This series of questions was asked via email, after a third lesson, by a new pupil who is not a teacher (nor a student of a training center) of the modern Alexander technique. You could say he is a “lay person”, a person who does not have specialised or professional knowledge in the subject. Very often, a beginner will ask questions which throw light on words we often use without being very clear on their meaning. I have slightly changed my answers from the original to make them more general.

1. What do you mean by dynamic?

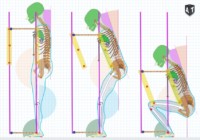

The goal of the performance of a series of Orders of movements of adjustment is to obtain a geometry of mechanical advantage of the whole mechanism of the torso. This end-geometry1 can be seen as either static or dynamic. Dynamic refers to the concept of motion

, that is, a movement of the torso as a whole as in standing up from a chair, leaning forward or back with the torso, squatting, walking, running, etc.

As we will see in the next answer, a dynamic gesture brings to the fore the whole equilibrium of the self and, obviously, it emphasises our more or less incorrect “sensory” perception of our own equilibrium.

2. How long should the rulers be?

The most useful length is between 20 and 25 inches long.

The rulers have to be light and stiff so that they can be used as “unit of measure” against a vertical wall or any other surface of reference.

Some times a shorter ruler can be useful to measure the line of Wholeness close to a wall, especially in dynamic gestures (it is then best to equip the ruler with a wheel at one end to allow for a smooth acceleration of movement).

Poise can be controlled objectively in activity using a wheeled ruler. Such a procedure does not lie, it separates the wheat from the chaff and establishes beyond doubt whether you know how to create and use antagonistic pulls or not.

The line of wholeness

is an imaginary vertical line (a line in space that no one can feel) which connects the top of the frontal part of the torso with the front of the ankle.

After studying many pictures and short films of Alexander’s, I started to form the notion that Alexander was indeed using the geometrical tools invented by Delsarte thirty years before to command reasoned dynamic gestures.

Alexander appears to have solved for himself the gestural problems set by Delsarte2, that is, in this case, how to lean with the torso while keeping the throat on top of the front of the ankle without endangering his equilibrium nor the harmonic expansion of the torso. The geometrical characteristics of Alexander’s gestures, in particular the constant angle of the torso to the vertical from “monkey” to “squat” as they can be measured on still pictures at various times of his life are too strict to be mere chance happening.

I found that using the length of a ruler and a wall, it is deceptively simple to control whether the front of the upper part of the torso (throat spot) is vertically aligned on the front of the ankle (instep spot) during the whole gesture from standing to squat and back again: if both bony spots are at the same distance from a vertical wall, then it follows that they are exactly on top of each other.

This gesture which keeps the (throat spot) on top of the (instep spot) is so out of the ordinary, so counter-intuitive— because it feels so “wrong”, so “out of balance”—that it cannot be a spontaneous, embodied cognition achievement. Only as the individual’s reason is reached can the series of instructions of movement be made effective, so that the gesture is purely passive and elastic, poised and dynamic. If the subject of such experiment does not know how to get the antagonistic pulls working3, there is no way he can “keep his balance” during the gesture (as Alexander proved he could), let alone maintain the angle of the torso to the vertical.

3. Why can the rib at the back of the armpit only be located after following the procedure we did to locate it? I’m not exactly sure that I connect with the correct part of my rib cage when I do this, how can I be sure that I am connecting with the part you have in mind?

The procedure you followed in our lesson ensures that the arm and shoulder are in the correct relationship with the torso so that you could find the required spot of the side of the ribcage with sufficient precision. It is impossible to place the Base-of-the-Palm spot on top of the opposite Base-of-the-Thigh spot without widening the upper back and lowering the shoulder were we want it to be.

There is another procedure (best done with outside help) to place correctly the Rib-at-the-back-of-the-Armpit spots which I describe likewise:

This is one of the procedure proposed to locate the anatomical landmark (spot) that we use do consciously guide the series of movements of the different parts of the mechanism of the torso.

In standing, looking sagittally at the torso (see picture)

- place a flat ruler on the Rib-8 Line beneath both elbows so that the ruler is ninety degree to forward,

- place the palms of both hands on the upper thigh and

- pull the Tip of the Elbow spots outward AWAY FROM the Throat spot (without raising the palms which will move the shoulders down relatively to the ribcage) and away from the palms,

- pull the palms Backward & the Upper-Part-of-the-Arm spots Forward until the Iliac spot and Rib-8 spot are aligned vertically above each other,

- place another ruler under the Armpit to assess the height of the Armpit,

- place a ruler vertically on the side of the ribcage and press it forward until it bumps against the back of the top of the upper arm bone (humerus).The upper front of the intersection of the two rulers is the Rib-at-the-back-of-the-Armpit spot. Using a pointed object, locate the spot on the side of the ribcage which is just underneath the upper forward quadrant drawn by the cross of rulers.

Now, knowing your embryonic precision in directing your mind to spatial targets at this time, you do not need this type of accuracy. I am just providing a different procedure to settle your mind and have you explore other aspect of guiding the self with reasoned instructions (discipline). If you just locate a spot at the height of the armpit roughly in the middle of the side of the ribcage, this will be perfectly fine.

This spot, however accurate it is for the moment, is really useful to direct the mind to the making of the decisions to move BACK every spot that is below the Armpit line (including the Rib-at-the-back-of-the-Armpit spots) and everything that is above the Armpit line FORWARD. In my mind, this combination of movements corresponds exactly with the instructions Alexander was using Moving the back back and moving the upper torso forward

during the 1931 training course.

4. What do you mean by geometrical disposition?

A geometrical disposition is a way to reason about the movements of the parts (particularly the parts of the mechanism of the torso but not only as you will see in other lessons).

A subject sitting on a chair is seen consciously measuring, that is controlling consciously the effect of a series of concerted movements of the different parts of the torso.

In our lessons, the movements of the parts are conceived as concerted movements of several anatomical landmarks—bony spots— which can be represented in geometrical diagrams and measured after the projection of movements has been performed.

On this image, the geometrical disposition of the spots at the front of the torso is checked using rulers of the same length which measure

the position in space relatively to an external reference (straight wall plane).

If the spots are at the same distance from the wall, that is, if the subject can (A) place the rulers in contact with the wall and the spot of the bony parts and (B) make sure that the rulers are parallel, we can reason that they are vertically align relatively to each other.

On this picture, it can be measured that three spots at the front of the torso are aligned on the same plane. This line which measure the movements of the different parts of the torso is called “line of Unity” by Delsarte. I am using it to establish a reasoned guidance and control of the movements of the parts of the torso in space. In this way, the different movements of the parts have not only to establish definite relations between the parts, but also relations between the spatial location of the parts and and an external reference (a vertical wall).

When I started to read Delsarte in this way, I was astounded to see

- that the head and neck were moving forward and up without any attempt at guiding them and,

- that the general shape of the head, neck and torso started to display exactly the same proportion as Alexander demonstrate in all his pictures.

5. What spot is the 3rd rib and how do I locate it?

I should have said the front of the upper torso ribcage

. The front of the first rib is exactly at the height of the Throat spot. It is not possible to feel with the finger the first rib (it is beneath the clavicle bone), but the second, third and fourth ribs are easy to touch at the front of the upper torso.

6. What do you mean by dexterity?

The best answer will come from studying Bernstein (N.A.). All my understanding of the concept of dexterity comes directly from reading him.

Where and How Does Dexterity Reveal Itself?

In the first introductory essay, we gave an initial, very general definition of dexterity: a motor ability to quickly find a correct solution for a problem in any situation, that is, to exhibit motor wits in any conditions. I ask my readers to set aside this definition for the time being and to rely on their feelings for the language and meaning of the words. Let us consider how appropriate or inappropriate it would be to describe the movements in the following examples as dexterous. A sprinter is running along a track. He has passed all the competitors, his strides are long, all the movements are impeccably beautiful, and deepest analysis proves their rationality and expediency. Can this example, which exemplifies pure perfection, be described as dexterous? Probably everyone would agree that the answer is no.

The word dexterous somehow sounds awkward. This beautiful movement lacks something that could be judged as dexterous. Let us consider the next example: >He needed to reach the forest edge faster than his enemies. The enemies tried to cut him off from the trees, shooting while they ran. It was hard to run. The field was full of shallow ditches. Once he nearly fell down after slipping on the wet grass. His boots were smeared all over with mud. But all his senses tightened up. Looking under his feet, he sometimes threw a glance at the enemies, guessing their next moves and simultaneously planning the next 10 meters of his run. At last, he flew like a bird over a ditch hidden behind the bushes and got beyond the edge of the forest. No one would hesitate to say that the soldier’s life was saved exclusively by his dexterity.

What is the essential difference between this example and the first one?

In both cases, the movement was running. However, comparing these two cases, we come to a conclusion that dexterity apparently is not in the motor act itself but is revealed by its interaction with the changing external conditions, with uncontrolled and unpredicted influences from the environment. Running, by itself, is not dexterous, but the way the runner adjusted the movement for solving a certain externally posed problem is. These examples were not chosen accidentally. Regardless of the kinds of movements we might consider, the capacity of dexterity appears to be, not in the movements themselves, but rather in their interaction with the environment. The more complex and unpredictable the interactions are, the more successfully a person overcomes them, the higher is the dexterity of those movements. That’s why we are fascinated by the dexterity of the labor movements of a skilled worker who is very efficient, and objects seem to be born by themselves under his hands. But no one would describe as dexterous very similar movements made by empty hands as, for example, when playing charades. For this reason, plain running along a track does not look dexterous whereas running with hurdles sometimes provides keen examples of dexterity.

For this reason, simple walking turns into an act of superior dexterity when performed on a narrow ledge, for example, during a competition in mountain climbing. For this reason, running on hands and feet on a floor is not only far from being dexterous but rather resembles its antonym, clumsiness, whereas running on hands and feet up a rope ladder requires high dexterity. If a ship’s boy climbs a bending mast in pounding rain, with the rope ladder swinging like a cobweb, one witnesses dexterity in its highest expression. So, the first of the established essential features of dexterity is that it always refers to the external world.

How Does Dexterity Work?

We have understood the requirements for the outcome of dexterous movements and actions. We may expect them to solve the problem correctly, that is, adequately and accurately, quickly and successfully. Now is the time to pose another question: What are dexterous movements and actions? How does dexterity attain its results?

There is an old story about a huge boulder. It was sitting in the middle of the central square of a town for ages. The magistrate announced a competition on how to get rid of it. One bidder decided to build a huge platform on rollers and drive the boulder away and asked for 1,000 rubles. Another one suggested exploding it into pieces with dynamite and assessed the expenses at about 700 rubles. A peasant who happened to be nearby said:

I will get rid of the boulder for 50 rubles.How???I will dig a hole by its side and push it into the hole. Then I will level the ground all around the square.That was what he did and got 50 rubles for the work and another 50 for a smart solution. This short story presents a very good example. The boulder could have been removed by any of the suggested methods, and each method would also have taken approximately the same time. However, the advantages of the third project were simplicity and cheapness. One can find many examples of a correct result obtained quickly but with an enormous expenditure of time, effort, tool wear, and so forth. All such actions are well described by the expression,Shooting sparrows with a cannon.Baron Munchausen suggested the well-known project of plowing the fields by first burying truffles at even intervals and then by letting a herd of pigs into the field who would plow it by digging the truffles out.Rationality is the first condition of dexterity

If a woman asks her inexperienced husband to peel a potful of potatoes, she is likely to find a handful of perfectly clean potatoes the size of a walnut, a heap of peelings, and a destroyed pocketknife. All these funny and not-so-funny examples reveal to us that, in order to be called dexterous, movements and actions must not only lead to a correct result but also do so rationally. This rationality is the first condition in answer to the question of how. We have already decided that sprint running along a plain track does not have the prerequisites of dexterity. As shown by precise measurements, everything is sacrificed for the sake of speed during a sprint. The movements of even the best sprinters are not very rational. Experience shows that the body cannot squeeze reasonably well-constructed and economic movements into those fractions of a second, which are being spent for each step. According to scientific data, this is likely to be the main reason that it is so difficult to beat the world record (10.2s for a 100 m race): At such super high speeds, the cost of movements increases at an outrageous rate. The situation is different for running over longer distances. Here, the task is not to show the highest possible speed but to maintain a certain speed for a considerable time. Therefore, rationality and expediency of movements become efficient. (From Bernstein, N.A.; On dexterity and its development, 1969, trad. Latash, 470 pages).

7. Is there anything I can do to put into practice what we have covered in the lessons so far?

This is a funny question considering you have watched the video of your lesson and asked these questions. What you have done is the work which is expected of you, bringing some rationality in your decisions of movements.

In order to be called dexterous, movements and actions must not only lead to a correct result but also do so rationally. This rationality is the first condition in answer to the question of how. (Bernstein, N.A.)

Now that you have your answers, feel free to experiment on your own with all the procedures which you performed during your session with me. Watching the video of your lesson again (and again) will bring new questions and new experiments as for example: I asked you to perform some concerted movements during two seconds and then, to stop all movements. The first question that stands to mind is “where you able to inhibit all movements after the adjustments or not”? A second one is also tantalising: “after completing the movements of adjustments, did the new geometry stay in place or quickly dissolve into collapse again”?

Footnotes

- Geometry or position that is the result of a series of movements of the different parts

- In the ‘laboratory method of instruction’, the student is taught the principles of the art, the instruments and elements are named, the problems are set, and he is required to experiment for himself under the eye and ear of the teacher; he is then shown wherein he fails or succeeds. Only as the individual [reason] is reached can instruction be made effective (Kirby, A.N., “Public speaking and reading, A treatise on Delivery according to the principle of the New Elocution”, 1895, Boston, p. 8).

- What this young lady is doing now is a very difficult thing to do. She is directing her head forward and up from here (Alexander indicates with his hands a part of her back), he knees forward and the hips back, and that the only way you can get your antagonistic pulls. What interest me is to GIVE HER SOMETHING TO DO by MEANS of which she will put this head forward, and the knees forward and the hips back, and so to get the antagonistic pulls working (Alexander, F.M., “*Articles and Lectures”, “Bedford Physical training College Lecture”, Ed. Mouritz, p. 177 – 178).

I’ll enjoy having some fun exploring these geometrical body-points in motion, Jeando. Thanks for sharing. Love to you, Anna and the boys.