Model based reasoning in the Alexander technique

This article arose as an answer to a question (below) of one of my young students. You will quickly see that there is more than just the requested answer as I continue to explain a) the form of reasoning Alexander was endorsing in his books and b) how this form of reasoning represents not only the springboard of his discovery but also the tool by which we can bring our pupils to radically change their conceptions about the use of the self, provided we train them to reason in this manner.

I personally think that training our pupils to reason and to reduce the gap between their speech and their actions is more important to their lives than improving their use of the self. Nonetheless, as improving general use and reasoning-in-a-new-way go together, it is clear that the fact that most people suffer from poor coordination and have no idea other than deceptive somatic methods of cure to alleviate their defects makes the subject of conscious concerted movements the perfect training ground for and introduction to model-based reasoning.

I will finish this introduction with a word of caution and encouragement. This article may be difficult to read; depending on your training, it may even feel hostile to many of your cherished ideas. In the following sentence, “The pupil who has been brought up on the subconscious methods is not attracted, as a rule, by this form of reasoning when faced with a “difficulty” (Alexander, F.M.; CCCI, p. 86), what Alexander meant by “subconscious methods” is what is known today as somatic culture, a culture which encourages sensing, a sensory perception that is proprioceptive self-sensing of the “body” by the ‘mind’ (Mullan, K.; The Art and Science of Somatics: theory, History and Scientic Foundations, (2012). Master of Arts in Liberal Studies (MALS). Paper 89. p. 11). If you have been trained by and if you support the subconscious methods, you should not be attracted to this reflexion (according to F.M.), because its subject is reasoning, the core of the principle of conscious guidance and control and because reasoning to solve coordination problems is directly opposed to somatic culture. Yet, I would like to encourage you to read on, as there is nothing better than discussing theories on which different practices are based to know your own.

“Know thy self, know thy enemy. A thousand battles, a thousand victories”. Sun tzu; the art of war.

Here is the question:

Q: Hello Jeando, one more question came up from the “to see or not to see, reflexion on pedagogical tools” article from the part “The battle of reasoning from visual clues against the ‘example and authority of touch'”: “When Alexander changed his general use (general coordination) he was working with his reflection (reasoning) while he was working with his reflexion (visuospatial cognition) in the mirror. These activities were not separated. He was not interested and even less guided by what he felt: he combated his self-hypnotic tendency with controlled experiments in which he ordered the movements of his reflection to see what he was really doing with the different parts of his torso. I cannot see why we should not do what he did in our lessons.”

Q: Could you please clarify the difference between the use of the words ‘reflexion’ and ‘reflection’ and why the latter can be understood as reasoning and the former as visuospatial cognition? I get most confused when you write that “he ordered the movements of his reflection”. It makes not much sense to me to substitute ‘reasoning’ in there. Hope you can clear this up for me!

What has become of the tool of inquiry, the Alexander technique described in 1917 by John Dewey?

With conscious control, on the other hand, true development (unfolding), education (drawing out), and evolution are possible along intellectual as against the old orthodox and fallacious [somatic] lines, by means of reasoned processes, analysed, understood, and explicitly directed. Conscious control enables the subject, once a fault be recognized, to find and readily apply the remedial process. (Alexander, F.M.; Man’s Supreme Inheritance (Third Ed., 1946), p. 137)

I am sorry to have created the confusion; yet you must understand that I first started it on purpose. The sentence “he ordered the movements of his reflection”, where “his reflection” means the image of the articulated segments of his anatomical structure shown by his mirrors[1] makes perfect sense if you realise that visual analysis reveals the movements of the different parts of the mechanism with which a person assumes his postures. The movements of the different parts represent the means whereby a posture is gained while the form or position (the type of relationship between the parts) represents the end.

“I don’t like the word posture, I don’t like the word behaviour and I used them as little as possible in my books. Posture is a static condition, it is the end to be gained, not the means whereby you should gain it. […]

“The point I am after is that I am interested in what you are doing with yourself in moving, for instance, your arm…” (Alexander, F.M.; St. Dunstan’s Lecture, 1949).

When working with himself, Alexander found he could “order” himself to do simultaneously different movements of each and every parts of the anatomical structure that he had seen on the mirror to obtain a new relationship between the parts in his reflection/image.

The method is based firstly on the understanding of the co-ordinated uses of the muscular mechanisms, and secondly, on the complete acceptance of the hypothesis that each and every movement can be consciously directed and controlled. (Alexander, F.M., “Man’s supreme inheritance”, Chaterson Ltd 1910, reprinted 1946, p. 120)

This became possible, only because he had used mirrors and the means of reasoned processes, analysed, understood, and explicitly directed. Seeing in his reflection/image what he theorised “wrong movements” or “series of habitual, unconsidered movements of the parts which had resulted in the deformation of the torso” gave him the opportunity to reason out a model of the mechanism he was dealing with to plan (to think about a future situation which was contrary to his habit of movements or habit of general use in order to decide the best way to do it) and experiment a new general coordination constructed with correct concerted movements of these parts explicitly directed by a series of verbal instructions.

He soon discovered that planning the orders and giving the orders of movement was only a necessary theoretical move with little effect in practice: more often than not, he failed to put his new decisions in practice because his sense of feeling was overriding the conscious series of decisions in his attempts at projecting the new use (at the critical moment when the giving of the orders of movement merged into “doing”).

Faced with this, I now saw that if I was ever to succeed in making the changes in use I desired, I must subject the processes directing my use to a new experience—the experience, that is, of being dominated by reasoning instead of by feeling, particularly at the critical moment when the giving of directions merged into “doing” for the gaining of the end I had decided upon. (Alexander, F.M., “The use of the self”, Integral Press 1932, reprinted 1955, p. 22)

This is how he came to devise a process of conscious guidance and control by which he could progressively make sure to obey his speech-instructions and not his feeling-sense, to bridge the gap between his speech (orders) and his actions, whatever his feelings during the projections of his intentions. You know the story of his combat against his subjective habit,[2] i.e., against his habit of judging whether experiences of use were “right” or not by the way they felt.

At least, this is what I had intended to do and thought I had done, so that, as far as I could then see, I should have been able to employ the new “means-whereby” for the gaining of my end with some degree of confidence. The fact remained that I failed more often than not, and nothing was more certain than that I must go back and reconsider my premises (Alexander, F.M.; The Use of the Self, Its Conscious Direction in Relation to Diagnosis, (Third Ed. Centerline Press 1946).pdf, p. 20).

Coming back to your question, it is also true that I added on the confusion in my conclusion by exchanging by mistake the role I had affected to the words reflection (visuospatial cognition) and reflexion (reasoning with speech). Since then, and thanks to your comment, I have overhauled the article. Of course Walter Carrington, from whose mouth the sentence is taken,[3] could not have made a) the same spurious distinction because he was speaking that sentence aloud and b) nor the error which conflicted with my demonstration (which you cleanly spotted out) .

So to set the account straight, according to Walter, Alexander, unlike the people he trained, used his REASONING to plan and order the movements of the parts of his anatomical structure he could SEE of his own image in the mirror and he was not interested in the feelings these movements produced. In other words, he was not interested in the old orthodox and fallacious lines which all taught movements relying on the feeling sense of the pupil. The reason he was not interested should be obvious: he had found in his experiments of guidance of a new general use that he could not use his sense of feeling to make sure that he had obeyed his new reasoned decisions “— either to refuse to give consent to an unwanted movement or to give consent to a new movement in the concerted series he wanted to coordinate.

Clearly, to “feel” or think I had inhibited the old instinctive reaction was no proof that I had really done so, and I must find some way of ” knowing” (Alexander, F.M.; The Use of the Self, Its Conscious Direction in Relation to Diagnosis, (Third Ed. Centerline Press 1946), p. 21).

I will come back in a moment to the emphasis on the ‘reasoning phase’ [reflexion] in the previous sentence and the relation with the ‘seeing phase’ [reflection] in his process of experiments.

First, lets say that he whole apparent confusion between reflection and reflexion was an error on my part which I made to alert the reader to a connection seldom recognized. I will explain.

You need to know that is possible to think the distinction between what you see in the mirror and what you reason very easily in French: In French, the word “le reflet” is the reflection of something on the mirror. It is purely a visual characteristic and has no connotation of reasoning. Again, in French, the word “la réflexion” is the capacity to think. It belongs primarily to the semantic field of ideas, logic and speech constructions. It can only become associated with visual cues when associated with a clause involving some ray of light being projected on a reflective surface.

In English, the nouns reflection and reflexion exist and are identical. They both mean a) the image of someone on a mirror and/or b) careful thought and consideration. Depending on the context, the reader will find which definition to use, whether the writer is observing his reflected image or observing his thoughts.

Now, knowing this, the distinction I made was a remote attempt at highlighting the close relationship between the two activities in Alexander fundational experiments and the benefit that can be gained in teaching our students to reason with prototypal models (model-based reasoning), starting with the models Alexander describes when he sees the movements of the different parts of his torso in the mirrors. Different models will illustrate the main characteristics and constraints of a mechanism[4] which can because of the representation of the model in mind be manipulated mentally with tought-experiments in order to guide decisions of concerted movements you have never done before and, hence, never felt beforehand. I will show that making decisions on the basis of this form of reasoning and mental manipulations based on a score of definite models was essential to Alexander conceptual change and ‘discovery’ and it is quite possible that it will reveal itself as a fundamental means to learning conscious guidance and control in the future.

This is to say that the subject is, to me at least, much broader than it seems at first glance. It touches WHAT we are teaching and how we could teach. Most modern Alexander technique teachers nowadays teach the technique as if it was some sort of somatic therapy (teaching their pupil to feel a ‘correct use’, i.e., a correct result), or, for the less orthodox, a technique to cast hand-spells on the pupil to produce a gentle form of spiritual healing. Placing the sensory experience of an organisation of different parts before its conception, they all reject reasoning as a form of “separation from nature”. They do not see a) that Alexander had to reason before he could conceive a new coordination, i.e., an orderly combination of the different parts of his organism, and b) that he gained a sensory experience of it only after having managed to make his decisions effective against his subjective habit.

As the reader knows, I had recognized much earlier that I ought not to trust to my feeling for the direction of my use, but I had never fully realized all that this implied—namely, that the sensory experience associated with the new use would be so unfamiliar and therefore “feel” so unnatural and wrong that I, like everyone else, with my ingrained habit of judging whether experiences of use were “right” or not by the way they felt, would almost inevitably balk at employing the new use. Obviously, any new use must feel different from the old, and if the old use felt right, the new use was bound to feel wrong. I now had to face the fact that in all my attempts during these past months I had been trying to employ a new use of myself which was bound to feel wrong, at the same time trusting to my feeling of what was right to tell me whether I was employing it or not. This meant that all my efforts up till now had resolved themselves into an attempt to employ a reasoning direction of my use at the moment of speaking, while for the purpose of this attempt I was actually bringing into play my old habitual use and so reverting to my instinctive misdirection. Small wonder that this attempt had proved futile !

Faced with this, I now saw that if I was ever to succeed in making the changes in use I desired, I must subject the processes directing my use to a new experience—the experience, that is, of being dominated by reasoning instead of by feeling, particularly at the critical moment when the giving of directions merged into “doing” for the gaining of the end I had decided upon.(Alexander, F.M.; The Use of the Self, Its Conscious Direction in Relation to Diagnosis, (Third Ed. Centerline Press 1946), p. 21)

I would like to show that there is another approach possible which, despite the fact that Alexander did not teach entirely that way, was clearly heralded in his writings. This other approach is to teach a process of inquiry, using model-based reasoning in order to make and maintain decisions of movements which are at variance with our habitual use of the different parts of the torso.

Despite John Dewey’s appreciation which places the Alexander technique as a scientific teaching in the strictest sense of the word, the modern Alexander technique has never been taught as principled teaching or, to take a more common expression, as a scientific subject, i.e., a tool of inquiry for the individual 1) to evaluate his decisions of concerted actions (concerted movements) and 2) to transform radically his attempts at changing his habitual coordination.

Any sound plan must prove its soundness in reference both to concrete consequences and to general principles. What we too often forget is that these principles and facts must not be judged separately, but in connexion with each other. Further, whilst any theory or principle must ultimately be judged by its consequences in operation, whilst it must be verified experimentally by observation of how it works, yet in order to justify a claim to be scientific, it must provide a method for making evident and observable what the consequences are; and this method must be such as to afford a guarantee that the observed consequences actually flow from the principle. And I unhesitatingly assert that, when judged by this standard—that is, of a principle at work in effecting definite and verifiable consequences—Mr. Alexander’s teaching is scientific in the strictest sense of the word. It meets both of these requirements. In other words, the plan of Mr. Alexander satisfies the most exacting demands of scientific method. (Dewey, John; in his introduction of Alexander, F.M.; Constructive Conscious Control of the Individual (Eighth edition, 1946).pdf, p. xxiiv)

It is not difficult to find in his books strong passages where Alexander considered both proposed subconscious practices (somatic therapy and spiritual healing) as “unreasoning ways to find a cure”, but his advice has been discarded and the damage has been done as it has been totally forgotten that the technique could be a tool of personal inquiry based on a form of reasoning unheard of in gestural and movements practices. As Norwood Russel Hanson remarked, when we are exposed to a radical new conception, “the issue is not to theory-using, but theory-finding“.[5] The main ordeal is not the testing of Alexander’s hypotheses but their re-discovery by each and every pupil which has lessons with me. Alexander saw different things in his mirrors and reasoned in a different way than somatic educators do, and there is no authoritarian way to make ourselves or our pupil see or reason the way he did. My way is to help the student construct his own path of inquiry, by teaching him how to use the tools which make reasoning with models possible, and thereby, construct his own experiments to form his own new conceptions.

Of course, there are obstacles to overcome or bypass. It is now impossible to talk about ‘reasoning’ and ‘teaching’ in the same sentence without having Alexander touch-teachers raise their shoulders to the sky. It has become inconceivable for trainees and pupils alike to envision learning and later teaching the technique as a form of science lesson —an everyday method of inquiry into their own gestures and reactions, i.e., a method of inquiry into the link between the orders they give themselves and how they respond to these orders. This approach does not seem, look or feel like the modern Alexander technique. It bypasses the need to rely on the pupil’s subconscous guidance, i.e., his ingrained habit of judging whether experiences of use are “right” or not by the way they feel; it rests on training the pupil’s mind 1) to reason about solving real kinematics problems on their own and 2) to inquire on how he can make his speech orders direct his decisions and actions in actual practice to create unknown experiences by reasoning from known to unknown experiences.

For years now the technique described in my book The Use of the Self has made possible the gaining of previously unknown experiences by reasoning from known to unknown experiences in the process of bringing about changes in manner of use (Alexander, F.M.; The Universal Constant in Living, (Third Ed. 1946), p. 161)

In my view, there is a great difference between teachers and therapists. “Teachers” teach their pupils to reason about problems they encounter and to construct their own appropriate experiment which lead to solutions, i.e., solutions appropriate to their needs, when therapists provide a fixed solution with their own hands!

It was a time when “reasoning” as in “reasoning from the known to the unknown“[6] was the distinctive feature that served to distinguish the Alexander technique. Nowadays, reasoning is totally discredited by the therapist-teachers themselves as they cannot understand the link between reasoning and conscious guidance of a complex anatomical structure. They do not see that reasoning can make possible the gaining of previously unknown experiences in the process of bringing about changes in manner of use (in series of concerted movements). They most of the times restrict the conception of reasoning to a cold intellectual play with deductive and inductive arguments after which it is easy for them to oppose that ‘reduced form’ of reasoning to the live, gleaming world of feelings they propose as proof of the efficacy of their ‘teaching’. Even the offshoots of the main churches of the modern Alexander technique which make some effort at analysing Alexander’s books have totally cut off reasoning from the practice of procedures: in the end, all their reasoning is to justify the use of the hands in teaching and the “need of sensory control” to learn and apply a new use.

I maintain that when Alexander teachers view themselves as ‘somatic educators’, they are missing the fact that the kind of reasoning Alexander was using —model-based reasoning— is nothing they imagine and that there is a great cost to pay for dismissing it so readily, i.e., losing the very core of the rational technique brought to us by F.M. Alexander’s books.

Apart from the initial Alexander technique, all the approaches of gestural education are somatic — modern Alexander technique, Pilates, Feldenkrais, dance education, Yoga, BodyMind centering, etc…— are all based on the same core principles, “natural movement”, guidance and control through “correct feelings”, concept that the pupil should think the “correct thoughts” to invoke some ‘inner intelligence of the body’, positive suggestions associated with light touch and all the like. Associating the Alexander technique with these methods which seek to reach the subjective mind and the natural body and to put the flexible working of the reasoning mind is just missing its revolutionary theory of conscious reasoned guidance and control.

Briefly, all three methods [hypnotism, faithhealing, repetition of positive orders] seek to reach the subjective mind by deadening the objective or conscious mind, and the centre and backbone of my theory and practice, upon which I feel that I cannot insist too strongly, is that THE CONSCIOUS MIND MUST BE QUICKENED.

It will be seen from this statement that my theory is in some ways a revolutionary one, since all earlier methods have in some form or another sought to put the flexible working of the true consciousness out of action in order to reach the subconsciousness. The result of these methods is, logically and inevitably, an endeavour to alter a bad subjective habit whilst the objective habit of thought is left unchanged. The teachings of the “New Thought” and of many sects of faith-healers set out clearly enough that the patient must think rightly before he can be cured, but they then set out, automatically, to carry out their teaching by prescribing “affirmatives” or some sort of “auto-suggestion,” both of which are in effect no more than a kind of self-hypnotism, and, as such, are debasing to the primary functions of the intelligence. (Alexander, F.M.; Man’s Supreme Inheritance (Third Ed., 1946).pdf, p. 31)

When Alexander insists that the conscious mind must be quickened, he certainly does not mean that we must teach our pupil to think quicker about what he feels or about what the should ideally feel instead: the modern pupil is already totally immersed in a feeling quagmire, devoting all his attention to what he feels, to his muscle sense and emotional unrest to the point that he is incapable to perform just two orders of movements when they conflict with his sensory appreciation and his habits of coordination. In this sense, suggesting that he should learn to fix his mind on some correct feelings that the teacher will provide is just so banal and unoriginal that the modern Alexander technique teacher will have all the trouble in the world to explain what it is that the pupil will find in his lessons that the other techniques do not offer.

Learning to reason with flexible models, learning to organize series of decisions and to maintain these decisions in the face of unpleasant experiences, learning to develop the incentive to conduct long term experiments, to delay gratification with ease, this is really what quickening the conscious mind means. The initial Alexander technique is offering NOT well-being, a result, but a domain where the person will be free to affirm and expand its own authority over herself by conducting reasoned inquiries to explore her own reactions and patterns of use.

An example of model-based reasoning

Let me give you an example of the need to take lessons of flexible reasoning and what models have to do with such endeavour.

I like answering questions about Alexander’s books from students of the training centers of the modern Alexander technique because it gives me an insight into their capacity to reason with simple models. Understand that when I am evaluating their reasoning, I am not judging them personally, I just evaluate how they are trained to think by their teachers and to make the link between words and actions. I do not provide final answers on their questions, I try to make them model their reasonings with clear guidelines.

This modelling is not just a personal crusade: I have always been amazed at the number of models of mechanisms Alexander has used in his books to construct his reasonings. The most astonishing in this is that no one seems to have reflected on his employment of models. They are just taken for granted and, for what I have seen, they are often dismissed as ancillary. Yet, when one starts to investigate, it is obvious that Alexander technique students do not understand how to reason with them: unwary readers just believe they understand at first glance what Alexander is writing about, when in fact they form the most striking misconceptions about them, and, more importantly, they fail to follow in the path of Alexander’s reasoning with the added windfall that they certainly fail to take his terminology seriously. This alone is sufficient to explain why the modern Alexander technique has gone so far away from the principle of conscious guidance and control.

This example will serve to show that without a meticulous deciphering, figuring out and assimilation of his models, it is impossible to understand Alexander terminology and manner of reasoning.

Here is an extract of a question & answer I had with a third year student last week (this student trains in a STAT teaching center 7000 km from France but has private long distance lessons with me). We are discussing a test I had him conduct based on an idea Alexander has written about regarding breathing-in, i.e., we are constructing a method for making evident and observable what the consequences of this written theory are. (In the transcript, I have stripped the technical jargon we use to direct the movements of the different parts of the structure of the torso)

Q: If the Serratus Anterior pulls the front ribs outward (and up) as well as moving the scapula outward (and down) to widen the upper back, isn’t this in contradiction to a previous lesson where I ordered a movement to bring the free ends of the lower ribs closer together?

A: The Serratus Anterior pulls the lower ribs upward and outwards (laterally) when nothing else acts on the ribs or on the shoulder blade. At the other extremity, the action of this same muscle pulls the shoulder-blades outward (widening the upper back), forward and down.

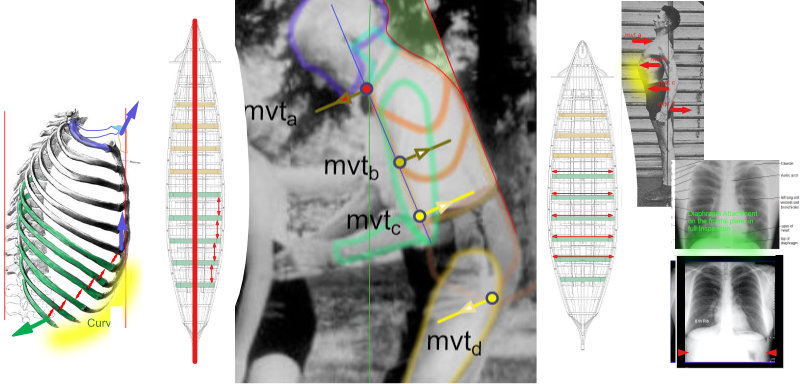

It is important to have an idea of the consequences which manifest themselves when this muscle is ineffective. When it is relaxed (out of action) the picture is rather striking.

This is a very common picture of a modern Alexander technique touch-teacher teaching the rest-cure to a pupil while giving consent to all the wrong movements which shorten her spine, narrow the back and fix the neck. The teacher is not aware of anything untoward in her coordination of the different parts of the torso for she has published this photo to promote the modern Alexander technique to the public at large (Photo taken from a internet website promoting the modern Alexander technique).

What this montage will show is that, with an ineffective, i.e., relaxed, serratus anterior muscle which has been put out of action[7] by the different decisions of movements that this touch-teacher has given consent to, the shoulderblade is protruding at the back, the lower back is hollowed, the lower ribs are not pulled back and up toward the shoulder-blade but sticking forward, the abdomen is protruding forward and the vertical curve at the lower ribs (in yellow on the diagram) is flattened. The diagram next to the picture of the somatic touch-teacher represents a relaxed serratus anterior: the shoulder blade is closest to the upper spine: the upper back is narrowed, the lower ribs are pushing forward and the top of the sternum is pushed back compromising the whole poise of the chest. The muscle is in a relaxed state (limp or flaccid) and does not contribute to the coordination of the different parts of the torso. The coordinated principles brought about by Alexander’s method are not established and it is clear that the teacher’s torso is shortened.

What Alexander proposes (actively preventing the lateral expansion of the lower ribs when breathing in)[8] is not a contradiction with bringing the serratus anterior back into action, it is the principle of antagonistic action in practice. Bringing the lower ribs closer together (lateraly) gives a firm anchorage to the portion of the serratus anterior that lifts the lower ribs —preventing the lateral widening of the lower ribs and letting the higher ribs lift up much higher— and allows the muscle to work at a much longer length[9] (instead of being shortened by the widening of the lower ribcage) to pull easily the scapulae outward, forward and down and maintain the lower ribcage and lower back back.

It is amazing to compare the image of the modern Alexander technique teacher with that of a student of the first training course (after just one year of training). The effect of the orders are unmistakable upon the whole mechanical mechanism of the torso of the student, when the modern teacher seems to have learned nothing about the coordinating principles brought about by the method. The student’s mechanism of the torso is not displaying all the correct relationships between the different parts, yet there is no question that she is going in the right direction.

“And the effect upon the whole mechanical mechanism of the person concerned is shown by the fact that when the coordinating principles brought about by this method are established, there is a constant tendency for the torso to lengthen, whereas the usual tendency—due to faulty standing position and the incorrect co-ordinations which follow—is for the torso to shorten“. (Alexander, msi, p. 168)

Q: I am asking because I sometimes am able to raise my torso quite high without the ribs coming closer together, but then something I am doing to bring them closer together makes me lower the torso again. Is there an optimal distance between the free ends of the lower ribs (like the fist measure with the 1st metatarsil head), or are they supposed to be as close together as possible?

A: No, I do not know of an optimal minimal lateral distance between the free end of the lower ribs: if you see on film that you lower the upper torso again after a certain shortening of the lateral length between the free ends of the ribs, there must be another movement that you are synchronising with it and it must be analysed so that the subconscious decision to give consent to that movement can be inhibited.

Q: My first question also brings to mind a passage in MSI that creates an analogy between increasing the distance between the free ends of the ribs to lengthen the spine and the ribs of a boat. This also seems in contradiction to bringing the free ends of the lower ribs closer together, but I can imagine an interpretation where it does not conflict.

“This play is effected in the human body (and would be effected mechanically in the ribs of a boat, if they possessed sufficient elasticity) by the coming together of the ends of the “false” and “flying” ribs- that is, those lower ribs which are not attached to the bony sternum; this flattening of the curve of the ribs and the approach of their free ends towards each other reduce the thoracic cavity, just as in our illustration of the boat its capacity would be reduced if we forcibly narrowed the distance between the thwarts. On the other hand, we see that by increasing the thoracic capacity, and so increasing the distance between the ends of these ribs, we are applying a mechanical principle which by a reverse action tends to straighten the spine” (Alexander, F.M.; Man’s Supreme Inheritance (Third Ed., 1946), p. 185)

A: Apparently, your confusion rests on a misunderstanding of the meaning of Alexander’s sentence you produced. You just need to represent the model that Alexander described in writing and reason from it.

First notice that Alexander says “forcibly narrowed the distance between the thwarts” and not “narrowed the thwarts” of the boat. When you read a sentence implying a visual representation, it is good practice to model the representation visually to make sure it fits with your immediate understanding. It is a basic question of inhibition.

The thwarts are struts in a boat that run at a right angle to its midline. Narrowing the distance between the lower thwarts in our analogy means therefore “narrowing the distance vertically” and not horizontally as you are implying. You have simply mis-interpreted the model Alexander provided. Here is a representation of a boat with the thwarts highligted.

The analogy of the boat represent the frontal view of the ribcage. Increasing the distance between the thwarts indicates a series of movements increasing the distance between the frontal ribs in the vertical axis.

A: What Alexander means by “increasing the distance between the ends of the lower ribs” is to expand the vertical distance between the front ends of these ribs. If you remember the length-tension relationhip governing muscle force production, you will understand that it is easier to extend that vertical distance when the lateral distance is reduced (“narrowing the struts themselves”) because the pull from the lower part of the serratus anterior will then be far stronger Upward from the interior borders of the scapulae. Now, if Alexander sees that the flattening of the curve is associated with the approach of their free ends toward each other in the reduction of the thoracic cavity, then it logically follow that we will not find the curve on this plane: on the frontal plane, the approach of the free ends of the ribs, the reduction of the distance between the thwarts, increase the curvature of the boat! Alexander is manipulating the image in his mind and he must look at the thorax from another angle to make his statement. Indeed, from the sagittal view of the torso, it is easy to make sense of the sentence “this flattening of the curve of the ribs and the approach of their free ends towards each other reduce the thoracic cavity” by thinking of the curve of the lower ribs as seen from the side (Alexander usual point of view when he was observing his pupil).

My position is strengthened by the fact that Alexander makes various comments on the harmful lateral widening of the lower ribs:

‘The striking feature in those who have practised customary breathing exercises is an undue lateral expansion of the lower ribs, when several or all of the above defects are present, ‘This excessive expansion gives an undue width to the lower part of the chest, and there are thousands of young girls who present quite a matronly appearance in consequence. ‘The breathing exercises imparted by teachers of singing are particularly effective in bringing about this undesirable and harmful condition. (Alexander, F.M., “*Man’s supreme inheritance*”, Chaterson Ltd 1910, reprinted 1946, p. 167)

A: End.

What this exchange is showing is that the student had conceived a representation of Alexander’s words without reasoning with the models[10] he was providing. In fact, the student did not reason and link Alexander’s exact words to the mechanical representation, he just “reasoned on the fly” and did not flexibly connect all the constraints given by Alexander. And I will demonstrate that he did not and could not simply see what Alexander was proposing because his own unreasoned pre-conception of the mechanism was cohercing what he could reason or not.

1) I think that the student was prevented to reason along the lines drawn by Alexander’s models. He accepted the common belief that the lower ribcage should be expanded laterally when breathing in. His model of expanding the capacity of the boat was directly opposed to that proposed to Alexander because it fitted with the easy pre-conception, and he was put out of communication with his reasoning because he had a strong feeling that expanding the lateral distance between the lower ribs was ‘right’ as it was what he was habitually doing and certainly what he had seen his own teachers do. He never checked that what was habitual use to him was opposite to what Alexander was hinting at not only in this passage, but in his other writings on breathing. The fact that Alexander model disagreed both with the academical explanation of the mechanism and his feeling impression had put him out of communication with his reasoning. Otherwise he would have reflected that the widening the thwarts laterally in the boat analogy would tend to shorten the boat along its axis of symetry and not the opposite.

It is clear that he did not challenge his representation of the mechanism with the other rules that Alexander is putting forward: if Alexander was really talking about a lateral widening of the free ends of the lower ribs, what could then be the incorrect “flattening of the curve of the ribs” he associates with the shortening of the distance? When one tries to re-construct the reasoning with a model, reasoning should not stop at the first constraint but continue to incorporate all characteristics which must match the description given by the author.

We start to read a book, but immediately we reach a point with which we disagree our more or less debauched kinaesthesia cannot control the impulses which, when set in motion, put us out of communication with our reasoning. (Alexander, F.M., “Constructive conscious control of the individual”, Integral Press 1923, reprinted 1955, p. 93)

2) Indeed, he did no link the first part of the explanation Alexander had given with the second part that comes just after it. He did not connect the fact that a lateral widening of the struts would, in the analogy proposed by Alexander, make the principle of straightening the spine by a reverse action of the ribs completely incoherent, incomprehensible and impenetrable.

On the other hand, we see that by increasing the thoracic capacity, and so increasing the distance between the ends of these ribs, we are applying a mechanical principle which by a reverse action tends to straighten the spine”

In the end, what Alexander is saying is utterly counterintuitive (as it is often the case), and it is only by using his models to construct experiments of conscious guidance which are bound to feel wrong, contrary to our most ingrained habit of expanding the thoracic capacity and breathing, that we can evaluate what he is proposing. His model is an invitation to conduct our inquiry further by making a procedure to experiment in practice and, thereby to construct our conception, not on beliefs, but on theories properly tested in order to “assign sufficient reasons for the forms he adopts“. This is what a personal process of inquiry is about.

This said, I have never seen a modern Alexander technique student who upon hearing this explanation would attempt to direct the different antagonistic movements which allow the increase of the distance between the free ends of these ribs: the students trained by the touch-technique do not experiment by themselves on a reasoned basis as they expect their teachers to “give them” the correct coordination with touch! This trusting attitude is fairly frivolous when one observes the coordination displayed by the supposed senior teachers and trendsetters in the modern Alexander technique community.

If they had reasoned with the model, they would have instantly linked this harmonic expansion of the torso with the two instructions Alexander used commonly in the first training course: “Upper torso comes forward” and “back back“.

For the coordination of the movements to be perfect, the *Throat* (name given to the top of the sternum) must be directed not only forward (this describes a movement of the first thoracic vertebra in space relatively to the frontal plane of the middle torso which form is dictated by the thoracolumbar adjustment) but also upward (this describes a movement of the first rib relatively to the first thoracic vertebra). Then the curve of the ends of the free ribs would be properly arched (yellow curve which links the ends of the green ribs).

When looking at the ribcage from the front we see that by increasing the distance between the free ends of these ribs, we are going to unflatten the curve linking the free ends of the ribs seen from the side in yellow color on the diagram above. This consideration of both planes (frontal and sagittal planes) of the thorax is the kind of manipulation called thought-experiment which helps to make flexible decisions in our experiments. On the frontal plane, the free ends of the ribs (represented without the costal cartilages) are like thwarts expanding away from one another and on the sagittal plane, they are like a curve more or less flattened depending on the distance between the thwarts.

The experiment of conscious guidance suggested here consists in finding and performing the concerted movements of the different parts of the torso which lead to the opposite of the “flattening of the curve of the ribs” and “narrowing the space between the thwarts” categorized by Alexander as “bad use” in the thwarts sentence. Alexander has also given, in his last book, a visual representation of the extreme flattening of the curve that is possible with the movements of the different parts of the torso and “a strong will”: the plumb line gesture.

On this image used by Alexander as a model of wrong use in standing (Alexander, F.M., “The universal constant in living, Chaterson L.t.d., 1942, third edition 1947), I have indicated the movements of the different parts of the torso (upper torso, lower back, sitting bones) which together flatten in yellow the curve at the free ends of the lower ribs.

The pupil must understand the given models, he must represent clearly the curve that is habitually flattened when the upper torso is pulled back and the back pulled forward in order to conceive the new movements which will be necessary to increase the curve. I do sometimes ask the pupil to place four fingers on the free ends of the lower ribs below the height rib to monitor how their concerted movements of the different parts of the torso can increase the curvature; I also ask him to register the increase in distance between the fingers which accrue when he is giving consent to the movements of the back back and the upper torso forward. Only then will he be able to realise that Alexander words are really describing a constraint of the mechanism and he will be able to use his reasoning to order the new concerted movements which will allow him to gain previously unknown experiences by reasoning from known to unknown experiences in the process of bringing about change in his manner of use.

This result does not come about by inducing self-hypnotism, or because of some chance happening, as, for instance, the coming into contact with an outside influence, personal or otherwise, or the possession of some natural aptitude (habitual reaction) which is fitted to produce a certain desired result. In all these cases instinct rather than the thinking and reasoning processes is relied upon, whereas “reasoning from the known to the unknown,” as in my technique, depends upon the conscious employment of means that conform to biological, physiological, and other laws known to us; in which, also, the observation of phenomena in cause and effect can be tested according to strict scientific method, so that, as Dr. Dewey writes in his Introduction, “the causes that are used to explain the consequences, or effects, can be concretely followed up to show that they actually produce these consequences and not others.” (Alexander, ccci, “Preface”, p. viii)

Expanding the torso is the primary gesture, not breathing

There is one consequence of this reasoning based on the model provided by Alexander which I want to highlight: this harmonic expansion of the torso is not a consequence of the movements commonly associated with breathing but that of the coordination of the movements of the parts of the torso, and as the (new) movements of breathing are (for Alexander) not even secondary to the conditions created by the expanding readjustment, they will have to adapt to the new conditions of harmonic expansion of the thorax (Alexander, F.M.; Why we breathe incorrectly”).[11] This means that the pupil will have to make the experiment of increasing the curve between the free ends of the lower ribs (expand the vertical distance between the thwarts) while narrowing the lateral distance (contract) between the free end of the lower ribs in exactly the same manner in both gestures of breathing-in and breathing-out. Succeeding here will automatically mean that he will have had to refuse to give consent to his habitual breathing movements (up and outward, down and inward) in order to maintain the model in this procedure. When he does contradict his feeling sense in this habitual gesture and to his immense surprise, he will measure (on a video recording) that the length of his breathing-out time has tremendously increased while he can take more air-in in breathing for less than a second. This conscious control of the time of out-breath and in-breath is in stark contrast with the strongest feeling of doing the wrong thing when performing the concerted orders. How could feeling so wrong lead to such an increase in the control of the breathing act?

Most modern Alexander teachers have forgotten that, at the end of his teaching carreer, Alexander commonly used the instruction “Allow the ribs to contract and expand“. Goddard Binkley reports[12] that in 1953 (just two years before F.M.’s death), he had lessons with Alexander in the Training Course, and that Alexander always emphasized this double instruction in his lessons with him. Yet Goddard Binkley does not seem to understand what Alexander asks him to direct, and he views the instructions as sequential (one after the other) and not as altogether, simultaneous (but on different planes). When I asked Walter Carrington about this (1997), he said he had “forgotten” about it and when I pressed him to give me his understanding regarding this definite instruction, he gave me the same answer as I had received before from all the senior teachers I had questioned: “Allow the ribs to contract and expand” refers to the idea of not interfering with the “natural movements of breathing“. I could not accept this Victorian idea —”you have not been breathing correctly yet, start breathing correctly now“— with the fact that these instructions were associated with “the old conception of breathing” or with so-called “natural movements” because it was in total contradiction with Alexander’s statements.

This preconception regarding natural breathing movements is that the outer chest capacity and particularly the lower chest capacity should vary largely to “power” the breathing movement, as if the lungs were not made of elastic material attach to the pull of the diaphragm. The supporter of this easy visualisation imagines that the lower ribs should go down in breathing out and up in breathing in. These movements are very marked only in the lower ribcage and they tend to restrict the expansion of the upper ribcage. I have even seen various times modern Alexander teachers place their hands on the side of the lower ribcage of their pupils and request them to feel and contract (down) and expand (up) their lower ribs to the full, in rythmic accompaniment of the breathing pattern!

Now, if you understand the models described by Alexander and you give consent to the series of three movements which allow the increase of the curve between the free ends of the ribs and simultaneously expand the vertical distance between the thwarts (seen from the front) while narrowing the lateral distance between the same free ends of the ribs, you will discover that in this case, the movements in and out of the lower ribs are fast disappearing totally with a fast increase on the control of the duration of both the in- and out-breath. On the contrary, if you want to force the habitual breathing movements to appear on the video recording, you will find that it is necessary to hollow the back, to protrude the abdomen and to pull the upper torso backward in space!

Remember now Alexander’s comment: The striking feature in those who have practised customary breathing exercises is an undue lateral expansion of the lower ribs, and you will have an idea of the faulty teaching which can only bring catastrophic consequences in the direction and control of the movements of the different parts of the torso as well as in the breathing process of the poor future teachers.

Here is an example of the result of the modern Alexander technique unreasoned teaching method. This teacher has been trained for three years and she is now conveying a supposedly correct sensory experience to her pupil.

The green markings on this image represent the relaxed serratus anterior with its nine ‘heads’ —the muscle working ‘conditions’ are not the result of the teacher relaxing it (she probably has no recognition that there is such a muscle or that it participates in the movements of the shoulder forward and the ribs back and up) but it is caused by the different movements she has given consent to to assume her lunge gesture. I have traced in yellow the flattening of the curve: as the lower ribs are much shorter than the ribs of the middle thorax, the vertebrae they are attached to need to be much more forward than the ones which are attached to the longest ribs of the middle torso to produce the effect of a flattened curve: the hollow in the back, the protruding abdomen, the narrowing of the free ends of the lower ribs, the reduced thoracic cavity and the pulled back upper torso are all symptoms of the same cause, the poor coordination of the different movements of the different parts of the torso. Apparently she is not conscious that she is giving consent to this series of movements.

“This flattening of the curve of the ribs and the approach of their free ends towards each other reduce the thoracic cavity“… (Photo taken from a internet website promoting the modern Alexander technique)

We can disarm the argument that breathing movements are directly associated with ribs movements in theory and now in practice. For Alexander, it is clear that “the primary movement” has never been “breathing”. The primary movement is the organisation of the movements of the different parts of the torso to increase its mean capactiy; therefore the primary movement in breathing is not the lateral movement of the lower ribs up and down which only increases the lateral width of the lower thorax (and tends invariably to narrow the upper thorax). It is a series of movements which lengthen and increase the mean thoracic capacity both in breathing-in as well as in breathing-out. You could call “full thoracic breathing” or “full chest breathing“, i.e., breathing with a full thoracic capacity where the lungs are, i.e., with minimal movement of the lower ribs outward.

To understand this sentence, it is fundamental to have a representation of the position of the lungs in the model we are using. On this x-ray in frontal view, the patient is examined in full inspiration[13] and it is clear that the lower ribs movements in the abdominal region have next to no bearing on the total lung capacity. The lungs are much higher than most people spontaneously believe, much higher than the free end of the lower ribs.

On this x-ray, the lungs are fully inflated and the red arrows I have added show that the lateral expansion of the lower ribcage is not related with full thoracic breathing.

When the upper thoracic cage is fully expanded in the full thoracic breathing during the breathing out and the breathing in, participating in the lengthening of the spine in both phases, the ‘real’ breathing movements will happen inside the thoracic bony cavity.

The instruction I use “Allow the ribs to contract laterally on the frontal plane and to expand vertically on the sagittal plane” is a reasoned instruction based on the two models given by Alexander. It is not an instruction specific to the tertiary part of the process, i.e., breathing, but a real instruction regarding the primary movements of the different parts of the torso which is valid whatever the phase of the breathing process. It is certainly not an instruction specific to breathing.

I have often witnessed a debate between modern Alexander teachers who compare their opinions on human functioning, on the question of the lengthening movement of the spine when breathing in. If this was correct, it would mean that the external (outer) breathing movements are a primary part of the process of establishing the conditions of the spine and torso —and that breathing out would be structurally associated with shortening the spine. This goes against principle as I will demonstrate.

When Alexander describes the torso, he is adamant that the general capacity of the upper thoracic cage should be maintained wider than the lower thoraco-abdominal part at all times. This statement makes no sense if you need to exclude the movements of breathing because you have a model of breathing out which implies a movement to narrow the outer ribcage in breathing out!

Let us, for a moment, think of the thoracic and abdominal cavities as one fairly stiff oblong rubber bag filled with different parts of a working machine which are interrelated and interdependent, and which are held in position by their attachment to the different parts of the inner surface of this bag. We will then suppose, for the sake of our illustration, that the circumference of the inner upper half of this bag is three inches more than that of the lower half. As long as this general capacity of the bag is maintained the working standard of efficiency of the machinery is indicated as the maximum.

Let us then, in our mind’s eye, decrease the capacity of the upper part of the bag and increase that of the lower half until the inner circumference of the latter is three inches more than the former. We can at once picture the effect on the whole of the vital organs therein contained, their general disorganization, the harmful irritation caused by undue compression, the interference with the natural movement of the blood, of the lymph, and of the fluids contained in the organs of digestion and elimination. In fact we find a condition of stagnation, fermentation, etc., causing the manufacture of poisons which more or less clog the mental and physical organism, and which constitutes a process of slow poisoning. (Alexander, F.M.; “Man’s supreme inheritance”, Chaterson Ltd 1910, reprinted 1946, p. 11)

Model-based reasoning is associated with thought experiments. In case you wonder what a ‘thought experiment’ can be, it is exactly what Alexander request his reader to construct when he says “Let us, in our mind’s eye, decrease the capacity of the upper part of the bag, increase that of the lower half… we can at once picture the effect of the whole…”.

« Decrease the capacity of the upper part of the bag and increase that of the lower half until the inner circumference of the latter is three inches more than the former »: is this not what people do when after having breathed out by pulling the ribs down («contract the ribs») they then let the air come in again by expanding the lower ribs («expand the ribs laterally»). In this habit, described as two different acts —contract the ribs, expand the ribs— the primary movement is breathing itself, and the lengthening and widening of the torso, the increase of the mean thoracic capacity is sacrificed to the common misconception and to the disregard for the proper lengthening and widening of the torso.

If the breathing out movement is a lowering of the sides of the lower ribs, we find by reasoning with a model including the thoracic diaphragm that at the end of the exhalation, the lateral length of the diaphragm will be at its shortest, the worse conditions for mechanical adavantage during the inspiration phase. This should force the subject to expand the lower ribs very fast to the side to allow for a short in-breath necessary for elocution or singing —it never works in practice, forcing the pupil to gasp or sniff loudly, increasing the speed of air and not letting the atmostpheric pressure do its role.

In order to contract optimally, the diaphragm must be lengthened and widened by the antagonistic movements of its bony attachments and not bowed down on its sides at the moment of breathing in. Therefore it is reasonable that the diaphragm length and width should be optimal before breathing in: its insertion at the lower back should be furthest away from the sternum (in a movement of the lower back back) and its origins, at the sternum (xiphoid process) and at the inferior thoracic aperture (along the costal margin) should be moved at their highest point without hollowing the back. This clearly indicates that Alexander’s conception of full thoracic breathing during both expiration and inspiration can be sustained in theory: all that is left from there is to be prepared to experiment —to feel uterly wrong in the process— and to consciously control the effect of this manner of use on the mastery of breathing out (whispered Ah) and breathing in (reversed whispered Ah). The pupil will have to test whether it is humanly possible to simultaneously “contract the ribs” laterally and “expand the ribs” vertically to obtain a widening of the thoracic cage, not at its lowest part, but at apical end (the top of the thoracic cavity).

This analyses of Alexander’s use of models could be expanded indefinitely by exploring all the descriptions he gives in his books, but it is sufficient for the moment to indicate how much reasoning with models can help with structuring decisions of movements which can make appear the “unknown” that Alexander was talking about in all his books.

Model based reasoning as a basis for building a personal system of inquiry

Models are very interesting to reason from the known to the unknown because they can help mis-represent reality. In order to change our conception of the movements of a complex mechanism, it is necessary 1) to misrepresent the naive ‘reality’ which we spontenaously consider as the reality of our movements because it is how we feel it should function and 2) to devise conscious guidance experiments to answer the questions suggested by the model.[14]

Model-based reasoning refers to using visuospatial models to reason, to practice thought-experiments[15], to open new areas of investigations, to form theories and to prepare controlled physical experiments. Models provide a visual-representation (either in 2D or 3D), they describe the relations between certain aspects of some mechanism in nature (but not others, example the x-ray), but they most of all allow us to construct appropriate vocabulary and terminology[16] to represent and test some mechanisms that seem obvious at a cursory glance but of which we understand next to nothing.

I have just shown in this article that the expression “expanding the thoracic capacity” (irrespective of the breathing movements) which Alexander considered integral to his one central idea of reeducation and readjustment, can only be reasoned with a definite model of the mechanism of the torso, otherwise the words have little definite meaning and just prepresent an expression of our preconception and as such, will forever stay ineffectual at changing our conception of the use of the mechanism.

These two actions—the re-education of the “Kinaesthetic Systems” and the increasing of the thoracic capacity which applies a mechanical power by means of the muscles and ribs to the straightening of the spine—are both aspects of the one central idea, and are not separate and divisible acts. (Alexander, F.M., “Man’s supreme inheritance”, Chaterson Ltd 1910, reprinted 1946, p. 180)

During the last 15 years, educational theory researchers have connected the great paradigm shifts in science —the radical conceptual changes— to the activity of model-based reasoning that the scientists employ when inventing new ways to understand what is happening in the world. Their theory is now directly linked to science pedagogy as they found that, instead of teaching science by solely asking the students to learn “the solutions of science” by rote, it could be fruitful to make the student learn to reason with the tools of the creators of science, i.e., to reason with strict models and strict word meanings.

I am just following this same trend with the teaching of the Alexander technique as

1) I see a great similarity between A- Alexander’s radical change of conception which led to the creation of his initial technique of conscious guidance and control (anti-somatic technique) and B- the radical conceptual changes that the scientific inventors proposed to understand the world around us,

The direction of coordinated movements of the different parts of the organism by reasoning instead of by feeling is the greatest shift in the history of gestural guidance and control.

Faced with this, I now saw that if I was ever to succeed in making the changes in use I desired, I must subject the processes directing my use to a new experience—the experience, that is, of being dominated by reasoning instead of by feeling, particularly at the critical moment when the giving of directions merged into “doing” for the gaining of the end I had decided upon. This meant that I must be prepared to carry on with any procedure I had reasoned out as best for my purpose, even though that procedure might feel wrong. In other words, my trust in my reasoning processes to bring me safely to my “end” must be a genuine trust, not a half-trust needing the assurance of feeling right as well. (Alexander, F.M.; The Use of the Self, Its Conscious Direction in Relation to Diagnosis-, (Third Ed. Centerline Press 1946), p. 22)

Learning the initial Alexander technique represents a leap forward and away from all the attempts at somatic education, yet, to subject the processes directing our use to the new experiment —the experiment of having the concerted movements of the parts of the torso dominated by reasoning instead of by feeling— the first need is to help our student reason correctly and flexibly with appropriate models.

2) there is no greater goal for a teacher than to help his pupils form their own system of inquiry into the guidance and construction of coordinated movements of all the parts of the mechanism of the torso. Contrary to the doctrine of the modern Alexander technique, I do not think that the teacher’s task is to make the pupil experience “what is right”, i.e., to feel the correct coordination time and again, until the association between the experience and some verbal orders becomes a “good habit”. There is a much greater —and more fruitful— task for the teacher, that is to help the pupil free his thinking from the immediate feelings (what I call the freedom from the tyranny of the feeling sense) and develop his capacity to construct a strong relation between his speech and dynamic models in order to form his own system of inquiry, his own system with which to challenge his pre-conception and fixed ideas regarding what is possible or not for him.

Model-based reasoning cannot develop without a proper re-education

As much as model-based reasoning plays a central role in the construction of higher conceptualization processes and in the dismantling of pre-conception and naive embodied theories about how mechanisms functions, it has also been shown that reasoning with visual models —spatial representations in the form of diagrams, graphs or physical models— is not innate, that students have great difficulty to represent dynamic models when left to their own means and even more difficulties to reason accurately from a model.[17]

The students have not been trained to construct and employ models in order to understand complex mechanisms. Even when models are given, students (and teachers) will avoid reasoning with them so that they tend not to understand what “working to principle” in constructing controlled experiments could mean. This explains why models are often critisized as being less than “the reality” as well as fixed images which lead to fixed and wrong conceptions. The two criticisms are often correct together (which should be impossible) because students believe that the models which are presented are concrete representation in visual form of the mechanism they describe; the somatic teacher will in his turn use this imaginary fixity as an excuse not to reason and to reject anything which does not correspond to the doctrine he has swallowed whole (without reflective thinking) in his training.

The initial Alexander technique lessons represent for them a great opportunity to develop “principled understanding” and “principled practice” which need to be developped and taught to “understand” the Alexander technique. You cannot reconcile people with the idea of reasoning if you do not train them to employ definite terminology and to manipulate models in their mind to find solutions to precise questions. This is the main surprise for the students of the initial Alexander technique: how many times during their lessons they are asked to reason in order to answer questions relating to a given model. Many could imagine that this is a coincidence or a secondary trait of these lessons. It cannot be further from the truth. This form of conversation is how they will get into the habit of inquiry, of using models, questions and logical structures in order to produce decisions and to understand why these decisions must be maintained in time during the procedures of conscious guidance.

The process of inquiry is one of developing and testing theories to explain phenomena. The difficulty lies not in the lack of theories, but on the contrary in their proliferation and in the lack of conscious control of the explanations teachers and students give of most phenomena. When the specialist of science education Richard A. Duschl thinks that people are natural theory builders,[18] I consider it would be more accurate to say that they are compulsive theory builders. Without any system of inquiry, without any system to control the relevance of their theories (“In the evaluating process, a major criterion for success is the goodness of fit of the theory to the phenomena”), they will “have” a conception about almost anything and their internal speech will be saturated by the accumulations of these somatic theories to the point of leaving very little place for learning something.

Nor must it be forgotten that in this process of reeducation a great object lesson is given to the controlling mind. In the very breaking up of maleficent co-ordinations or vicious circles which have become established, a new impulse is given to certain intellectual functions which have been thrown out of play. The reflex action which is setting up morbid conditions can only be controlled and altered by a deliberate realization of the guiding process which is to be substituted, and these new impulses to the conscious mind have, analogically, very much the same effect as is produced on the body by the internal massage referred to above. The old accumulations of subconscious thought are dispersed, and room is made for new conceptions and realizations. (Alexander, F.M., “*Man’s supreme inheritance*”, Chaterson Ltd 1910, reprinted 1946, p. 173)

Of course there is a price to pay for this mass production of theories: more than 80% of these theories are incoherent (they aggregate parts of theories that are irreconcilable with each other), or they are incomplete, and the rest are misguided (the terminology used in them is incoherent and misleading —most of the times, the main arguments have no unique definition so that it is not possible to apply basic principles of reasoning like the non-contradiction principle).[19]

The overabundance of untested theories in the mind of the pupil has two very serious drawbacks: 1) it encourages a form of subjective callousness and indifference to a proper evaluation of theories and 2) it does not insure a secure platform from which executing solid decisions.

false theory protectionism

Compulsive theory builders invest their theories with a lot of personal affect. They are not used to challenge the theories they support, as if questioning a theory they believe in would be a personal attack on their own self. This attitude does not take into account that, most of the time, naive theories are potpourri —rotten pot— of new Age and old Age misconceptions which paternity is very difficult to trace. The fact that there is very little “personal” in them seems to be inversely proportional to the tendency of the compulsive theorist to attach a lot of his personal worth to what he considers “his” theories. This explains why a weak theoricist would tend to reject with the utmost force anything or anybody who is seen as representing a theoretical threat. This does not exclude a penchant to promote a relativist, all-is-good attitude regarding conceptions —why should another conception be better than mine or not coexist with mine? — because this penchant goes well with the anathema (strongest denunciation) of theory analysis and criticism.

weakness to maintain solid decisions

To execute solid decisions, i.e., to maintain in practice the decisions to do movement (a) when doing movement (b) and movement (d) together, the words contained in the instructions must be clearly and uniquely defined, i.e., they must be defined relatively to a same model of the mechanism. Alexander explains that the pupil must have formed a complete and accurate apprehension of all the movements concerned: this can only mean that he must have constructed a model which represents a mechanism relating the three movements together —what is at the beginning physically impossible for him to perform as these concerted movements are contrary to his habit of use (his habit of concerted movements).

We must therefore make him understand that so very frequently in re-education the correct way to perform an act feels the impossible way. There is only one way out of the difficulty. He must recognize that guidance by his old sensory appreciation (feeling) is dangerously faulty, and he must be taught to regain his lost power of inhibition and to develop conscious guidance. (Alexander, F.M.; Man’s Supreme Inheritance (Third Ed., 1946), p. 155)

In activity, the pupil must have constructed a model with which movement (a), (b) and (d) can be kept in working memory with the clear description of the relations between movement (a), (b) and (d), for it is only in knowing in advance how movement (a) can interfere with movement (b) and (d) that movement (a), (b) and (d) can be given consent to occur simultaneously and produce a totally unknown (feeling) experience.

My next effort must be to give X a correct and conscious guidance and control of all the parts concerned, and in order to obtain this control, he must have a complete and accurate apprehension of all the movements concerned. And this apprehension must precede and be preparatory to any conception of “speaking,” [the doing for which the means-whereby orders are indispensable] during the application of all the guiding orders involved*. (Alexander, F.M., “Man’s supreme inheritance”, Chaterson Ltd 1910, reprinted 1946, p. 32)

This is the conclusion, for now, of this article about the connexions between the words ‘reflexion’ standing for reasoning and ‘reflection’ standing for visual model as seen on a mirror.

[1] In the chapter we are talking about, but in its conclusion, I used “reflection” in the sense of

[2] “In all these efforts to apprehend and control mental habits, the first and only real difficulty is to overcome the preliminary inertia of mind in order to combat the subjective habit”. (Alexander, F.M.; Man’s Supreme Inheritance (First Ed., Paul R. Reynolds, 1910), p. 95)

[3] Carrington, W.; Two private lessons with Walter Carrington, 1997, 8min37sec —Masoero, J.; Transcription from the DVD.

[4] The definition of mechanism is a very interesting one: the systems of parts and processes in an organism that work together to perform a particular function by combinations of the physical movements of its parts.

[5] “The issue is not theory-using, but theory-finding; my concern is not with the testing of hypotheses, but with their discovery. Let us examine not how observation, facts and data are built up into general systems of physical explanation, but how these systems are built into our observations, and our appreciation of facts and data. Only this will make intelligible the disagreements about the interpretation of terms and symbols within quantum theory”.

(Hanson, N.R.; Patterns of discovery, Cambridge University Press, 1965, p. 3)

[6] “Those who have read the account of the evolution of my technique in The Use of the Self will be aware that I was continually led into unknown experiences, and when employing new “means-whereby” found myself in unfamiliar situations, and experiencing impeding and illuminating adventures in dark places. This was appreciated by the late Joseph Rowntree when he said of my technique that it was “reasoning from the known to the unknown, the known being the wrong and the unknown being the right.”

This experience of passing from a “known” to an “unknown” manner of use of the self is the basic need in making a fundamental change in the control of man’s reaction, and he will remain impotent in meeting it, unless it is possible to give him the opportunity of accepting an unfamiliar theory and of acquiring the experience of employing consistently the unfamiliar procedures which are its practical counterpart, by meanof an integrating process of reconditioning associated with experiences of use and functioning previously unknown to him. (Alexander, F.M.; The Universal Constant in Living, (Third Ed. 1946, p. 172)

[7] “The truth of the matter is that in the old morbid conditions which have brought about the curvature the muscles intended by Nature for the correct working of the parts concerned had been put out of action, and the whole purpose of the re-educatory method I advocate is to bring back these muscles into play, not by physical exercises, but by the employment of a position of mechanical advantage and the repetition of the correct inhibiting and guiding mental orders by the pupil”. (Alexander, F.M., “*Man’s supreme inheritance*”, Chaterson Ltd 1910, reprinted 1946, p. 181)

[8] Alexander did not ‘invent’ this procedure. It was practiced by Delsarte who had seen the masters of Bel Canto teaching it under the name of “lota vocale”.

[9] A muscle working at a longer length provides more pulling force and elastic resistance for less activation. It is one aspect of the mechanical advantage we are looking for.

[10] I say two models because it is not possible to make sense of Alexander cause and effect reasoning without using the obvious frontal plane and the secondary sagittal plane.

[11] “Let me make myself clear by explaining that the man who breathes incorrectly and inadequately, does so as an immediate and inevitable consequence of abnormal and harmful conditions of certain parts of his body. The man who breathes correctly and adequately does so as an immediate and inevitable consequence of normal and salubrious conditions of the same parts. It therefore follows that if the conditions present in the second man can be induced in the first, he will then, but not otherwise, be a correct and adequate breather. And the process by which this is achieved is simply a readjustment of the parts of the body by a new and correct use of the muscular mechanisms through the directive agent of the sphere of consciousness. This change brings about a proper mechanical advantage of all the parts concerned, and causes, thanks to the right employment of the relative machinery, such expansion and contraction of the thoracic cavity as to give atmospheric pressure its opportunity.

Now here we have (a) the directive agent of the sphere of consciousness, and (b) the use of the muscular mechanisms-— the combination causing certain expansions and contractions, and the result being what is known as breathing. It will at once be seen, therefore, that the act of breathing is not a primary, or even a secondary, part of the process, which is really re-education of the kinaesthetic systems associated with correct bodily postures and respiration, and will be referred to universally as such in the near future. As a matter of fact, given the perfect co-ordination of parts as required by my system, breathing is a subordinate operation which will perform itself.

Alexander, F.M., «*Why we breathe incorrectly*», 1909. cited in *Man’s supreme inheritance*, pp. 88-89

[12] Binkley, Goddard; the Expanding Self, how the Alexander technique changed my life, STAT-books, 1993, pp. 116, 118, 129.

[13] All thoracic x-rays are done in full-inspiration, holding the breath, otherwise the contrast on the lungs is insuficcient.

[14] “Progress is made by devising experiments to answer questions suggested by the model” (Hesse, 1953, p. 199) (Nersessian, N.J., Magnani, L., Thagard, P.; Model-Based Reasoning in Scientific Discovery-Springer US (1999), p. 30).

[15] Thought-experiments are nothing other than speech-experiments in which can be tested our theories and conceptions of how things work in practice.