Why are the orders of movements changing (all the times)?

Recently, Student “I.” renewed her lessons after a year without contact with me. She found that I requested her to change a series of orders of movement I had given her to project previously in an activity of readjustment designated to assume a position of mechanical advantage.

Here is the question she sent me a few days after visioning the video recording of the long-distance session she had done with me.

Answer Jeando M., Initial Alexander technique 20191218

Experimental failures as a spur to new discoveries

The lessons of conscious guidance and control are about directing the movements of all the different parts of the torso and limbs according to a plan both explicit and detailed in a series of verbal instructions (Orders or Directions of movements). Without realising it, very often, we are not doing what we think we are doing when we project a series of concerted intentions of movements, altogether, one after the other.

First, I give you some psychomechanical problem to solve. The psycho-mechanical problem always involves for its solution the question of how to translate some instructions (of movements of different bony parts) into a coordinated activity. You start learning the instructions and to project them in your activity. The plan is for example (it is the case we are discussing) to become capable of widening the distance between the Upper-Part-of-the-Arm spots & to raise the upper torso away from the lower torso while the shoulder-blades and arms are moving down. This involves a sliding motion of the torso Up along the interior of the Armpits and a reverse sliding motion of the arms Down against the torso (against the upper thoracic cage). As the ribcage is shaped as a dome at its upper extremity and as the shoulder-blades are linked by a belt of strong elastic tissues resting on top of the dome, when the dome moves upward, it tends to support (push) the scapulas upwards with a wider circumference, therefore the movements of widening and sliding are interdependent.

Then, as a second phase, we start analysing the concrete movements you are projecting in accordance with the instructions you have in memory. The relative disposition of the parts at the end of your performance (after your conscious projection of the intentions of movements during two seconds) is compared with the geometrical result obtained by F.M. Alexander when he was manipulating a student.

Let’s say that your different attempts at performing the instructions are not producing a coordinated result in accordance with the plan which can be inferred from the F.M. Alexander’s film. The idea of using the directions of the movements of the upper arms (through a conscious movement of the Tip of the Elbow spots) in opposition with the movements of the upper thoracic cage (upper torso) is also to pull the upper torso Forward relatively to the lower and middle torso which movements are directed Back (in opposition with the movement of the upper torso that is following the movement of the upper arms Forward.

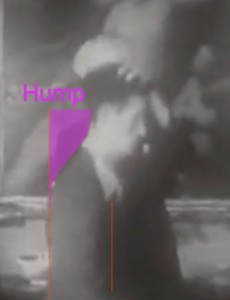

In summary, I am saying that we want to experiment whether it is possible to oppose the movement of the upper torso to the movement of the upper arms in the vertical and lateral directions, while to make them synergic in the Forward direction against the movement of the lower and middle torso. In theory this would tend to produce a dynamic “position” (we should say a dynamic geometry) with the Hump that is seen on the film above and, if the upper parts of the arms are moving away from one another, a new capacity of expansion of the ribcage under the armpits.

If the Upper-Part-of-the-Arm spots are not moving forward and outward relatively to the middle torso at the end of the concerted readjustment, there is little chance to see

-

the upper torso move forward relatively to the middle torso and

-

the “lengthening” which projects the Head Forward and Up and the back Back in opposition.

This opposition of movements (antagonistic action) and the resulting shape of the “Hump” is not seen in your experiments. The absence of this consequence in your projection of the orders brings about a need to make new experiments to understand why your self-manipulation, i.e. your translation of the orders (intentions of movements) in practice, is not showing the same readjustment as the one resulting from F.M. Alexander’s manipulations.

You ask: “How would the effect be different from the old instructions”? The goal of the lesson is not to give you all the possible theoretical explanations but to give you a chance to experiment on your own and note the many differences which will result from the change in the sequence of orders.

There is a problem nonetheless. One way you could make a new experiment of conscious guidance fail is to convince yourself that no change should be possible when the sequence is changing. F.M. Alexander had lots of problems trying to explain what it means to keep an open mind in spatial problems. I will give it a go.

As you know, our plan has always been to project a series of orders of movements simultaneously. This is our intention. Yet, when we control any experiment of conscious guidance by watching a video recording of the performance and look at the projection of a series of intentions of movements, we can see that the actual “physical” movements are not simultaneous nor properly “continuous” at any moment.

Some movements appear first, then this primary projection ends and is replaced by others projections of an intention of movement. Often a third movement which should be projected at the same time is not visible at all.

Analysing such experiments of conscious guidance, you could realise that the “easiest” movements (closest to your habitual, unthinking way of doing things) will always appear stronger, faster than movements that are contrary to your habits, and which tend to not appear at all. Inversely, because the latter, the “contrary movements” involve somehow both a stronger intent on your part (you need to find the resolve to project an intention of a movement that has no correspondence in our feeling register) and a decision to accept feeling “wrong”, they may totally block the performance of the other, easier movements, when your intention is to explore the unknown. In both cases, the concerted projection will fail.

To come back to your lessons, we planned from the start to see a sequence of instructions performed in a simultaneous coordination, but reality-in-activity is there to be reckoned with. It may be necessary to reason from what we see of the performance to alter the parameters at our disposal, for example, to re-order the sequence of instructions when we project the intentions into a gesture. Indeed, to create a gesture on film that looks perfectly simultaneous, it may be necessary to think of projecting an intention first very quietly, then, continuing this first projection, to project a second progressively and then, continue the first two and project a third with a variation of the force and speed of attack. We must check on video to see whether the readjustment goes in the right direction or not.

Imagine now that you are successful, that is, you are seen on video projecting the movements at the same time: would it matter that you have to think one after the other to obtain the readjustment altogether? I do not think so. You would just have realised in your own practice that concerted intentions and coordinated movements are not the same thing and can work in a different time frame.

Another reason for the change in the sequence of orders is to open your mind to the complexity of the guidance of movements that are interdependent. Movements can be interdependent, but mutual dependence does not imply perfect parallelism in cause and effect or in spatial and time frames.

Leave A Comment