To See or not to See, reflexion on pedagogical tools

The problem is of changing coordination by creating a new concerted activity, not of refining sensory appreciation

If the problem is somatic in origin, therefore it cannot be changed by somatic means.

And to those who are advocating individual right and individual endeavour in the world to-day, I venture to suggest that as a training for the realization of these commendable ideals, no more fundamental experience is available than that which comes to the person who, with or without a teacher, will patiently devote the time to learning to apply the technique in the act of living. The desire that mankind will come into the heritage of full individual freedom within and without the self still remains an “idealistic theory.” Its translation into practice will call for individual freedom IN thought and action through the development of conscious guidance and control of the self. Then and then only will the individual be liberated from the domination of instinctive habit and the slavery of the associated automatic manner of reaction.

(Alexander, F.M.; The Use of the Self, Its Conscious Direction in Relation to Diagnosis, (Third Ed. Centerline Press 1946).pdf, p. x).

When I read this quote, I wonder which technique Alexander is talking about. The choice discussed in this post is between asking a pupil to apply a reasoned technique OR a somatic technique in the act of living.

For my part, I believe in the individual right of any human subject to understand how he can improve his own coordination by his own means. I am not talking about acquiring a somatic knowledge, a ‘first-person experience’ of what feels right at a certain moment in time, in peculiar circumstances, some feelings that is as fleeting as it is indescribable, but about real conscious reasoned capacity to think with explicit principles and rules set in valid verbal language which can help the pupil develop his power of initiative and his capacity to make intelligent experiments and formulate decisions regarding the changes in use of the self demanded by the ever changing environment.

Conscious, reasoned psycho-physical activity must replace subconscious, unreasoned activity in the processes concerned with making the changes demanded by the ever-changing environment of civilization (Alexander, F.M.; Constructive Conscious Control of the Individual (Eighth edition, 1946), p. 31).

I also believe that without a gradual improvement of his reasoning processes and consequent renewed understanding on the part of the individual, there can be no fundamental change in the coordination with which the pupil will respond to unfamiliar situations. The pupil is accustomed to react to what he feels, and therefore, to develop freedom in thought and action, he needs to be given proper tools to think intelligently, to bring into mind some things that are not present in his feeling sense, to step outside of his present feeling, to move beyond the situation as it is presented to his senses, and to conceive alternatives.[1] The development of conscious guidance and control rests on giving the pupil tools of the mind that he does not already possess and on training him to use these tools to think and reason from and beyond his present feeling situation. This is the raison d’être of the initial Alexander technique.

This forces me to disagree completely with G. Trevelyan who wrote shortly after qualifying as a modernAT teacher that “the joy of the work, however, is that the pupil can be given a good habit whether he likes it or not, because we are working on the sensory side and not his mental.”[2] It is easy to demonstrate that this is an unacceptable interpretation of the initialAT, i.e., the technique Alexander employed to change his own general use.

My main point of disagreement is not, however, on his representation of the authoritarian aspect of the transaction between the modernAT teacher and his pupil in its different nuances (I have also heard:“the pupil can be given a good habit of use whether he wants it or not”), but on the very center of the clause suggesting that the pupil can be given a good habit of general use by having someone else, an external authority, “work on his sensory side” as if this kind of intervention could “perform a miracle” and make the pupil come into possession of intelligence[3] because he feels more, better or differently.

First of all, it is necessary to stop and consider how the modernAT teacher intents to “give a good habit of use” to the pupil whether he wants it or not. In the words of Lawrence Smith, this imposition is achieved through a “correction and refinement of sensory awareness” of the pupil by the teacher using touch. Lawrence Smith is a senior modernAT teacher who reacted publicly to one of my interviews on YouTube in which I explained that the self-teaching process advocated by Alexander is not about constructing a ‘feeling direction’ but a ‘reasoned direction’ of the concerted movements of the different parts of the torso.

In case you have not seen his comment relayed on FaceBook, here is an excerpt of what he wrote:

Lawrence Smith: I think that my 40 years in the Alexander Technique have been very much about correction and refinement of sensory awareness. Isn’t learning to notice the sensory signals that occur when you fix, compress, and retract what is taught in private lessons, with its hands-on guidance and immediate feedback?

In fact, what led me to the A.T. was a mechanical approach to body positioning. As a dancer and performer, I looked pretty good on film, in spite of the excessive postural tone that made my posture look “right”. This excessive tone from right positioning led to multiple injuries.

I think the mechanical approach advocated here has obvious limits. It you don’t correct faulty kinesthesia, will you always rely on mirrors, cameras, and observers to correct misuse? This certainly is not what I learned in my A.T. training and Tai-Chi study.

I agree totally with Lawrence Smith that the lesson of modernAT is exactly about directing the attention of the pupil toward discrete sensory signals that occur here or there when he is moved in one way or another by the teacher’s manipulations. The pupil’s mind is not directed toward seeing, acknowledging and intentionally modifying a concerted activity, objective movements he is doing with the different parts of his torso. The pupil is not asked to study the psychophysical problem consisting of directing a series of movements altogether[4], but to witness some feelings of tension or release without any relation to his whole reaction to an activity. Through hands-on, the pupil is only getting a fragmented view of his activity, and this somatic mosaic has nothing to do with the principle of the construction of an ‘unity in activity’, the unity of thought and action. Thinking an order is one think, but the real task, i.e., to obey that order in activity, begins when we start to put into practice our decisions.

The task of reasoning out and selecting the effective means of bringing about psycho-physical change according to this new principle is not an easy one, but the real task begins when we start to put into practice the procedures which we have decided upon, for this, as Dewey puts it, presupposes a “revolution in thought and action”. (Alexander, F.M., “*The universal constant in living*, Chaterson L.t.d., 1942, third edition 1947, p. 26)

I also agree particularly on the immediacy of the feedback provided by the touch-teacher, pointing to the fact that the pupil is not reasoning and linking the instructions of release he is asked to give (or not) with a series of connected movements of the different parts of the mechanism he intents to guide. The pupil is not instructed to think in terms of an interaction of different movements of the parts of the torso with the rest of the organism, but in terms of symptoms, feelings of tension, feeling of fixation, feelings of compression and sensations of stiffness.

My objection is that ‘immediate’ means that there is no mediation by the reasoning process, that the pupil is just learning to recognize disjointed feelings and to associate them with a simple label —‘bad’ or ‘good’—. Where is the call to the reasoning processes to unite a series of means-whereby movements in this? Where is the revolution in thinking and action which Dewey called “thinking in activity”?

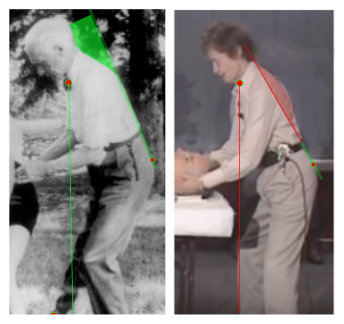

The pedagogical tool for diagnosis

When Lawrence Smith was evaluating that “he looked pretty good on film in spite of the excessive postural tone that made his posture look right”, it is obvious that he was not trained to see and analyze the conditions of use present, i.e., that he was not looking at nor reasoning about the concerted movements which dictated his postures. In my experience, an experience that is shared by all the teachers who have had lessons with me, if there is a symptom of an excessive postural tone or any other defect in the guidance of movements, they appear immediately in the fixity of the concerted movements by which the subject assumes his posture. The fact that it escaped Lawrence Smith’s observation is telling a great deal about his incapacity to consider the organism as a working unity in which the working of any part is affected by the working of all the other parts[5].

It is easy to mislead people into believing that an excessive postural tone could suffice to construct a correct gesture on a picture, but what this kind of disinformation really shows is the lack of understanding of Alexander’s process of evaluation of the conditions of general use in relation to faulty conceptions of movements.

The eye of an artist is needed to apprehend the faults in a painting or in a work of sculpture, and, above all, the defects in a human body.

To the aptitudes and intuitions of an artist, however, something more must be added before it is possible to become an efficient teacher of my principles. It is necessary to have special training in dealing with men and women and to possess that keen eye for character needed to detect and to eradicate the mental difficulties, and the vocal, respiratory and other physiological delusions which almost invariably accompany physical defects” [FMA, “A Protest against certain Assumptions…” 1910].

The art of seeing synchronized movements and to detect in unwanted movements the delusional physiological conceptions they reveal has totally disappeared from the touch technique to the point that many modernAT teacher publicly belabor the point that SEEING is not relevant to the Alexander technique. Each time I read their criticism, or the high opinion they have of their training which entitles them to judge all other teachers as unworthy, Alexander’s comment on the impossibility to become an efficient teacher of his principles without seeing and reasoning comes to my mind.

But for me, the problem has never been to judge who is or is not an efficient teacher of Alexander’s principles. What I scritinize in my quality of isolated teacher is the pedagogy because my job is to transmit the tools for each of my pupil to start teaching themselves when and how to apply the Alexander technique of conscious guidance and control. It stands to reason that the first tool I want to transmit to my pupils is a tool of diagnosis.

The question is not just to look at a picture and see. Alexander explains that he had to train himself in order to see the series of movements he was doing and which shortened his stature, protruded his abdomen, and curved his back. But it is astonishing what a pupil can decide when he reaches the point of being able to see, i.e., to go past the fixed image and think about the movements of the different parts of the organism which have caused the visible result.

“There is so much to be seen when one reaches the point of being able to see, and the experience makes the meat it feeds on”. (Alexander, F.M.; in Fisher, J.M.O, Articles and Lectures, 1995, Teaching Aphorisms, p. 205)

In the modernAT, the power of touch has totally swallowed Alexander’s principles and no special training is given to the pupil to reach the point of being able to see how concerted movements of the different parts of the torso dictate the shape of the torso. This is tragic-comical when seeing how definite movements are synchronized can give a valuable and explicit clue so that the pupil could form a general view, i.e., a reasoned view of his conditions of use as a whole instead of a collection of non-connected lists of feelings. When the pupil is guided to see and reaches the point of being able to see his concerted movements, it is true that the experience makes the meat it feeds on because the pupil is then in a position of understanding what he is working with (with or without the teacher) and how to affect with his decisions the “use of the self as a whole”.

The definition of the noun “use” is “the ability to move something with more or less dexterity, especially a body part“. But when Alexander employ the word “use”, it is not in that limited sense of moving one specific part, for he recognises that the movement of any part involves by necessity bringing into action the movements of all the other parts of the torso. For him, the conscious controlling of the movement of a particular part is of little practical value in the science of living. He calls it “the specific control” and explains for example that “the specific control of the neck should primarily be the result of the conscious guidance and control of the mechanism of the torso, particularly of the antagonistic muscular actions which bring about those correct and greater co-ordinations intended to control the movements of the limbs, neck, respiratory mechanism, and the general activity of the internal organs (Alexander, F.M.; Man’s Supreme Inheritance (Third Ed., 1946), p. 147).

I find it fundamental that my pupil understands both in theory and practice this principle of guidance of concerted movements, and this is why I teach him/her to see how the direction of the movements of the different parts of the mechanism of the torso determine the conditions of the movements of the neck, limbs, respiratory mechanism, etc. If I want a pupil to change his/her manner of use, he/she must be given to practice with a reliable tool of self-diagnosis. Without this tool, the pupil will forever be deceived by sensory appreciation.

“We shall also see how important it is that every one of us should know how to estimate the degree in which our functioning is being influenced in one direction or the other by our manner of use, so that we can with confidence check any trend of this influence in the wrong direction. In short, it will be seen that the ability to assess the influence of manner of use upon general functioning provides a basis that is fundamental for diagnosis.

The acceptance of this basis for diagnosis means a changed outlook for all who are seeking to help themselves out of their difficulties, or to make some change of thought and action” (Alexander, F.M.; The Universal Constant in Living, (Third Ed. 1946), p. 6).

What the pupil who is seeking to help himself out of his difficulty feels or has felt during hands-on does not provide a basis that is fundamental for diagnosis. Self feeling is untrustworthy.

The avowed disregard of modernAT teachers for visual observation of movements is in stark contrast with all the details which abound in Alexander’s books about observing movements and deciphering important clues for the reasoning processes and for establishing reasoned evaluations in view of making decisions which matter.

If you care to experiment on a friend in this act of rising, you will observe that in the movement as performed by an imperfectly co-ordinated person the same bad movements occur, tending to stiffen the neck, to arch the spine unduly, to shorten the body [the torso], and to protrude the abdominal wall (Alexander, F.M.; Man’s Supreme Inheritance (Third Ed., 1946), p. 171).

It is clear that Mister Smith has not conducted experiments of conscious guidance to observe how a series of movements occured, how the different parts of his torso would have interacted if he had commanded an unusual coordination in a routine activity. Then, he could have made a valid diagnosis of his subconscious coordination instead of saying that “it looked pretty good”.

Lawrence Smith views my work with disdain as a “mechanical approach” because he has no clue about the process of directing and projecting series of concerted movements to his reflection. Because he thinks in feelings, and refuse concerted movements evaluation as a basis for diagnosis, he cannot reason in term of ‘a conscious direction of a concerted activity’[6]. This explains why he sees ‘postures’ or ‘body positioning’ when I explain “concerted movements”.

I remember how, as a young trainee, I wanted the dream of the imposition of a correct habit of use by the hands-on of the modernAT teacher to be true. Yet, as a matter of fact, my wish did not come true and instead, I found to my surprise that Alexander had anticipated the debacle and even provided all the conceptual ammunition necessary to ruin his touch pedagogy in theory, as if he had left clues for his students to think and find ways NOT to imitate his way of teaching.

Strange as it may seem, I have always found that a pupil who uses himself wrongly will continue to do so in all his activities, even after the wrong use has been pointed out to him and he has learned by experience that persistence in this wrong use is the cause of his failure.

(Alexander, F.M.; The Use of the Self, Its Conscious Direction in Relation to Diagnosis, (Third Ed. Centerline Press 1946).pdf, p. 34).

When you ignore the concept of conscious guidance and control of the manner of use as a concerted activity, you would expect that making the pupil feel under your hands what is “a faulty kinesthesia” and learning from this sensory experience what he should do with release to obtain the “correct specific kinesthesia”, i.e., somatic reeducation, that it should help the pupil stop using himself wrongly in his activities. Strange as it may seem, it never happens. With hands-on it takes years and several hundred lessons to just scratch the surface of bad habits of mind and body. Mind you, if pupils were acquiring a “good habit of use” through their mAT lessons, “whether they wanted it or not“, don’t you think that modernAT would be acclaimed as the new panacea, a remedy for all bad habits and difficulties?Is it not because the Alexander technique has become a feeling good somatic technique that it is indistinguishable from other bodywork techniques?

If you think about it for a second, you will realize that what you feel is not the cause of your present coordination, but the result of it. The guided sensory experience to obtain a specific feeling is not targeting the real cause of the mis-coordination, it does not make the principle of unity work for good. Hands-on does not say anything about how you guide a series of concerted movements of the anatomical structure to assume a posture by yourself.

The manner of use, i.e., the series of movements you have often repeated will feel easy to repeat, and conversely, the coordination of movements you have never practiced will have the appearance of requesting tremendous mental and physical effort to obtain very little comfortable result. You would feel totally differently if you had trained yourself to repeat a different drill. Now ear this sad truth: nothing indicates that what feels easy and right after training is “right,” it just means that the ‘new use’ has become habitual and that your sensory appreciation has adjusted to it; on the other hand, to know whether your training is improving your manner of reaction or not, it stands to reason that you need something else, another criterion that your somatic feeling sense to ascertain that you are really changing your coordination.

It is telling that in mister Smith’s comments, he focuses exclusively on “excessive contraction,” suggesting once more that the discovery of “guided somatic release” has been his path to the solution of his problems. This is typical of most of his comments and reflects the view of many modernAT teachers: “It is absolutely essential to guide students out of habitual isometric contractions. Students need the example and the authority of contact [touch]”.

Now it is interesting to note that the way in which he analyzes the conditions of use present —pointing to the excessive habitual isometric contractions— does not correspond to the much more inclusive reasoning Alexander has explicited after watching his movements in his mirrors for month on end. Alexander says explicitly that if the pupil proceeds in the ordinary way to eradicate the symptom, here the stiffening, by doing a direct action, i.e., release guided by his feelings, he shall invariably fail. What is very interesting is his explanation for that failure:

For instance, if we decide that a defect must be got rid of or a mode of action changed, and if we proceed in the ordinary way to eradicate it by any direct means, we shall fail invariably, and with reason. For when defects in the poise of the body, in the use of the muscular mechanisms, and in the equilibrium are present in the human being, the condition thus evidenced is the result of an undue rigidity of parts of the muscular mechanisms associated with undue flaccidity of others. (Alexander, F.M., “Man’s supreme inheritance”, Chaterson Ltd 1910, reprinted 1946, p. 57)

If the pupil follows Mister Smith’s technique, he will try to feel for excessive tension and do what he can to release according to his feeling sense, without any regard for the whole picture which Alexander sees in his mirrors as the combination of an undue rigidity & an undue flaccidity of certain links between the parts. Despite the conforting feeling the pupil will experience, the end-gaining intervention of ‘release’ will just worsen the conditions of use, i.e., the matter of the whole coordination, as ‘release’ cannot bring about a due tension of the parts of the muscular system intended by nature to be constantly more or less tensed[7].

To claim the ‘authority’ given by touch is not the same thing as having a correct analysis of the conditions present. If excessive contraction is associated with undue flaccidity of other parts —I do not see how a touch-teacher could fault Alexander on this rule—, it is not the state of tension which must be targeted, but the concerted movements which cause both undue rigidity and undue flaccidity in all the elastic tissues which, most of the time, are not even felt as tense or lax. Certainly because they do not leave much trace in our feeling sense, their importance for the motor act is just disregarded. Proceeding in the ordinary way, trying to reduce the symptom of undue rigidity by release shall fail invariably, according to Alexander himself, as it is nothing else than end-gaining, i.e., a partial doing guided by feeling without any consideration for the whole interactivity between movements and conditions of functioning of the muscular system.

Some parts of the muscular system have been put out of action by lack of lengthening stretch —the fascias, ligaments and tendons are not delivering their share of the work of equilibrium in the form of elastic resistance because they have been put out of action by the manner of coordinating the different movements of all the parts of the torso— and the whole purpose of the initialAT is to bring back these elastic tissues into play by the conscious coordination of movements which creates a geometry of mechanical advantage in which the weight of each different part will act as a load to the geometric spring system, maintaining length and elasticity without any voluntary effort.

The truth of the matter is that in the old morbid conditions which have brought about the curvature [of scoliosis] the muscles intended by Nature for the correct working of the parts concerned had been put out of action, and the whole purpose of the re-educatory method I advocate is to bring back these muscles into play, not by physical exercises, but by the employment of a position of mechanical advantage and the repetition of the correct inhibiting and guiding mental orders by the pupil (Alexander, F.M., “Man’s supreme inheritance”, Chaterson Ltd 1910, reprinted 1946, p. 181).

It is clear that Alexander does not use a physiological definition of the terms “muscles” or “muscle system.” The “parts of the muscular system intended by nature to be constantly more or less tensed” are not “muscles” but mainly the strong, fiber reinforeced elastic tissues which surrounds muscles and link them to bones. These fascias can only produce forces when the bones they are attached to are moving apart and applying to the tissues a mechanical strain. This is the reason why we plan series of movements to lengthen the stature (of the torso) as a whole. Integrating all the elastic forces of the web of fascias has nothing to do with specific somatic releases. And it is only when the elastic structure is brought into play that real ‘relaxation’ can appear and that the muscle shortening contractions and isometric contractions used to fix and give an impression of stability can be effectively reduced in the process.

The whole purpose of the re-educatory method I advocate is to bring back into play the tissues which unwanted concerted movements of the rigid parts of the anatomical structure have put out of action. It stands to reason that new concerted movements should be the means whereby of a new use of the self as a whole. I am talking about movements concerted intentionally, not fixity, tension or release.

Mister Smith could only imagine “excessive isometric contractions” in his conception of “mechanical approach to body positioning.” What isometric contraction means is a contraction with an absence of movement (the joint angle and the length of the tissues do not change during the contraction). This is an eloquent slip in itself. The “mechanical approach” he wants to express his strong disapproval about was presented as a technique of conscious direction to command concerted movements! It is understandable that he would project his conceptions onto the work of others when he does not even understand the beginning of it.

The battle of reasoning from visual clues against the ‘example and authority of touch’

What objection can be raised against the ‘example and authority of touch’ which Mister Smith considers essential? Once again I do not want to talk about the idea of subordinating the pupil’s will to the authority of someone else: I leave you to consider the problem if you so choose. The main objection that I see is not moral but strictly pedagogical. The modernAT teacher is not proposing a correct model of reasoning and he is not offering at any point to make the pupil reason about concerted activity. Thinking about feelings and tension has nothing in common with the use or exercise the mind or one’s power of reason in order to make inferences, decisions, or arrive at a solution or judgments. On the contrary, it is well known that the authority of touch has the power to stifle all critical reasoning. Yet, this is the question which we must ask ourselves: is it not employing and relying on the reasoning process that led Alexander in the right direction? Alexander was never on the receiving end of the “example and authority of touch,” instead he promoted reasoning in the gestural sphere when all the body workers who initiated the somatic education era advocated to dissolve the reasoning mind into feelings.

To analyze the conditions of use present (it would be far clearer to say, “to analyze the conditions of coordination present”), to select the means-whereby of a more satisfactory coordination and to project a series of orders of movements at the same time, Alexander indicated in no uncertain terms that the reasoning processes must be trained, their addiction to feeling must be regulated, the habit of instinctively seeking the easy way[8] —seeking what feels right immediately and refusing to reason from a wide perspective— must be curbed.

When Alexander changed his general use (general coordination of the movements of all the parts of the torso) he was working with his reflexion (reasoning) based on what he had seen of the wrong movements which animated his reflection (visuospatial cognition) in the mirror. These activities were not separated. He was not interested and even less guided by what he felt: he combated his self-hypnotic tendency with controlled experiments in which he ordered the movements of his reflection (image in the mirror) to see what he was really doing with the different parts of his torso. I cannot see why we should not do what he did in our lessons.

Anyone can do what I do, if they will do what I did. But none of you want the discipline. (Alexander, F.M.; Aphorisms, (London: Mouritz, 2000), p. 76.)

In actual fact, a video recording of an ‘evolution’ (an experiment of conscious guidance in practice) is a much better subject to train the pupil’s capacity of analysis, reasoning out and creation of decisions in action than an image seen fleetingly in a mirror. Planning and performing series of movements in front of a camera and observing later how the evolution unfolded is perfect to learn to cease to rely upon feeling and in its place, employ the reasoning processes to make decisions and progressively implement the actions promised.

In the work that followed I came to see that to get a direction of my use which would ensure this satisfactory reaction, I must cease to rely upon the feeling associated with my instinctive direction, and in its place employ my reasoning processes, in order

1. to analyze the conditions of use present;

2. to select (reason out) the means whereby a more satisfactory use could be brought about;

3. to project consciously the directions required for putting these means into effect.

In short, I concluded that if I were ever to be able to react satisfactorily to the stimulus to use my voice, I must replace my old instinctive (unreasoned) direction of myself by a new conscious (reasoned) direction.

(Alexander, F.M.; The Use of the Self, Its Conscious Direction in Relation to Diagnosis, (Third Ed. Centerline Press 1946), p. 17)

The whole idea of directing according to a ‘correct feeling’ —all the separate feelings coalesced into a group of correct feeling directions— is just presenting the coordination of movements upside down.

The pupil as an actor of conscious guidance

Imagine the actor who decides to work with and change the manner of use of his reflection. Say he wants to look tall and wide in a standing gesture, i.e., that he wants to project an image so organized that its stature does not look short and narrow to the public, especially when this is his habit of reaction in difficult situations or when he makes unusual demands to his mental and physical organism. How does the actor know that it is not his habit to stand tall and wide at the ‘psychological moment’ if he has not seen his reflection—if he has not noticed on video that every time he comes to a difficult passage, he reacts in the same idiosyncratic way by performing unknowingly the same series of bad movements?

Now the interesting thing is how much confidence a teacher places in the capacity of growth of the intelligence of his actor/pupil. After having seen himself do the wrong movements at the same psychological moment, and recognizing that he did not feel any of it, do you think that, in the words of mister Smith “the pupil will always have to rely on mirrors, cameras, and observers to correct misuse?” My guess is that this comment is a tragic underestimation of the real depth of the pupil’s intelligence. Having reasoned with objective visuospatial clues, the actor/pupil will not forget that, in certain circumstances, he does invariably do wrong movements without feeling any of it: he will apply his technique of coordination in anticipation and he will not forget his decisions because he is not occupied at “trying to feel” whether he is “right or not”.

The procedures of the technique of change should not be designed to make the actor/pupil feel the right thing, but to create difficult conditions where he goes wrong constantly, so that he can SEE how he coordinates different movements to assume his habitual pulled down shape, and start to reason about it and about new means-whereby concerted movements which could lead to a different outcome. He would not need to be alerted by a feeling that something is amiss and that he is doing something when he believes he is doing nothing: he would just apply his technique of prevention!

Does he need to be made to feel what it would be like to be tall and wide before starting to work on his impersonation? Does he need to feel what it is to release here or there before projecting a new coordination? It would be a waste of time because what the actor needs is NOT to evaluate his situation by feeling but (A) to consider the habitual series of movements, i.e., the habitual coordination of movements, which make his reflection shorten and narrow [employ his reasoning process to analyze the conditions of use present], and (B) to make the reasoned decision to stop ‘doing’ these movements with orders of definite inhibition, and, at the same time (C) to consider which new concerted movements, i.e., which means-whereby he thinks could contribute to the new conditions he is wishing for his reflection and (D) to start making the decisions to continue to do these simultaneous movements at the moment he feels nothing wrong immediately, but nevertheless is the same moment when he saw himself go wrong on film in the previous experiment (E) then check later and objectively whether he has been able to follow on his concerted decisions at the psychological moment (the moment at which his reaction was seen to be wrong in terms of movements, i.e., the moment at which he felt most and for that reason, the moment at which his thinking dissolved into feeling) and (F) also to check that his new decisions of concerted movements of all the different parts of the torso make effectively his reflection lengthen and widen [employ his reasoning processes to reason out the means-whereby a more satisfactory use could be brought about]. He could then observe his concerted movements to check and see on the video if he has maintained these new decisions in the face of all the feelings that would tend to occupy his mind and make him forget his conscious pledge when on stage [employ his reasoning processes to project consciously the directions required for putting the means into effect].

Sharing the story of conscious guidance and control

In the following passage, let’s say that I disagree profoundly with Walter Carrington’s opinion about Alexander’s alleged lack of knowledge or disinterest for ‘mechanisms’ —I will come back in length about this— but I find his portrayal hugely revelatory regarding the subject at hand and the apparent incapacity of modern Alexander technique teachers to conceive the existence of ‘conscious reasoned guidance’ detached from ‘sensory guidance’. As you will see, it all comes down to the absence of shared experience.

He (Alexander) did not know anything about mechanisms. And furthermore, he was not interested in mechanisms, because he did not have to be. Because unlike us, you see, what he had done was this: he had used a mirror and instead of paying attention to himself [Walter touches the pupil’s shoulders indicating his body] to this fellow here [Walter places both his hands on the pupil’s shoulder], his attention was focused on that fellow there [Walter indicates with his hand an imaginary mirror]. And when he was directing and ordering and so on, he was looking at the effect on that fellow there. He knew what he wanted that chap to do. He was not concerned with this chap [he takes the shoulders of the pupil with both hands], you know what I mean. And, of course, that meant that in a practical way he did not have to ask what is the mechanism of the head balance or what the mechanism of posture and so on because he was able to see in the mirror that certain things took place and it interfered with the breathing and it interfered with balance and it interfered with his neck whereas if other things took place then there was evident improvement. He did not need to ask any question because it was perfectly obvious that the thing was working better. (Carrington, W.; Two private lessons with Walter Carrington, 1997, 8min37sec —Masoero, J.; Transcription from the DVD).

Unlike us, trained teachers of STAT or of other societies, what Alexander had done was to stop paying attention to himself —stop paying attention to his feeling self—, and focus his attention on ‘this fellow there’, the reflection (the image of himself) in the mirror. When he was planning a series of movements, directing, ordering and so on, making decisions[9] of concerted movements instead of programming to do kinesthetically what he felt to be right, he did not need the material gleaned through his kinesthetic sense[10]: he just had to remember what he had seen himself do in the mirror with a trained eye to model the new result of those processes of guidance he instigated with verbal orders of movements. He had reasoned out orders for various synchronized movements he did not want to give consent to and other orders for concerted movements he wanted to give consent to.

“If you do anything to affect the processes, you must do something that will affect the results of those processes” (Alexander, F.M.; in Fisher, J.M.O, Articles and Lectures, 1995, Teaching Aphorisms, p. 202)

If you do anything to affect the processes of guidance, you must do something that can be objectively registered as an effect of your order. Alexander knew by reasoning what he wanted ‘that chap’ to do (the reflection/image) and he was not concerned with ‘this chap’ (the old feeling self). When Walter says that Alexander knew what he wanted his reflection-in-the-mirror to do, he is not saying that he “knew kinesthetically” what the gesture should feel like, absolutely not.

“Any fool can do the thing he wants to feel —there is no trouble about that. The difficulty is to make him feel that he does not want to feel”. (Alexander, F.M.; in Fisher, J.M.O, Articles and Lectures, 1995, Teaching Aphorisms, p. 197)

When you film your performance of a procedure requiring the conscious guidance of a series of movements, the difficulty is to make you feel that you do not want to feel but to continue with the reasoned orders of movement no matter how wrong you feel —you never know what your reflection/image will reveal in the video recording later. You must plunge in the dark and assume that your sensory appreciation may yet be proved wrong one more time when visioning the video recording. Yet, this uncertainty principle does not imply that it is difficult to imagine which planned movements could bring into play a new use of certain parts, i.e., new concerted movements of different parts of the reflected torso which produce indirectly a lengthening and a widening of the reflected torso as a whole, a reduction of the reflected protruding abdomen concomitant with a complete reduction of the reflected thoraco-lumbar curve. Similarly, this is not difficult to plan as long as you accept that these reflected consequences (in the video-recording) will involve sensory experiences which are totally unfamiliar and which will feel “wrong”.

I now set out on an experiment which brought into play a new use of certain parts and involved sensory experiences that were totally unfamiliar (Alexander, F.M., “*The use of the self*”, Integral Press 1932, reprinted 1955, p. 10).

When you suspend the sensory evaluation of this-chap (your feeling mind) during the process of projecting your series of orders, after having finished to allow the processes of guidance to be dominated by your reasoning (conscious mind) through the ordering of the movements you want to appear in your reflection-in-the-video-recording, you can later watch the performance of that reflected-chap, and you will discover whether the result of those processes have been affected or not, in the structure of the anatomical image projected on the screen.

Conscious guidance is defined by the means-whereby principle, a new use of the conscious mind to project a series of orders of movement to the different parts of the torso in order to obtain the primary movement, i.e. the harmonic expansion of the torso. Without this possibility of “doing according to the means-whereby principle”, there is no fundamental getaway to the problem of constructing a new coordination while affected by a faulty sensory appreciation (how could Alexander change his coordination from wrong to right when he was affected by a faulty sensory appreciation?).

My experiences, therefore, convinced me that in any attempt to control habitual reaction the need to work to a new principle asserts itself, the principle, namely, of inhibiting our habitual desire to go straight to our end trusting to feeling for guidance, and then of employing only those “means-whereby” which indirectly bring about the desired change in our habitual reaction—the end. (Alexander, F.M.; The Universal Constant in Living, (Third Ed. 1946).pdf, p. 23)

We can start to form a preliminary answer, at least a negative one, to the question of what are “only those means whereby which indirectly bring about the desired change in our habitual reaction—the end”: any conception of movement, or of any condition of the self gained through kinesthesia cannot be part of the conscious means the initial Alexander technique is providing. When you know what you want that chap (your reflection) to do, you also know that what you have felt today in guiding your reflection to that condition, will feel totally different tomorrow. The knowledge of conscious guidance is not a feeling or somatic knowledge at all.

In conclusion

Obviously, any new movement in a series, any new part of a coordination of a series of movements, that is not repeating the history of his system is going to feel “wrong”, to require ‘conscious work’ to be constructed inside a series of movements and, if the pupil has the tendency to judge whether experiences of use are right or not by the way they feel, it is almost certain that he will balk[11] at employing the new coordination. If he is not checking on a video recording that he is indeed maintaining his decisions to project the directions required for putting the means into effect, he will believe he has done so, when in actual fact, he has not. This work is essential for the pupil to build his confidence in his conscious mind.

I am teaching my students not to trust to feeling for the evaluation, for the readjustment nor the direction of their use. It is the cornerstone of the lessons of conscious guidance and control through reeducation, readjustment and coordination[12]: the establishment of a “normal kinesthesia” is not the means to the end, but just a by-product of the process of training. This explains why I say that the initialAT is an “anti-somatic” teaching.

As the reader knows, I had recognized much earlier that I ought not to trust to my feeling for the direction of my use, but I had never fully realized all that this implied—namely, that the sensory experience associated with the new use would be so unfamiliar and therefore “feel” so unnatural and wrong that I, like everyone else, with my ingrained habit of judging whether experiences of use were “right” or not by the way they felt, would almost inevitably balk at employing the new use. Obviously, any new use must feel different from the old, and if the old use felt right, the new use was bound to feel wrong. I now had to face the fact that in all my attempts during these past months I had been trying to employ a new use of myself which was bound to feel wrong, at the same time trusting to my feeling of what was right to tell me whether I was employing it or not. This meant that all my efforts up till now had resolved themselves into an attempt to employ a reasoning direction of my use at the moment of speaking, while for the purpose of this attempt I was actually bringing into play my old habitual use and so reverting to my instinctive misdirection. Small wonder that this attempt had proved futile !(Alexander, F.M.; The Use of the Self, Its Conscious Direction in Relation to Diagnosis, (Third Ed. Centerline Press 1946), p. 21)

The problem is not to feel “right” or to feel the “right thing”, but to start making decisions which count regarding your reflexion. Or is employing a ‘reasoning direction’ not the Alexander technique?

I have never witnessed a pupil who had retained a good habit of general use by “working on the sensory side”, i.e., by having a series of lessons of the modern Alexander technique. The expert somatic teacher can communicate what he thinks is a correct sensory experience to the pupil all he wants with his expert hands-on, but what the pupil will develop out of that somatic and unreasoned event on his part is not a good habit of “making decisions instead of doing kinesthetically what feels to be right”. What such somatic lessons do is that they lead the pupil to overcompensate on the feeling side, to believe he/she can feel the “right thing” and to develop a form of herd-superiority complex which does not help at all to engage in continuing experiments and discover new activities in which the reaction is not at all appropriate and begs to be changed. They certainly do not help develop the reasoning processes out of the feeling morass in which they are encrusted.

A good general use is not a person’s possession, an assurance or a promise of doing everything right and of feeling the right thing: it is instead the growing ability to reason on our feet and find new problems of use to lift our brain out of the groove. The tendency to adhere to sensations, to evaluate everything in terms of sensations, to think that movements are defined by sensations is what Alexander calls the ‘preliminary inertia of mind’.

And in all such efforts to apprehend and control mental habits, the first and only real difficulty is to overcome the preliminary inertia of mind in order to combat the subjective habit. The brain becomes used to thinking in a certain way, it works in a groove, and when set in action, slides along the familiar, well-worn path; but when once it is lifted out of the groove, it is astonishing how easily it may be directed. At first it will have a tendency to return to its old manner of working by means of one mechanical unintelligent operation, but the groove soon fills, and although thereafter we may be able to use the old path if we choose, we are no longer bound to it. (Alexander, msi, “Habits of thoughts and of body, p. 63”)

What is the essential solution for Mister Smith is the first and only real difficulty for the initialAT.

[1] This is pure plagiarism. See Sir Ken Robinson, The Element 15m45s, 2015.

[2] Trevelyan, G., MacInnes, G.; The Alexander society Bulletins and letters, 1936.pdf, p. 8.

[3] “The substitution of control by intelligence for control by external authority, not the negative principle of no control or the spasmodic principle of control by emotional gusts, is the only basis upon which reformed education can build. To come into possession of intelligence is the sole human title to freedom” (Dewey, J., in Alexander, F.M., “Man’s supreme inheritance”, Chaterson Ltd 1910, reprinted 1946, p. xxi).

[4] Co-ordinated use of the different parts during any evolution calls for the continuous, conscious projection of orders to the different parts involved, the primary order concerned with the guidance and control of the primary part of the act being continued whilst the orders connected with the secondary part of the movement are projected, and so on, however many orders are required (the number of these depending upon the demands of the processes concerned with a particular movement). (Alexander, F.M., “*Constructive conscious control of the individual*”, Integral Press 1923, reprinted 1955, p. 167, “Projection of Orders”)

[5] Alexander, F.M.; The Use of the Self, Its Conscious Direction in Relation to Diagnosis, (Third Ed. Centerline Press 1946), p. 36

[6]I claim that the primary requirement in dealing with all specific symptoms is to prevent the misdirection [of all the movements of the different parts of the mechanism of the torso] which leads to wrong use and functioning, and to establish in its place a new and satisfactory direction as a means of bringing about an improvement in use and functioning throughout the organism.

This indirect procedure is true to the principle that the unity of the human organism is indivisible, and where there is an understanding of the means whereby the use of the mechanisms can be directed in practice as a concerted activity, in the sense I have tried to define, the principle of unity works for good.

But there is a reverse side to the picture. It is in the nature of unity that any change in a part means a change in the whole, and the parts of the human organism are knit so closely into a unity that any attempt to make a fundamental change in the working of a part is bound to alter the use and adjustment of the whole. This means that where the concerted use of the mechanisms of the organism is faulty, any attempt to eradicate a defect otherwise than by changing and improving this faulty concerted use is bound to throw out the balance somewhere else. (Alexander, F.M., uos, 1932, p. 30)

[7] “My next instance —namely, “relaxation”— is even less efficient [than physical culture and muscle tensing exercises]. The usual procedure is to instruct the pupil, who is either sitting or lying on the floor, to relax, or to do what he or she understands by relaxing. The result is invariably collapse. For relaxation really means a due tension of the parts of the muscular system intended by nature to be constantly more or less tensed, together with a relaxation of those parts intended by nature to be more or less relaxed, a condition which is readily secured in practice by adopting what I have called in my other writings the geometry [position] of mechanical advantage.

From an incorrect understanding of the proper condition natural to the various muscles, the theory of relaxation, like that of the rest cure, makes a wrong assumption, and if either system is persisted in, there must inevitably follow a general lowering of vitality which will be felt the moment regular duties are taken up again, and which will soon bring about the return of the old troubles in an exaggerated form. (Alexander, F.M., “Man’s supreme inheritance”, Chaterson Ltd 1910, reprinted 1946, p. 15).

[8] I have found them particularly difficult to teach because of their over-excited fear reflexes and of their habit of instinctively seeking the easy way, even when admitting that it is not the best for their purpose. They are self-hypnotic to a high and harmful degree, and find the inhibition of habitual reaction much more difficult than most other pupils. Until their manner of use has been improved, which means that some reconditioning has been effected, it is almost impossible to get them to use their reasoning processes in trying to understand new “means-whereby” to their ends. One of them actually said: “I don’t want to understand what I am doing.” He really meant that he had no desire to use his will-to-do in carrying out consciously the new procedures he had decided were to his advantage.

(Alexander, F.M.; The Universal Constant in Living, (Third Ed. 1946).pdf, p. 163)

[9] “You are not making decisions. You are doing kinaesthetically what you feel to be right” (Alexander, F.M.; in Fisher, J.M.O, Articles and Lectures, 1995, Teaching Aphorisms, p. 196)

[10] “The material with which we think is that which is gleaned through the senses. The only way in which we can conceive of movement, or of any condition of the self is through kinesthesia. The only way in which we can plan and execute movement is through sensory imagination”. (Smith, Lawrence; Alextech-list, March 10, 2008)

[11] The sensory experience associated with the new use would be so unfamiliar and therefore “feel” so unnatural and wrong that I, like everyone else, with my ingrained habit of judging whether experiences of use were “right” or not by the way they felt, would almost inevitably balk at employing the new use (Alexander, F.M.; The Use of the Self, Its Conscious Direction in Relation to Diagnosis, (Third Ed. Centerline Press 1946), p. 21).

[12] “The first principle in all training, from the earliest years of child life, must be on a conscious plane of co-ordination, re-education, and readjustment, which will establish a normal kinaesthesia”. (Alexander, F.M.; Man’s Supreme Inheritance (Third Ed., 1946), p. 42)

I can imagine the struggle one would have after training in the mAt, and getting the experience of years and years of teaching in this manner serving as a strong basis/belief of its “rightness”. However, if you just take at least a few lessons in the iAt (I had only 2); it’s hard to believe one would fail to appreciate the truth of this different manner of understanding/teaching the Technique. By principle, the Technique taught by Alexander would actually make you quite willing to face your own shortcomings and mistakes (feeling wrong) and even more so willing to change or adopt new ideas that have come to prove itself worthy in the practical sphere. In my opinion, your approach has made the AT world richer and stronger.

“Planning and performing series of movements in front of a camera and observing later how the evolution unfolded is perfect to learn to cease to rely upon feeling and in its place, employ the reasoning processes.”

Though I did learn this ‘lesson’ while playing with the fleeting image of myself in the mirror after my two first lessons; there has been nothing in my previous experience of the AT that had made such a strong impact on my overall attitude in such a simple way; repeating the disconcerting conscious act of relying on my feeling sense to put into actions concerted movements of the parts of the torso and witnessing the huge gap between feelings (what I felt was taking me in the correct realization of my preconceived gestural plan) and reality (what I was seeing in the mirrors); simply meaning that if I were to follow my feelings in the work of correcting my own coordination; I’d be doomed to fail forever!

Am I willing to trust a feeling sense that cannot help me turn a consciously intended gesture into its physical realization? Am I willing to trust that same feeling sense in the act of judging what is right in all the other activities of my life?

The more I practice, the easier it is to detach myself from habitual reactivity; thinking loops, learned beliefs or emotional habits; that is nothing but expression of my own faulty sensory appreciaiton; coming back to reality; analyzing the conditions present; reasoning the means whereby I may reach my end, and following up with actions while “sticking to my decision against the habit of life.”

It’s all already there in the practice of conscious guidance and control taught by Jeando Masoero.

I find it interesting how often you quote Alexander and how you seem to adhere closely to the intellectual framework he sets forth in his writings, but you reject his teaching methods. Yet his teaching preceded his writing and does not seem to have been altered by the development of his ideas as expressed in his books. I don’t think that one could reconstruct Alexander’s means of teaching from reading his books, and I don’t believe the loss of his books would negatively impact the teaching as passed down from him directly. He certainly did not write to explain the practical aspects of his teaching. He seemed to write to take ownership of his teaching (the doctor who first engaged Alexander to teach in London was claiming ownership of the work), and to position himself as a thinker and innovator, as well as to market his work.

I suffered a number of crippling injuries in my performing career and was diagnosed with cervical arthritis, arthritis of the hands, herniated disks, chronic bursitis in knees and shoulders, and multiple tendinitis. Doctors, physiotherapists, acupuncturists, etc. , were of little help. Nor were my workshops with Marjory Barstow, which I found quite superficial. However, hands-on Alexander Technique lessons with qualified teachers restored me to high functioning. At age 68 I have no pain in any joints, muscles or tendons, and I run (barefoot), ski, and swim with great pleasure.

http://www.alexandertechnique-running.com/hands-on-work-in-the-alexander-technique/

Hi Lawrence,

Sorry for the late reply but I was engaged elsewhere and I forgot about the website comments, so I did not see your questions.

I was attracted in the first place by the Alexander technique because of the books Alexander wrote, and particularly by his concept of conscious guidance and control.

I was fascinated by the development of the ‘conscious mind’, i.e., how the young Alexander could have changed his own use without any external intervention, and I was interested sufficiently to train with STAT UK. From the start I wanted to discover what he meant by “restoring and maintaining in activity a reasoning direction of the use of the mechanisms”, but I also translated the four books into French. This is how I started to notice that Alexander had developed two techniques and not one: first a technique of reasoned conscious guidance he used for himself and a few others, and, much later, another technique based on irreconcilable principles, i.e., a technique of subconscious (somatic) guidance which does certainly help some people feel better and cure some others of their pains, but does not help to escape from the subconscious plane.

I had lessons with all the first generation teachers I could find in London during my training, I asked them questions after questions about what Alexander had written, but I finished qualifying as a ‘modern Alexander touch-teacher’ utterly dissatisfied because no one had any interest for or much understanding of the principles of conscious guidance and control, thinking that the technique is fully contained in hands-on experience. Interestingly, not all of the first generation teachers I met tried to dissuade me to question further, and some even encouraged me to explore. This is why I started to experiment, to see whether with Alexander’s indications it was possible to teach oneself conscious guidance in a way similar to what Alexander had done with himself. This explains why I follow Alexander in theory but not in his late practice. By the way, do not think that this change has been easy: putting hands-on people is really addictive and it took me a long time to wean myself of the touch-teacher lifestyle.

At the time (1910) of the writing of the first book and the libel case with Dr. Spicer, there is no mention of ‘expert manipulations’. Alexander is talking about re-education of the mind, resenting the fact that Spicer compares him with an “hypnotist” (Alexander, F.M.; A protest against certain assumptions contained in a lecture delivered by Dr. R.H. Spicer). It is strange that Spicer does not compare him with a bonesetter or a physical therapist if he was already manipulating people into the correct pose. If you take the time to read with an open mind you will see that Alexander is saying that the pupil can insure a posture specifically correct for himself without being conscious of what that posture is. Does this not explain how Alexander could have changed his use? Does it not remind you of “reasoning from the known to the unknown”? I know that you will be tempted to read “the teacher must himself place the pupil in a position of mechanical advantage” as an indication that Alexander is organising the different parts of the anatomical structure of the pupil with his hands, but I have two questions to ask. How did Alexander teach himself his technique? Why would he say that, by the mere rehearsal of orders, it is the pupil HIMSELF who can insure a posture when he is not conscious of what that posture is? If he is not conscious of what that posture is, it means that Alexander has not established the movements for him, exactly as Alexander could not have been conscious of what the posture specifically correct for himself was when he worked with himself in front of his mirrors.

Anyway, I felt there was a case to explore further and experiment despite the constant “opposition” I received from all the modern Alexander teachers in the last twenty five years. I understand this opposition by the way. I realise that I am disturbing the consensus.

Hello Jeandro,

I would like to apologize for comments I have made on forums related to your work. I have since listened to your interviews with Mastaneh Nazarian and I was most impressed, both by your intelligence and by your presentation. I have come into conflict with some on the A.T. forums who teach online lessons and have never themselves trained to teach the A.T. I very wrongly associated you with these application approach teachers, most particularly those whose only A.T. experience was group workshops with Marjory Barstow.

As I mentioned, I have taught traditional hands-on A.T. lessons for over 30 years, and I think I have helped many people to recognize and to alter behavior that was limiting for them. Hands-on lessons were a life-saver for me. I have never encountered someone who has reasoned in such depth about the theory behind A.T., and I just want to say that you have my respect. I can’t say you have my agreement, because some of what you say is a bit beyond me. I will continue to read you and listen to you.

I’m very sorry for my bad behavior!

Lawrence