[one_full last=”yes” spacing=”yes” center_content=”no” hide_on_mobile=”no” background_color=”” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” background_position=”left top” hover_type=”none” link=”” border_position=”all” border_size=”0px” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” padding=”” margin_top=”” margin_bottom=”” animation_type=”0″ animation_direction=”down” animation_speed=”0.1″ animation_offset=”” class=”” id=””]

This a long article. I have provided a Table of Contents at the start of the article for modern impatient individuals so they can jump straight away to the Third Part: “The secret story of the Primary Control”.

- Reasoning is a painstaking skill

- Alexander’s Discipline of Mind

- The secret story of the Primary Control

- Where are we today?

Definitions of mystify, verb

- misrepresent.

- to render something obscure or unintelligible.

Reasoning is a painstaking skill

In the traditional training of the modern Alexander technique, the students are not taught to develop their verbal memory, nor to lay any other foundations to construct their reasoning level and reading skills. It is as if there was no need for simple mind tools and even less for professional mind processes like ‘close reading’[1] to explore the foundational books of the Alexander Technique.

Such mind tools are mandatory to study any other difficult and complex subject, but the Alexander textbooks are supposed to make an exception because a skilled teacher is allegedly able to explain instructions with his hands (through manipulations of the parts of the anatomical structure of the person asking the question). You will understand quickly that, in my view, hands-on teaching does not help students conceive, manipulate logic chains of arguments and understand carefully worked out ‘systems of concepts’ as the one proposed by F.M. Alexander.

In any event, is it necessary for a teacher or a teacher trainee to understand the theoretical basis of the Alexander technique? Is there a point in training one’s capacity of reasoning in a logical manner?

I think there is some truth in the theory that the absence of well-developed mind tools exposes the students to all kinds of mystifications, marketing propaganda, and abuse of authority by a far from enlightened ruling class.

As I hope to demonstrate with a new look at the definition of the concept of ‘primary control’ which will be substantiated in the third chapter of this paper with evidence from Alexander’s writings, this is not just an obscure problem of theory for the very few teachers interested in the history of the technique, but it may have an impact on the practice, the teaching of the technique and the training of our teachers.

Because of the prevalent primary control mystification, the students are not trained to think of more than one thing at a time and, therefore, at the end of their training, they lack the basic means to relate mental constructs logically; worse, they are trained to think about what they feel before and after they are manipulated or after they manipulate themselves, forming a habit of concentration which is a real poison for constructive thinking, the very well from which the Technique evolved.

I think it is doubly sad, because the standard of reasoning which one can only achieve through a real ‘discipline of the mind’ is required:

- not only to question repeatedly and to trace the meaning of the words and conceptions employed by F.M. Alexander through all his writings in order to understand his theory to enhance the practical side of the teaching,

- but also to ‘project multiple preparatory orders for the DOING of a dozen or more parts of an action’ in practice which, we will see later, is the theory that F.M. invented to change his use of the self.

The whole psycho-physical tendency of the person who believes that concentration is essential to success, and adopts and develops it as a practice in his efforts in different spheres of activity, is “to bring the mind to bear on one object.” This exactly fits the “end-gaining” principle, and is antagonistic to the “means-whereby” principle which calls for the ability to bring the mind to bear on a dozen or more objects if necessary, and which implies a number of things, all going on, and converging to a common consequence (continuous projection of orders). (Alexander, F.M., “*Constructive conscious control of the individual*”, Integral Press 1923, reprinted 1955, p. 167, “Projection of Orders”)

In terms of history, I will show that the discipline of mind which Alexander sustained all his life has never been part of the curriculum of our teacher training centers ever since he started the first training course. One may wonder why Alexander never thought to transmit to his students the means whereby to read his books and to open their minds to relational systems which imply a number of things, all going on, and converging to a common consequence. It seems he thought they were well equipped (when it is clear they were not); it is also possible that he did not understand the problem because it has been reported many times that he would get angry when the student wanted explanations on passages of the same books he instructed them to read every day as the best way to understand the work! Such questions would have been perfect to start laying down the foundations of a serious discipline of the reasoning mind.

I will try to show that Alexander’s Students have not been trained to build a strong use of the reasoning mind necessary to form a sound basis for understanding Alexander’s views on his technique and, for the same reason, that they may have lacked therefore the required control of the mental means needed to put in practice the technique he exposes as early as 1910 and as late as 1942. To achieve such a thing, I will take the example of the concept of primary control showing the difference between Alexander explanations and the modern view on it. We will see how Alexander students have put their reason to good use in misunderstanding and misrepresenting the central tenet of the technique of their renowned teacher.

I pursue also a goal farther away in time: I will slowly attempt to convince my readers that the training of the mind necessary among other things to practice and teach the initial technique, either to yourself or others, can be derived from dedicated work on the books, mostly because understanding and following appropriate logical relations lead to a higher level of reasoning and a greater agility of mind. Once you develop a constructive guidance and control of the mind in text work, it is easy to apply it to the strange procedures of the Technique which are described in the books (like for example ‘thinking in activity’ – Alexander, “the use of the self”, p. 36,).

Alexander’s Discipline of Mind

By ‘discipline of mind’ I mean the practice of training oneself to act in accordance with series of established rules and orders, which necessarily involves the capacity to maintain the rules and verbal orders in mind and to articulate them in the proper way. In the study of Alexander’s writings, the principle is the same as in the practice of guiding oneself even if the rules are different: one needs rules and procedures in reading Alexander, in order not to be fooled by the ingrained habit of simplifying or by the craving for speed and for a sense of belonging. As a rule, it is much easier and you will get much more Facebook support in the process, if you accept to think in the same way as your peers, but numbers is not the same thing as truth. Faced with the same choice, it seems that Alexander had no trouble choosing the narrow path leading to the top of the mountain.

Before reaching any summit, Alexander certainly continuously trained his verbal memory and his accuracy with words (he was able to quote from any of Shakespeare plays given only a cue of three or four words). His conscious control of memory certainly gave him a real advantage in thinking construction.

As a shakespearian actor, Alexander was trained to speak and instruct with accuracy, to analyze on a reasoned plan (Alexander, msi, p. 125[3]) the movements of the character he had to impersonate. Is there any doubt that this kind of training must have helped him when it became time to impersonate a new use of all the parts of his organism?

Also, I take it as granted that the massive amount of time he chose to spend writing to expose his theory must have trained his capacity to reflect and link appropriately together multiple ideas in order to :

- develop experimental procedures to check his hypotheses,

- reason with non-fuzzy logic on revolutionary subjects (I wonder which of our teachers nowadays could discuss the technique with an inquisitive mind like John Dewey’s), and,

- guide his movements as a whole, i.e. develop ‘a general system for the improvement of the entire physical economy by a just co-ordination and control of all the parts of the system’ (Alexander, msi, p. 7[4]).

I find it difficult to separate this kind of discipline of mind from F.M.’s achievement in teaching himself his technique.

Yet I know how much criticism his books have received from many modern Alexander teachers.

In the last twenty-five years, I have heard many comments about Alexander’s supposed difficulty with words. It is not straightforward to evaluate these comments at their just value because they came most of the time from readers who acknowledged their lack of practice with scientific treatises and their difficulty in reading Alexander.

At the same time, I do not remember having seen any essay or a book discussing in other than very generalized and nebulous terms the problems and pitfalls of Alexander terminology or any work which would trace precisely the use of keywords and themes in his books.

This is a very common and fruitful practice in the scientific literature, but nothing of the sort in our discipline. The books are deprecated, yet there is but nothing in the form of rigorous articles or books to sustain such judgment. All things considered, our community does not seem interested in producing anything of importance about Alexander’s ideas, to sort out and explain Alexander’s keywords, principles and procedures as described in his writings. I may be mistaken and if you know of such an article or book, please enter in contact with me.

In my STAT training, there was a weekly hour of reading of Alexander’s writings, and even sometimes an open discussion on the paragraph presented by a senior teacher acting as reader. Apart from this passive hearing, we received no formal training regarding how we were supposed to memorize, read and study these sentences. We were not taught any particular means whereby exploring the rich soil Alexander had made fertile.

Sometimes, in the training centers where reading Alexander is customary, the senior reader himself in these sessions has strong opinions about the books. Nevertheless, this does not help the students build their own tools of the mind to work with the text; rather this would tend to force the students to ‘believe’ or worse to ‘like’ or ‘dislike’ every word the teacher is saying: « this is it! » and « this is so outdated that we can skip this passage… ». Having been subjected to a strong opinion is not the same thing as developing your own reasoning and judgment with accurate words and clear references to the parts of the text where the proposed opinions can be justified or recused.

The same goes for ‘discussions’: have you ever witnessed such a talk where the participants are discussing words or principles for which they have formed no clear meaning, nor studied the construction of the meaning of the ideas in the author writings? Most of the time the students could not even remember precisely the sentence, let alone two sentences under discussion. Such ‘discussions’ certainly cannot accomplish the task of elevating students to even the most modest ideal of reasoning.

No superficial reading and thinking like such can ever replace the careful, sustained mind work with appropriate mind tools to analyze all the dimension of the text that every student must invest in order to understand ideas as rich and complex as the one that are littered in every book of F.M. Alexander.

Yet, without any training, any means-whereby and any incentive, how are the students to develop their understanding and their capacity to reason with accuracy? The disinterest for Alexander’s written theories nowadays displayed by most teachers can be traced back to the lack of mind-tools to explore the books that describe the process that he constructed without ever receiving a hands-on explanation. There is no problem with the individual students, it is clearly a problem of training of their reasoning mind.

Now is the time to bring some evidence that supports the idea that the lack of hands-on with the text has profound consequences on the training of our teachers and their capacity to reason on the theory of our art.

What is most alarming is the incapacity of teachers to read and have in mind a whole sentence or more than one sentence at a time and thereby, to follow Alexander’s construction of his reasoning. Let’s now start the not so secret story of the primary control to give you an example of this state of affairs that leads to absolute misunderstanding.

The secret story of the Primary Control

In his last book, the Universal Constant in Living, 1942, Alexander explains (Alexander, ucl, p. 6[5]) that

« in practice, this use of the parts, beginning with the use of the head in relation to the neck, constituted a primary control of the mechanism as a whole» […].

This is only the beginning of the sentence, but for the moment it is expedient to make a very partial reading to examine the point in question. We have here the ‘use of the head in relation to the neck’, the verb ‘constitute’ and the complement ‘primary control’, very close together.

This proximity –‘This use of the parts beginning with the use of the head and neck constituted a primary control of the mechanism as a whole’– is easily translated into the idea you are all familiar with, that “Alexander’s greatest discovery is the existence of the influence of the Head/Neck relationship on the self as a whole”.

Reflect a moment and judge: do you think that the beginning of this sentence explains perfectly the principle that the Head-Neck relationship represent the primary control of the whole use of the self ?

The problem is that Alexander never meant anything like that! He rejected this simple shortcut as a blatant mystification/illusion. With hindsight, one may wonder at the rogue spirit who started the charade. Alexander himself, of course, knew about this, well before his death. In a letter to F.P. Jones in 1945[6], he admits that there is a possibility to misinterpret the import of the head and neck relationship:

« I don’t see how they can misinterpret the head and neck relationship… There isn’t a primary control as such. It becomes a something in the sphere of relativity ».

It is not necessary to wonder who the pronoun ‘they’ refers to in Alexander’s letter – it may be some of his students, that is people knowing about the advertised head-neck relationship. It is also not necessary yet to go very much in the details of the strange letter he wrote to F.P. Jones:

« we always use the head and neck relationship when explaining to outsiders and find it works ».

I will come back to that later on. It is not necessary to dwell more on this here because the riddle about the Head-Neck relationship & the « something in the sphere of relativity » is easily explained and documented by a simple analysis of the textual evidence actually present throughout Alexander four books.

As we have started by considering the sentence in isolation, note first of all that the pronoun ‘this’ in ‘this use of the parts‘ that constitutes the primary control is yet undefined within the boundaries of this proposition. Alexander is talking of a use of parts defined elsewhere; he affirms in passing that such use “is starting with the use of the head and neck“, but he does not mention strictly here how the use of the parts is finishing and what it entails. The fact that this use begins somewhere is not sufficient for us to establish what this use is. We need to look farther than this sole proposition to understand Alexander’s definition of the primary control.

The famous sentence which I quoted to begin this simple close-reading regarding the ‘primary control’ appears in fact just after another sentence which defines perfectly the pronoun ‘this’ in our sentence (‘This use of the parts beginning with the use of the head and neck constituted a primary control of the mechanism as a whole’). Let’s put both sentences in the correct order and ‘in extenso’ this time:

The ‘First Sentence’ or “Sentence1” which is just before the one we started discussing is here:

Readers of The Use of the Self will remember that when I was experimenting with various ways of using myself in the attempt to improve the functioning of my vocal organs, I discovered that a certain use of the head in relation to the neck, and of the head and neck in relation to the torso and the other parts of the organism, if consciously and continuously employed, ensures, as was shown in my own case, the establishment of a manner of use of the self as a whole which provides the best conditions for raising the standard of the functioning of the various mechanisms, organs, and systems.

My introductory sentence is in fact the start of the ‘Second Sentence’ or “Sentence2” of the paragraph:

I found that in practice this use of the parts, beginning with the use of the head in relation to the neck, constituted a primary control of the mechanisms as a whole, involving control in process right through the organism, and that when I interfered with the employment of the primary control of my manner of use, this was always associated with a lowering of the standard of my general functioning. (Alexander, F.M., “The universal constant in living, Chaterson L.t.d., 1942, third edition 1947, p. 6)

In the first (introductory) sentence –“Sentence1”–, Alexander reminds the reader that in his preceding book, “the Use of the Self”, he experimented with various ways of using the different parts of his organism to improve his voice. In this sentence, the use of the head in relation to the neck is not the relation put forward, instead, Alexander invoke a multidimensional, composite relation including the relation between the head and neck and the torso and the relation of both to the other parts of the organism. We see that, in 1932, Alexander is describing ‘a general system designed for the improvement of the entire physical economy by a just co-ordination and control of all the parts of the system’ (Alexander, msi, p. 7[4]), exactly as he proposed in 1910.

Coming back to the simple, unique relation brought up in the second sentence (sentence2), when you read the Use of the Self with attention, it is impossible to miss the fact that Alexander describes very clearly the head-neck relation individual influence on his voice improvement:

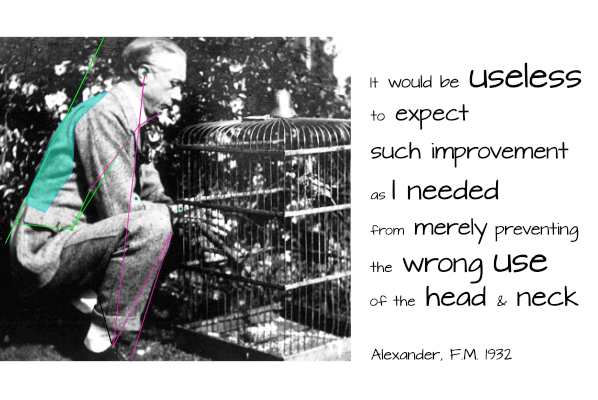

This new piece of evidence suggested that the functioning of the organs of speech was influenced by my manner of using the whole torso, and that the pulling of the head back and down was not, as I had presumed, merely a misuse of the specific parts concerned, but one that was inseparably bound up with a misuse of other mechanisms which involved the act of shortening the stature. If this were so, it would clearly be useless to expect such improvement as I needed from merely preventing the wrong use of the head and neck. » (Alexander, F.M., “The use of the self”, Integral Press 1932, reprinted 1955, p. 8)(Alexander, uos, p. 8[8]).

This sentence prepares the correct understanding of “Sentence2” and cannot be separated from it. When a component of the whole, i.e. the misuse of the head and neck, is “inseparably bound up with a misuse of other mechanisms” (Alexander, uos, p. 8) nothing allows us to conclude that changing the misuse of this component will change the whole misuse.

Alexander goes even further in the same line of thought to explain why merely preventing the wrong use of the head and neck relation is useless: if one attempts to change a specific misuse inseparably bound with a misuse of a greater number of parts, then the influence of the misuse of the greater number of parts will frustrate the attempts at consciously changing the specific misuse, and more misuse as a whole will be the result of the unreasoned effort.

It is important to remember that the use of a specific part in any activity is closely associated with the use of other parts of the organism, and that the influence exerted by the various parts one upon another is continuously changing in accordance with the manner of use of these parts. If a part directly employed in the activity is being used in a comparatively new way which is still unfamiliar, the stimulus to use this part in the new way is weak in comparison with the stimulus to use the other parts of the organism, which are being indirectly employed in the activity, in the old habitual way. (Alexander, F.M., “*The use of the self*”, Integral Press 1932, reprinted 1955, p. 13)

The fact that the use of the relation of the head and neck is inseparably bound up with a misuse of other relations does not lead to the possibility of change through a modification, conscious or otherwise (through manipulations), of the head and neck relationship. On the contrary, from that point on, Alexander imagines that the use of all the relations between all the parts of the system has to be consciously conceived and directed in order to change the whole and, indirectly, succeed in changing the specific part directly related to his problems of movement (speaking aloud is a movement which implies the movement of the different parts of the torso, neck, head and limbs down to the toes and fingers).

Change has to follow the path from the whole to the part (Alexander, ucl, p. xxxvi[9]),

i.e. it is by changing the system of relations between all the parts of the system that any fundamental change can be secured in one single relation between two parts. Translated in simple terms, this means

- that the simple mental order of inhibiting and directing the head-neck relationship is never going to change the use of the self, and,

- that the student must be trained to analyze, synthesize, and program movements of readjustment between all the parts to direct the whole system of relation all-together.

What Alexander has written here is that the system of relations between all the parts of the organism, the “general connected use”, is the “primary control” of the use of the self as a whole. But more than that, Alexander affirms that a new, reasoned system of relation between all the parts of the organism can be consciously and continually employed to establish a manner of use of the self as a whole.

… a certain use of the head in relation to the neck, and of the head and neck in relation to the torso and the other parts of the organism, if consciously and continuously employed, ensures, as was shown in my own case, the establishment of a manner of use of the self as a whole which provides the best conditions for raising the standard of the functioning of the various mechanisms, organs, and systems.

Real change cannot follow the path from the part (head-neck) to the whole (the use of the self as a whole). Of course, a subject of manipulations on the head and neck will report feeling many changes, but this has nothing in common with an improvement of the entire physical economy by a just co-ordination and control of all the parts of the system (Alexander, already cited, msi, p. 7). Alexander repeats the same thing in 1910, 1923, 1932 and 1942.

The fact that the whole system of relations between the parts cannot be conceived with sensory appreciation is a fundamental byproduct of this theory of conscious guidance. It is impossible to analyze a system of relations between parts of the anatomical structure as a whole with internal perception (lower cognitive function) because what our sensory system registers mainly is the difference between the new use and the habitual use and not the absolute value of a particular system of relations. A system of relations can only be conceived with the conscious mind, the reasoning mind, when it is directed in a rational way.

It is because of this recognition of a general connected use that Alexander started to form the concept of psycho-physical unity. The recognition of impossibility of a subconscious establishment of a wholesome general connected use is the reason why, in order to improve general use, the higher cognitive functions (controlled attention, voluntary memory, reasoning in systems with words and concepts) have to be organized in a new experience of ‘thinking’ to direct the will (Alexander, uos, p. 36) to manipulate properly the whole system of relation between the parts.

As I will develop Alexander’s idea, we will see that in order to improve his general use, the subject must name (stimulate his attention), have in mind (memory), manipulate (plan) many orders of movement of adjustments between the different parts of the organism & project (reason correctly) to subordinate his will to these directions and rules. The higher mental processes are therefore fundamental to plan and perform alltogether the physical movements of readjustment of the system of relations in front of a mirror in order to change the whole system of relations between all the parts of the anatomical structure. This is the root of the principle of psycho-physical unity.

The idea of relativity of the head and neck WITH the rest of the organism and in particular with the torso is not something new that Alexander invented in 1932. As soon as 1910, he writes that

« the specific control of the neck is primarily the result of the conscious guidance and control of the mechanism of the torso, particularly of its antagonistic muscular actions which bring about correct and greater co-ordination […]» (Alexander, msi, 1910, p. 126[10]).

This brings us back to the statement of the necessity to change use as a whole, that is, to consciously direct the system of relations between all the parts of the organism. It is better to let Alexander do the talking here:

I wish to make it clear that when I employ the word “use,” it is not in that limited sense of the use of any specific part, as, for instance, when we speak of the use of an arm or the use of a leg, but in a much wider and more comprehensive sense applying to the working of the organism in general. For I recognize that the use of any specific part such as the arm or leg involves of necessity bringing into action the different psycho-physical mechanisms of the organism, this **concerted activity** bringing about the use of the specific part. (Alexander, F.M., “*The use of the self*”, Integral Press 1932, reprinted 1955, Note p. 2)

Alexander has explained in simple terms that all the relations between all the parts of the system have to be consciously and continuously employed to establish a proper manner of use of the self as a whole. It is important to point out that this is written in 1942, near the end of Alexander’s career as a teacher, and there seems to be no change in the formulation of his central principle. In its core, the Alexander technique has not changed despite thirty two years of hands-on pedagogy.

The fact, almost always overlooked when the how of improving human behaviour is discussed, that a human being functions as a whole and can only be fundamentally changed as a whole. It is in the light of this fact that the technique described in this book has real significance. (Alexander, F.M., “Man’s supreme inheritance”, Chaterson Ltd 1910, reprinted 1946, p. vi, Introduction to the new edition, 1945)

Note that in sentence2 Alexander takes his own experience –of learning the technique without any ‘outside help’ providing a hands-on guidance– as evidence of the constructive capacity of an individual to consciously direct a system of relations between all the parts of the organism: “as was shown in my case, a certain use of the relations between all the parts can be employed continuously to establish a manner of use of the self as a whole”. This is interesting because Alexander makes this statement in favor of the autonomy of the pupil at the end of his life, after having promoted his hands-on pedagogy in many parts of his books.

“Sentence1” clearly indicates that Alexander is talking about a sphere of relativity, the same analogy he coined in his letter to Jones. A sphere has no starting point, no end point, but every point of the sphere is in RELATION to all the others. To change the influence of general use on a specific relation, the system of relations has to be consciously conceived, monitored and guided. This leaves open the question as to why Alexander has written in “Sentence2” that this use of all the parts of the system “begins with the use of the head in relation to the neck” when in fact he affirms that the control of the neck is a consequence of the control of relations of the mechanism of the torso. Could it be a way to remind the ‘outsiders’ of the often repeated explanation which works as he wrote in his letter to Jones?

What is most important here is the fact that, as was shown in his case, Alexander had found a procedural way to demonstrate that an individual can consciously direct his mind (intellect, memory and will) to become able to control the circular relativity between head and neck in relation to the relativity of the parts of the torso and the relativity between other parts of the organism without any reference to a correct feeling experience.

My own experience of teaching without hands-on led me to believe this part of the myth of the evolution of Alexander’s theory. Anyone wishing for a demonstration can take four or five long distance lessons with me and come to his own conclusions.

According to Alexander, it is this global direction and control of the general use of himself which improves the functioning and the manner of reaction of the self, and NOT the simple direction of the relationship between head and neck. To plan and perform these numerous relationships all-together, the individual must use language and reason because it is impossible to feel clearly four, let alone more than the twelve movements of adjustment at the same time that Alexander considers indispensable as means-whereby to establish the relations associated with good use of the self as a whole.

The point of interest in all these considerations lies in the fact that this prevalent belief in concentration goes hand in hand with the acceptance of the “end-gaining” principle, as against the principle of thinking out clearly and connectedly the means whereby an “end” can be secured, and of “bringing the mind to bear” on as many subjects (continuous projections of orders) as is necessary for the purpose. The whole psycho-physical tendency of the person who believes that concentration is essential to success, and adopts and develops it as a practice in his efforts in different spheres of activity, is “to bring the mind to bear on one object.” This exactly fits the “end-gaining” principle, and is antagonistic to the “means-whereby” principle which calls for the ability “to bring to bear on” a dozen or more objects if necessary, and which implies a number of things, all going on, and converging to a common consequence (continuous projection of orders). (Alexander, F.M., “Constructive conscious control of the individual”, Integral Press 1923, reprinted 1955, p. 167, “Projection of Orders”)

Language and reason cannot therefore be separated from the ‘physical co-ordination required to promote the functioning of the self’ because to think about all the parts at once and project the required relationships in the mirror (‘projecting the directions’), the habits of mind the untrained individual has formed of discontinuous attention and of haphazard and subconscious guidance and direction must be first attacked and broken (Alexander, ccci, p. 164[12]).

In passing, I mention that to conduct a close reading on Alexander sentences, the habits of mind the untrained individual has formed of discontinuous attention and of haphazard and subconscious guidance and direction must first be attacked and broken. If these habits are broken as a result of a practice of a concerted analysis of the text, it should be easier to learn the conscious guidance an control of the general use of the self.

According to this reading, inhibition, i.e. mastering a language of command to direct the mind away from thinking with the feeling sense and toward thinking in a system of relations between all the parts (conscious attention does not exist without instructions of conscious inhibition) is the first essential tool required to change a human being that functions as a whole and can only be changed as a whole.

Alexander continuously points to the fact that to carry out in ‘concerted activity’ many orders of inhibition and many orders of synchronized movements to realize the required relativity between the parts, the pupil must bring his mind to bear on the use of the self as a whole. The conscious guidance and control of the mind is required because the use of any specific part such as the neck involves of necessity bringing into action the use of the whole system of relations and it is only by changing consciously, i.e. by a reasoned direction of the mind, this system of relation that the head will be allowed to go forward and up.

Faced with this, I now saw that if I was ever to succeed in making the changes in use I desired, I must subject the processes directing my use to a new experience —the experience, that is, of being dominated by reasoning instead of by feeling, particularly at the critical moment when the giving of directions merged into “doing” for the gaining of the end I had decided upon. This meant that I must be prepared to carry on with any procedure I had reasoned out as best for my purpose, even though that procedure might feel wrong. In other words, my trust in my reasoning processes to bring me safely to my “end” must be a genuine trust, not a half-trust needing the assurance of feeling right as well. (Alexander, F.M., “*the use of the self*”, Centerline Press (1990), page 36).

Building trust in the reasoning processes to bring the student safely to his end is the definition of teaching in any sphere of activity and it is the great gift that the initial Alexander technique has to offer.

This is the purpose of his teaching: to teach the mind, or, as he phrases it, to develop a constructive conscious control of the mind in order to guide the will not by what one feels, but in a rational way with a connected series of directions designed to organize movements of adjustment in such a way as to establish a new connected system of relations between the parts.

As I said earlier, I believe that the proof of the soundness of his theory comes both from its theoretical consistency and from the fact that in practice, he became able to direct with verbal instructions and mirrors the general use of himself with all its relativity and as a result, to improve his functioning and manner of reaction as a whole.

Where are we today?

All this individual mastery in thinking and resultant success in practice is followed by the advent of the modern Alexander technique. After all these years, what is left of the trust in the reasoning processes? I am afraid that the complete disregard for the textbooks has completely disfigured Alexander discovery of the ‘integrated working of the organism’ and the conscious guidance and control of the use of the self.

But the time came when I saw that the defects in my reaction at a given point, which I and my advisers had tried to change by direct method and treatment, were not primarily due to defects in the use and associated functioning of the parts of the mechanism seemingly most immediately concerned (in my case the vocal organs [in the head and neck]), but were the indirect result of defects in my general use of myself which were constantly lowering the standard of my general functioning and harmfully influencing the working of the musculature of the whole organism. The processes of use and functioning, and which worked as I saw from the whole to the part, was sound evidence to me of an integrated working of the organism. (FM Alexander, “The universal constant in living”, Chaterson LTD, reprinted 1947, page xxxvi)

When I look at the situation from a higher perspective, I continue to fail to understand how it could have happened so thoroughly.

We have a man that finds out by himself that his problem of voice is not a consequence of the coordination of the parts seemingly most immediately concerned (the head and neck), but is an indirect result of defects in his general use of himself[14], including the torso and the limbs (remember that he found that his habit of grabbing the floor with his feet, a part not immediately concerned with speaking aloud, was strongly connected to his tendency to pull the head back).

How could he be betrayed in theory and practice with the primary control fake without none of his disciples to raise a voice of protest?

How could our teachers as a group (society of teachers) start to profess the idea that the general use of the self could be modified by an intervention on the head and neck relation? How could they come to think that hands-on teaching would ever be sufficient to train the pupils to develop a constructive conscious guidance and control of the system of relations of the self as a whole?

A possible answer is frightening and simple.

Remember that Alexander explained to F.P. Jones that the head and neck relationship was used to explain [nowadays we would say: ‘to sell’] the technique to ‘outsiders’ (« we always use the head and neck relationship when explaining to outsiders»).

« I don’t see how they can misinterpret the head and neck relationship. People understand the effect of different positions and, for instance, that with the horse, the fixed reins interfere harmfully with the efficiency in going up a hill in particular. We always use the head and neck relationship when explaining to outsiders and find it works. There really isn’t a primary control as such. It becomes a something in the sphere of relativity ». (Murray, A., D., “ALEXANDER’S WAY Frederick Matthias Alexander, In His Own Words and in the Words of Those Who Knew Him”, 2015, Alexander Technique Center, Urbana.,, p. page: 124)

Explaining to outsiders has become explaining to insiders, and the simplified marketing idea has belittled the theoretical breakthrough patiently constructed in all Alexander’s books.

The oversimplified idea of the primary control has also steered the research for the efficiency of the Technique miles away from the development of the discipline of the mind that could lead to its rebirth: as a symptom of this drift, I take the fact that the most active subjects related to the AT nowadays are ‘somatic’, ‘embodied cognition’, and “Ends” (measure of physical consequences of lessons), i.e. the antithesis of conscious guidance and control.

I understand that the concept of conscious guidance and control of the general use of the self by means of ’a connected series of preliminary acts guided by a connected series of instructions (‘directions’) (Alexander, uos, p. 38[15]) is less appealing to the general public –the outsiders– than the recurring dream of the magic of one simple relationship between the head and neck supposed to solve everything.

But how could all the ‘insiders’ miss the marketing imbroglio? It may be that no one expected that something constructive could come out of the years of work Alexander put in writing his books, or, better, that no one had the tools to conduct a close reading of these wonderful texts. The verbal tradition from individual teachers to students has extinguished Alexander’s herculean reasoning.

This is to say that the reasoning I have conducted here is only based on the books. I just traced the theory of the primary control through the four books; all was in there without fail. The truth was not hidden in double meanings and Alexander’s explanations are written in plain words and developed in all four books unfolding the global approach. I have just outlined the old initial definition of the ‘primary control’. I will expand the same work on the concepts of ‘means-whereby’ and ‘mechanical advantage’ and you will see that the work on the text will harvest as much dangerous fruits if not more.

It is possible that the modern theory of the primary control is the consequence of both the herd instinct and the lack of development of the reading/reasoning skills of the individuals; both mental habits favored the marketing of the Technique instead of the principles written in the books. Simplicity has replaced true reasoning. What was offered for reconstruction by analysis and synthesis from entirely reasonable propositions that can be demonstrated in pure theory and substantiated in common practice[16] has been neglected with the pretext that it was ‘intellectual’. The modern Alexander technique has lost man’s supreme inheritance of conscious guidance and control, and the teaching has lost its revolutionary impetus because it is at least ‘part intellectual’.

The process of ‘thinking in activity’ with its new experience in thinking[2] required for planning and performing a connected series of preliminary movements has been relegated to the museum.

Now if we are to understand the “ means-whereby ” principle on which the teacher who adheres to the idea of unity in the working of the human organism will base his teaching method, we must recognize that the attainment of any desired end, or the performance of any act such as the making of a golf stroke, involves the direction and performance of a connected series of preliminary acts by means of the mechanisms of the organism, and that therefore, if the use of the mechanisms is to be directed so as to result in the satisfactory attainment of the desired end, the directions for this use must be projected in a connected series to correspond with the connected series of preliminary acts. (Alexander, F.M., “The use of the self”, Integral Press 1932, reprinted 1955, p. 38)

Teaching has become more and more the transmission of an experience, a search for a disappearing fragrance of magic. The first generation teachers trained by Alexander were gifted with ‘extraordinary’ hands as a result of their improved general use & a strong connection between their hands and torso constructed by a solid employment of procedures like the hands-on-the-back of a chair. Yet, as time went on and because the hands-on experience is no guaranty to enable the pupil to think connected series of movements intended to modulate a system of relations between the parts, the general use of their disciples became brittle, and the magic started to decline. Paradoxically, this may have led to even more dedication to hands-on teaching and learning. Hands-on teaching capsulize the modern Alexander technique we know of today. This concentration on the ‘real way of teaching’ has led to a neglect of the principles.

There are also consequences for the absence of experience at wielding essential tools of the mind in our world of information where the contacts with the ‘public’ and ‘scientific world’ are so easy and participate to the impression we leave behind our track.

Teachers are quite happy to know next to nothing of the different theories — the theory of the principles and the theory of teaching with the hands– exposed in F.M.’s books because they have been made to believe either that ‘everything’ is contained in the modern pedagogy of the Alexander technique or that the modern hands-on technique is way better or enhanced in comparison with the initial (mis-guided?) efforts of the founder.

Another problem of reasoning is creating havoc. Many have been led to think and repeat that thinking-with-the-hands has nothing to do with ‘ordinary thinking and reasoning’. After the death of F.M., the technique has really become something that one should not reason but experience (Peter MacDonald, 1986[17]).

Excessive trust in thinking and reasoning might be an impediment on the path to truth and, in my experience, teaching intellectuals is not necessarily easier; they assume they know how to learn but often they do not, as they find it difficult to stop their reasoning to allow instead for a completely new and unknown experience to take place. (MacDonald, P.J. « Introduction to the 1987 edition of Man’s Supreme Inheritance », p. viii).

I do not remember finding any refutation of this extraordinary outcry. Yet the consequences of such reinterpretation are far-reaching. It leads to a situation where to think-and-reason is a completely different affair depending on which side of the frontier with the outside world you are. Alexander certainly would not have approved because he never wanted his technique to be entrenched in a pre-intellectual camp and defended as a mystical cult. He wanted his technique to be seen as a means to ‘develop our thinking and reasoning processes to produce phenomena which can be tested according to strict scientific method’[18].

This growing divide between the uses of reason outside of the AT world and inside it leads also to frigid stand-offish behaviour[19] perceived as a superiority complex on the part of the teachers in public media discussions. This behaviour of teachers appears spontaneously on the social media every time someone wants to understand the intellectual basis of our work. This intellectual position can be condensed in this way: “You have not experienced the right feeling (through appropriate hands-on) and feelings cannot be explained with words, so you cannot understand the magic of embodied cognition as we do”.

One of my pupils commented about the necessity to question our thinking on a public-media discussion quoting Heidegger:

The most thought provoking thing in our thought provoking time is , that we are still not thinking. Martin Heidegger

and was immediately and ‘gently’ attacked by a teacher replying that he certainly did not need Heidegger to think. This paper as well as the work this pupil is exploring with me make this question worth asking.

At the same time, I have noticed that many senior teachers who happen to be questioned by someone raising a theoretical question based on F.M. exact writing will interpret the question as a scolding, an attack or mean criticism. There is every chance that he will respond in kind or not respond at all. You must believe I have had this experience!

In these days when everybody agrees on the fact that the AT is losing ground, the numbers of students dwindling every year, the teachers having more and more difficulty to stand out against all the ‘well-being new age somatic’ offers, it may be time to change and to examine the mystified version of the primary control.

The general impression we project (2016) as a body of practitioners is that our intellectual field is settled, that Alexander’s theoretical legacy is done and fixed, and that everything is now clear and theoretical discussions are behind us. If a question is raised, it is dealt swiftly by the self-appointed watchdogs who defend the main political consensus dictated by Alexander’s followers in the 1960s. This is very far from « the strict scientific method » which is based on the criticism of theoretical hypotheses through new procedures. How many new procedures have you heard of in the last decade?

In the absence of clear theoretical basis and corresponding theoretical skills to explain it, the AT has lost its unique distinctive asset: “conscious guidance and control”.

The problem as I see it, i.e. the modern AT is totally oblivious to the need to consider the means-whereby the students could train their mind to reason with words at a higher level, when phrased in that manner, leads to a possible solution. We need to start to think about teaching the basic discipline of the reasoning mind, to our students as well as to our pupils. This is why I am going to use this blog as a teaching ground for the ordinary mind. I have come back full circle to the motto written on the young F.M. business card: “Thy Mind a Kingdom is“. The poem goes on like this: “For what You lack, your Mind supplies” and I add, when the mind is directed in a rational way.

I will continue to write about Alexander’s ideas in his books, and I will give an account of what they are and how one can start to work with “difficult” sentences and “difficult” procedures alike. I will also present new procedures based on research into the capacity of verbal orders of movement to imprint a change in a geometrical system of connected relations between the parts of the organism. As I have said, these psycho-physical procedures can be used to test the theory I have resurrected here.

All the best,

In Gabian, France, the 3rd of October 2016.

Initial Alexander technique, “Still fighting the tyranny of sensations”.

- I recommend to any student of a training course to listen to the two brilliant introductions to ‘close reading’ that Professor Gregory B. Sadler gives his students. Close reading by Gregory B. Sadler

↩ - The process I have just described is an example of what Professor John Dewey has called “ thinking in activity,” and anyone who carries it out faithfully while trying to gain an end will find that he is acquiring a new experience in what he calls “ thinking.” My daily teaching experience shows me that in working for a given end, we can all project one direction, but to continue to give this direction as we project the second, and to continue to give these two while we add a third, and to continue to keep the three directions going as we proceed to gain the end, has proved to be the pons asinorum of every pupil I have so far known. The phrase “ all together, one after the other ” expresses the idea of combined activity I wish to convey here. (Alexander, “the use of the self”, Centerline Press (1990), page 36).

↩ - It seems also to me that practice so called is so rarely directed by a reasoned analysis on a reasoned plan. Nor does the teacher analyse and instruct with accuracy. He demands from the pupil merely imitative, not reasoned acts. This makes practice so often futile for the imperfectly co-ordinated person, and teaching both halting and inadequate. (Alexander, F.M., “Man’s supreme inheritance”, Chaterson Ltd 1910, reprinted 1946, p. 125)

↩ - Where I use the words physical culture, currently and without a hyphen, I denote a general system for the improvement of the entire physical economy by a just co-ordination and control of all the parts of the system, particularly excluding any method which tends to the hypertrophy of any one energy without regard to the balance of the whole. (Alexander, msi, p. 7)

↩ - I found that in practice this use of the parts, beginning with the use of the head in relation to the neck, constituted a primary control of the mechanisms as a whole, involving control in process right through the organism, and that when I interfered with the employment of the primary control of my manner of use, this was always associated with a lowering of the standard of my general functioning. This brought me to realize that I had found a way by which we can judge whether the influence of our manner of use is affecting our general functioning adversely or otherwise, the criterion being whether or not this manner of use is interfering with the correct employment[7] of the primary control.

- In a letter to Frank Pierce Jones in 1945, he cautions Jones about a too fixed understanding of the primary control. « I don’t see how they can misinterpret the head and neck relationship. People understand the effect of different positions and, for instance, that with the horse, the fixed reins interfere harmfully with the efficiency in going up a hill in particular. We always use the head and neck relationship when explaining to outsiders and find it works. There really isn’t a primary control as such. It becomes a something in the sphere of relativity ». (Murray, A., D., “ALEXANDER’S WAY Frederick Matthias Alexander, In His Own Words and in the Words of Those Who Knew Him”, 2015, Alexander Technique Center, Urbana.,, p. page: 124) ↩

- When in my writings the terms “correct,” “proper,” “good,” “bad,” “satisfactory” are used in connexion with such phrases as “the employment of the primary control” or “the manner of use,” it must be understood that they indicate conditions of psycho-physical functioning which are the best for the working of the organism as a whole. (Alexander, F.M., “The universal constant in living, Chaterson L.t.d., 1942, third edition 1947, p. 6) ↩

- This new piece of evidence suggested that the functioning of the organs of speech was influenced by my manner of using the whole torso, and that the pulling of the head back and down was not, as I had presumed, merely a misuse of the specific parts concerned, but one that was inseparably bound up with a misuse of other mechanisms which involved the act of shortening the stature. If this were so, it would clearly be useless to expect such improvement as I needed from merely preventing the wrong use of the head and neck. » (Alexander, F.M., “The use of the self”, Integral Press 1932, reprinted 1955, p. 8) ↩

- The processes of use and functioning, and which worked as I saw from the whole to the part, was sound evidence to me of an integrated working of the organism… (Alexander, F.M., “The universal constant in living”, Chaterson LTD, reprinted 1947, page xxxvi) ↩

- The specific control of a finger, of the neck, or of the legs should primarily be the result of the conscious guidance and control of the mechanism of the torso, particularly of the antagonistic muscular actions which bring about those correct and greater co-ordinations intended to control the movements of the limbs, neck, respiratory mechanism, and the general activity of the internal organs. [emphasis added] (Alexander, msi, The Processes of Conscious Guidance and Control, p. 126) ↩

- The point of interest in all these considerations lies in the fact that this prevalent belief in concentration goes hand in hand with the acceptance of the “end-gaining” principle, as against the principle of thinking out clearly and connectedly the means whereby an “end” can be secured, and of “bringing the mind to bear” on as many subjects (continuous projections of orders) as is necessary for the purpose. The whole psycho-physical tendency of the person who believes that concentration is essential to success, and adopts and develops it as a practice in his efforts in different spheres of activity, is “to bring the mind to bear on one object.” This exactly fits the “end-gaining” principle, and is antagonistic to the “means-whereby” principle which calls for the ability “to bring to bear on” a dozen or more objects if necessary, and which implies a number of things, all going on, and converging to a common consequence (continuous projection of orders). (Alexander, F.M., “Constructive conscious control of the individual”, Integral Press 1923, reprinted 1955, p. 167, “Projection of Orders”) ↩

- It follows that an imperfectly co-ordinated use of the human organism is not associated with the broad, reasoning attitude and the accruing benefits just indicated. And as most people have developed a more or less imperfectly co-ordinated use of the mechanism, which involves reliance upon the “ end-gaining ” principle, it is not surprising that so many pupils have the habit of projecting unconsidered and disconnected orders —orders, that is, that have not been reasoned out from the point of view of the co-ordinated use of the different parts concerned, and which therefore result in a mal-co-ordinated movement. When, therefore, such a pupil comes for remedial work on a plane of conscious control, and is asked to project a series of connected orders continuously, he naturally finds great difficulty in breaking the habit he has formed of discontinuous attention and of haphazard and subconscious guidance and direction. In fact, it will be found that, as a rule, a pupil has no conception of linking up the different parts of the movement and the orders relating to these. He may, as I say, give the primary orders or directions required for the first part of the movement, but, as soon as that point is reached, he no longer attempts to carry on the primary order in association with that required for the secondary part of the movement, although the essential connexion between these two parts may be pointed out to him over and over again. The chief reason is that he believes that he cannot “ bring his mind to bear ” on more than one point at a time. As he expresses it, “ I cannot think of so many things at once.” (Alexander, F.M., “Man’s supreme inheritance”, Chaterson Ltd 1910, reprinted 1946, p. 164–165) ↩

- The fact, almost always overlooked when the how of improving human behaviour is discussed, that a human being functions as a whole and can only be fundamentally changed as a whole. It is in the light of this fact that the technique described in this book has real significance. (Alexander, F.M., “Man’s supreme inheritance”, Chaterson Ltd 1910, reprinted 1946, p. vi, Introduction to the new edition, 1945) ↩

- But the time came when I saw that the defects in my reaction at a given point, which I and my advisers had tried to change by direct method and treatment, were not primarily due to defects in the use and associated functioning of the parts of the mechanism seemingly most immediately concerned (in my case the vocal organs [in the head and neck]), but were the indirect result of defects in my general use of myself which were constantly lowering the standard of my general functioning and harmfully influencing the working of the musculature of the whole organism. The processes of use and functioning, and which worked as I saw from the whole to the part, was sound evidence to me of an integrated working of the organism. (FM Alexander, “The universal constant in living”, Chaterson LTD, reprinted 1947, page xxxvi) ↩

- Now if we are to understand the “ means-whereby ” principle on which the teacher who adheres to the idea of unity in the working of the human organism will base his teaching method, we must recognize that the attainment of any desired end, or the performance of any act such as the making of a golf stroke, involves the direction and performance of a connected series of preliminary acts by means of the mechanisms of the organism, and that therefore, if the use of the mechanisms is to be directed so as to result in the satisfactory attainment of the desired end, the directions for this use must be projected in a connected series to correspond with the connected series of preliminary acts. (Alexander, F.M., “The use of the self”, Integral Press 1932, reprinted 1955, p. 38) ↩

- “It is my belief, confirmed by the research and practice of nearly twenty years, that man’s supreme inheritance of conscious guidance and control is within the grasp of anyone who will take the trouble to cultivate it. That it is no esoteric doctrine or mystical cult, but a synthesis of entirely reasonable propositions that can be demonstrated in pure theory and substantiated in common practice. (Alexander, F.M., ”Man’s supreme inheritance“, ”Preface to New Edition“, p. xii) ↩

- Excessive trust in thinking and reasoning might be an impediment on the path to truth and, in my experience, teaching intellectuals is not necessarily easier; they assume they know how to learn but often they do not, as they find it difficult to stop their reasoning to allow instead for a completely new and unknown experience to take place. (MacDonald, P.J. « Introduction to the 1987 edition of Man’s Supreme Inheritance », p. viii). ↩

- This result [the improved condition of psycho-physical functioning] does not come about by inducing self-hypnotism, or because of some chance happening, as, for instance, the coming into contact with an outside influence, personal or otherwise, or the possession of some natural aptitude (habitual reaction) which is fitted to produce a certain desired result. In all these cases instinct rather than the thinking and reasoning processes is relied upon, whereas “ reasoning from the known to the unknown,” as in my technique, depends upon the conscious employment of means that conform to biological, physiological, and other laws known to us; in which, also, the observation of phenomena in cause and effect can be tested according to strict scientific method, so that, as Dr. Dewey writes in his Introduction, “ the causes that are used to explain the consequences, or effects, can be concretely followed up to show that they actually produce these consequences and not others.” (Alexander, ccci, “Preface of the 1947 Ed.», p. viii). (Alexander, F.M., ”Man’s supreme inheritance“, Chaterson Ltd 1910, reprinted 1946, p. vii) ↩

- This stand-offish attitude is summarized under the pretense that « because you have not had the sublime experience I know, I cannot explain and you cannot understand, so discussing our ideas is beyond your capacity to understand it ». ↩

Hi Jeando,

Thanks for a stimulating piece. I’m wanting to respond, and time permitting I will do so. However, despite your intoning in the direction of ‘reason’ and proper engagement with text and please do not fall into the trap that you seem to be setting for other teachers: that of simplifying and misrepresentation: using inappropriate levers to make a point.

I did respond in a comment to a poster – (who represents your work, I think)….. that I didn’t think we needed Heidegger to teach us to think. That was not an ‘attack’, gentle or otherwise! Simply an opinion.

Looking forward.

Best wishes,

Alun

My apologies! The whole misunderstanding comes from my inability to post on facebook: the picture was meant only as a link to the article “The primary control mystification” that should have been attached to it. My pupil’s comment was appropriate because it related to the ideas I was developing in that text ‘that reasoning is not taught in our training centers’, when yours was only a comment to the picture! I was clear to me that my pupil had read the text, and I assumed that you had too!

What is funny here is that I was explaining that most teachers of the modern AT believe that ‘in our field, we do not need lessons in reasoning’ while my point is exactly opposite, that reasoning inside the technique and outside the technique is the same process and we certainly need to train ourselves in reasoning, at least to follow Alexander’s theory. I think that my pupil thought about Heidegger because of his comments on Aristotles regarding the relation between theory and practice, that ‘theoria’ is not detached from everyday activities and decisions, but rather totally at the root of it.

I sincerely believe that bridging the gap between theory and practice is more in need in our field than ever and to read Heidegger or other thinkers greater than us may open a whole new way to think the relationship between theory and practice. If you have the opportunity to read the article, keep in mind that it is only the first of a series in which I will expand reasoning on all Alexander’s concepts. I welcome your intent to comment: I have decided to broadcast my ideas as a target for criticism and discussion. I think that unless we reveal the intellectual basis of our work instead of banking on its ‘magical effect’, there is no way we can progress in constructive criticism. All the Best, Jeando Masoero.

Thanks Jeando, and sorry to delay getting back. Firstly, a few opening remarks. I disagree, but can’t prove the point that some teachers are or are not fans of FMA’s writing. I for one relish his very long sentences with multiple clauses. I see that as requiring, necessarily a sustained and wide attention. It’s not the only sort of attention, however useful it may be to get to grips with the theory of FM and to have conversations with other teachers….

I’m not sure either about citing anyone’s inability to reason like Dewey. I’m not Dewey, I’m me! Why would I want to believe the words of someone I had not met anyway? I don’t always believe my own words from one month to the next! That goes for FM’s word as well, though they resonate through practical demonstration, so I’m more inclined to wrestle with them from time to time…. They were both people demonstrating inconsistencies and reasoning (based on prior habit no doubt) and wishful thinking and perhaps plain old stubbornness.

What did it for me with the AT was to be shown, all those years ago how I was the architect of my own morass. I was lucky to have great lessons – all hands-on at the time – that showed me where I could be if I learned better how I was interfering (and to stop that interference) with my ‘primary coordination’. Over time we embody inhibition and attention, it’s there all the time, to greater or lesser degree and to the extent of our intention.

And it depends on your starting point for having lessons. I can’t imagine that just talking would have made such an impact on me, especially if Dewey had been presented as a model for learning to think – though I’m certainly tired of the ‘feeling -based’ takeover in some quarters of the AT. There’s no doubt about it. The devil is in the detail, but many people don’t have the incentive to look at them. Just look at the debates in the UK and US around Brexit and the forthcoming presidential election.

Secondly, and rather at randomly, I can’t understand why anyone would think that the head / neck relationship is THE key to improving the ‘primary control’ or the reliability of our use or conscious guidance, if you like. Working with a person in a hands -on capacity, we put our hands where they are needed, not necessarily on the head/neck. I tend to start with the feet these days, if I remember the patterns, say, of even the last couple of weeks’ teaching. I find that I can achieve rather an improvement in basic use by enlisting observations about simple balancing reactions. That’s another line altogether, but it’s also possible that Alexander misconstrued the initial reasons for his observed reaction patterns and started at his head rather than his feet. As I said, another line….but a valid one I think.

As to the continuous projection of orders, don’t you think that this is an essential concept for a teacher to master especially in activating a ‘global’ response in a student rather than just a local one. That is the skill of hands-on and to quote Maisel, is a kind of unique ‘resurrection of the body’ for many who have experienced this kind of skill at the hands of a good teacher. This may be lacking in certain areas of the teaching profession, and I know that some people get bored with it just at the point where they are starting to learn it.

Next point; what, particularly leads you to assume that FMA was the best example of his “Technique’. I’m curious about this. He certainly seemed very spritely in the film, but the picture of him on the beach reveals some interesting ‘relationing’ of parts that might reveal inconsistencies depending on your point of view. Just a picture I know, but there is no evidence of his perfection, as someone to copy or revealing a secret geometry…… just that he could get someone out of the chair with (great) skill. I’d be interested to learn more about this (important to you) aspect of your work and the Delsarte connection.

I don’t think that there is any sense of a fixed view of the mechanisms underpinning the AT, in fact, more a realisation that the old models are outdated and that to talk to people in other fields updating is required and being attempted. The work is living!I I could talk more on that, but it’s late and I have had less sleep this week than usual….so perhaps can continue again soon.

Best wishes, Alun

Here’s a little piece I wrote a while back, an exploration of giving orders continuously whilst eating your cornflakes, but without the geometrical precision, needless to say 🙂 also another on the problem of disunity in seeking unity…

https://freedominthought.wordpress.com/2014/11/26/cornflakes-dont-let-them-get-the-better-of-you-conscious-guidance-and-control-revisited/

It becomes a something in the sphere of relativity ».

Hi Jeando,

So glad you’ve started this blog! It keeps me from feeling that I’m about to accost your email box with yet another question about FM’s writings 🙂

It is my experience and understanding that to not think, question, close-read, or develop our mental thinking is to die creatively; of course to adhere to the fact that “thinking” is a lower activity because one has experienced the “hands” only leads to anarchy: reminds me of ayatollah khomayni and his “hand wave”: though shall not question!