same reasoned geometry. The perturbation is used to test the reaction to the effect of the strong momentum of the legs upon the torso, in other words, to evaluate whether the torso system is in a state of stable equilibrium.

When the rulers are removed, the operator is asked to project ALTOGETHER the movements of the different parts of the torso toward an “imaginary vertical plane” parallel to the wall in front of him and passing through the frontal parts of the lower part of the torso, irrespective of the movements of the legs. The pupil cannot feel all these adjustments projected altogether, but he can project his expression of the orders of movement to a still camera to control the outcome of his conscious guidance. From viewing his performance objectively, he can reason out how to change his novice way of projecting the orders —detaching himself more and more from the feeling sense— so as to develop a solid guidance by a process of reasoned change. What I call discipline is training oneself to act according to objective orders, rules and principles. The ‘principles’ are stable equilibrium and perfect mobility, the ‘rules’ are the geometrical control of the expansion of the mechanism of the torso, and the ‘orders’ or “new orders” are the orders of movements which lead to the expression of the geometry (position) of mechanical advantage of the noble pose on a video recording.

Take the case of the reaction of the pupil prior to stomping, that is how the torso is seen to move as a whole when the legs are moving fast down to stomp the floor.

When the legs are moving down, the habitual reaction filmed by the camera is to incline the upper torso forward, in the same direction as the legs. The scene will give the impression that the elastic tissues of the back, instead of maintaining the torso linked to the back of the legs, stop all resistance and all connection, and the torso is falling forward and down due to the acceleration of the heavy thighs. The problem is that the upper torso is seen to fall forward, yet, to change this manner of reaction, the uppper torso movement should still continue to be directed forward in opposition to the movements of the middle and lower torso. This direction goes contrary to the spontaneous idea of stopping the upper torso to move forward when the legs are accelerating their movement downwards, but the movements of adjustment of the middle and lower torso that have been reasoned out from the start to be directed in a backward direction must be performed with a stronger intention in opposition to the movement of the upper torso despite the feeling of falling forward communicated by the movement of the legs and the habitual non disassociation of the movements of the lower torso and the lower limb. The means-whereby principle in activity is to continue working with all the orders at the same time, harmonising the series of orders of movement instead of focusing on one individual [direct] solution to the “problem”. The direct solution is always based on the subconscious, embodied experience, that is the faulty conception that the pupil is targeting for a change.

Working in this way and controlling on film that the concerted orders have the desired effect will make the pupil realise that he can direct the movement of the upper torso, NOT relatively to the movement of the legs (this would be a “direct” reaction) but still relatively to the movements of the two lower parts of the torso mechanism (indirect guidance).

It is then observed how the lifting and the stomping of the feet progressively fails to affect the stable state of the torso as a whole (prevention), and the accuracy of the guidance of all the movements of the parts. With this procedure, and with the objective control it provides on film, the pupil will know by himself whether he/she is working in the right direction, that is toward the expression of the criteria of stable equilibrium and mobility.

-

that the torso is not supported by the legs or arms,

-

that the movements of the legs and feet are introducing a strong postural perturbation on the system.

The equilibrium of the mechanism of the torso as a whole is seen to be stable against the postural perturbations generated by the fast movements of the lower limbs, either when they are lifted in the air or when they are hitting back on the ground. As the conditions of equilibrium and mobility are secured, we can therefore say that this position of the mechanism of the torso is approaching (going in the right direction toward) the expression of the concept defined as position of mechanical advantage in sitting by F.M. Alexander, because the two criteria of “stable equilibrium” and “perfect mobility” are fulfilled.

The directions of the different movements of the parts of the torso are creating conditions of elasticity and disponibility for the whole structure which are apparent when the legs are lifted and stomped, but the student is woken up to the fact that the rest position (sitting still) must be considered as a special case of the motion position, that is the concerted motions of the parts necessary to assume the “position” are maintaining conditions of geometry and elasticity even when we cannot see these antagonistic actions. It is not because the movements are not visible in rest that their reality can be discounted, therefore the new “rest gesture” is composed of movements.

If you observe closely the onset of the movement of the legs off the floor on the video presented in this paper, you will see no preparation whatsoever visible in the mechanism of the torso or in the legs prior to the very moment when the legs are lifted in the air: this means that the antagonistic actions (spring catapult conditions) are already present in the rest position. All that is necessary to lift the legs is to allow for the act to take place and the conditions of stretch of the elastic tissues of the torso will simply

-

power the fast movement of the two legs,

-

provide the elastic resistance necessary to oppose the momenta generated by the fast moving “heavy” legs, and

-

maintain within reasonable margins the conditions of expansion of the torso so that the torso stays in equilibrium on the chair seat.

In conclusion

My point is that to bring about the normal working of the postural mechanisms as a whole (that is the effectiveness of the equilibrium reaction) the primary control is the control of the simultaneous movements of all the parts of the mechanism of the torso. Therefore, the primary control of the use of the mechanisms of the self is the capacity of mind to direct and control the different movements of the parts of the mechanism of the torso in activity to assume a position of mechanical advantage, i.e. a position which satisfy the criteria of stable equilibrium and perfect mobility.

“My experience as a teacher of the technique is derived from demonstrating daily to every one of my pupils that there is a primary control of the use of the mechanisms of the self, and that in taking full advantage of the influence for good in correctly employing this primary control we hold the key to the bringing about of the “normal working of the postural mechanisms” as a whole. (Alexander, F.M.; The universal constant in living, Chaterson L.t.d., 1942, third edition 1947, p. 115

My surprise was massive when I discovered that the stomping procedure, once mastered, could be demonstrated with equal simplicity with the head completely pulled back or forward and down. This meant that the position of the head was not in any way essential or “primary” to the attainment of the normal working of the postural mechanisms. With the practice of the new found “stomping procedure”, the new position forward and up of the head relatively to the torso had just become a consequence of the correct organisation of the different movements of the parts of the mechanism of the torso.

It is true that many of my pupils (I was such a one) cannot move the parts of the torso in a proper coordinated way (with properly coordinated movements) without involving a movement of the head. This just indicates that an incorrect movement unconsciously performed has asserted itself and has become primary and hinder the performance of the correct and co-ordinated movements as ordered. This movement of the head is not “primary” in the sense that it allows the movements of the parts of the torso to obtain a position of mechanical advantage. The proof is in the pudding: the pupil will discover that he can order himself to inhibit this movement of the head or when that is too difficult, that he can still perform the correct and co-ordinated movements of the parts of the torso with a new movement of the head that is, a movement in the opposite direction as that of the subconscious “primary” movement of the head. Curiously when this newfound independance of the coordination of the movements of the parts of the torso from the old “primary” movement of the head is achieved, it takes a minute for the pupil to suddenly become capable to inhibit perfectly ALL movement of the head when the different movements of the parts of the torso are consciously directed to assume a true position of mechanical advantage.

As a young modern Alexander technique teacher I had for years told my students that the primary control of the use of the self was a certain relation between the head and neck with the rest of the organism. All the community of the modern Alexander technique believed and professed the same thing —and the fondation of that belief was just because they had all felt a great somatic experience when manipulated by touch-teachers who repeated that strange litany! Many years later, I still bump into old pupils of mine who are happy to tell me that they still think of directing the head forward and up in their daily life and I cannot but feel a sort of shame (and anger) when I look at their [more than ever] harmful postural coordination in sitting, standing and walking. It is just so obvious to me now that just-thinking of releasing the neck and directing the head forward and up is not the key to bringing about the normal working of the mechanisms as a whole that I see clearly that I led them into a path of ignorance and narrowness where no miracle ever happens.

“I hold that we have reached a stage in our development when all attempts to remove the cause or causes of suffering which do not come within the scope of reasoned, practical procedure must, with the broader view, be definitely abandoned, and that we should ere now have passed that stage of ignorance and narrowness which permits the human creature to entertain for a moment the idea of a miracle. (Alexander, F.M.; Constructive Conscious Control of the Individual (Eighth edition, 1946), p. 61)

Footnotes

- “The physiologist may know the names of the muscles and the particular function of every one of them, but in the matter of employing them to the best advantage in a unified working of the human organism in daily life, this knowledge does not help us very much. The reason is that the way of employing oneself in activity is a matter of the manner of reaction, and the influence of this on the subject being observed is not taken into account by the student of physiology, for reaction means much more than muscle activity in any attempt to discover what constitutes a “normal working of the postural mechanisms.” (Alexander, F.M.; The universal constant in living, Chaterson L.t.d., 1942, third edition 1947, p. 112)

- “My experience as a teacher of the technique is derived from demonstrating daily to every one of my pupils that there is a primary control of the use of the mechanisms of the self, and that in taking full advantage of the influence for good in correctly employing this primary control we hold the key to the bringing about of the “normal working of the postural mechanisms” as a whole. (Alexander, F.M.; The universal constant in living, Chaterson L.t.d., 1942, third edition 1947, p. 115)

- “Co-ordinated use of the different parts during any evolution calls for the continuous, conscious projection of orders [of movements] to the different parts involved, the primary order concerned with the guidance and control of the primary part of the act being continued whilst the orders connected with the secondary part of the movement are projected, and so on, however many orders are required (the number of these depending upon the demands of the processes concerned with a particular movement)

Leave A Comment