————————————question

I’m trying to experiment in my everyday activities with the orders that I know so far but I’m afraid that there’s the possibility of over doing it some times and end up with more muscle tensions than before.

And from what I knew so far, one main goal of AT is to tackle unnecessary tensions so I’m kinda worried about that.

I’m sorry about my not so precise questions but I’m still in the middle between the modern AT and initial AT.

————————————end question

1. General considerations

A few comments are called for before attempting to answer your new question.

First, I want to thank you for asking it and I will take the time to give you a thorough answer, not only for your sake but also to offer others people who may consider having initial Alexander technique lessons the possibility to reflect on the subject with a different viewpoint.

Most students who have had lessons in the modern Alexander technique are deeply impacted by the simplistic somatic ideas which have constituted along the years the core of its advertising efforts and have now become its doctrine. Once they start having lessons in the initial Alexander technique, they have to make great efforts to change their conceptions from a somatic intuitive easy acceptance (“it feels so right that tension should be banned because it is such a bad thing”) to an intelligent, counter-intuitive and balanced reasoning as it is developed by Alexander (in a tortuous way) in his books.

In short, Alexander does not believe in the release of specifics, specific unduly tense region, and in particular, the Neck.

For instance, if we decide that a defect must be got rid of or a mode of action changed, and if we proceed in the ordinary way to eradicate it by any direct means, we shall fail invariably, and with reason. For when defects in the poise of the body, in the use of the muscular mechanisms, and in the equilibrium are present in the human being, the condition thus evidenced is the result of an undue rigidity of parts of the muscular mechanisms associated with undue flaccidity of others. (Alexander, F.M.; Man’s Supreme Inheritance, (Second Ed. Revised, 1918), p. 65)

Behind this little sentence revealing the association between undue rigidity and undue flaccidity, there is the practical idea that if you decide that a symptom of rigidity in one part of the organism must be got rid of, you have to STOP and think in a new way, because if you do something to release that part directly, then you are dealing with a symptom and not at all considering the cause, i.e. the coordination of the movements of all the parts. Releasing one rigid part will do nothing beneficial to change the cause of the undue flaccidity of the other parts which contributed to the rigidity you sought to eradicate.

If there is any undue muscular pull in any part of the NECK, it is almost certain to be due to the DEFECTIVE COORDINATION in the use of the muscles of the spine, back, and torso generally, the correction of which means the eradication of the real cause of the trouble.

This principle applies to the attempted eradication of all defects or imperfect uses of the mental and physical mechanisms in all the acts of daily life and in such games as cricket, football, billiards, baseball, golf, etc., and in the physical manipulation of the piano, violin, harp, and all such instruments. (Alexander, F.M., “Man’s supreme inheritance”, Chaterson Ltd 1910, reprinted 1946, p. 127) The Processes of Conscious Guidance and Control 127″.

Considering the influence of the coordination of all the parts on a specific defect, is it not a strange thing that all the leaders of opinion of somatic STAT have not realised that their flock appear never to feel undue flaccidity, that they always target undue rigidity as the cause of people’s problems?

“The whole organism is responsible for specific trouble. Proof of this is that we eradicate specific defects in process” (Alexander, F.M.; in Fischer, J.M.O.; Article & Lectures, Mouritz, Teaching Aphorisms, 1995, p. 207).

Alexander ’s proposition is for each individual to work with conscious guidance of the whole organism, i.e. the conscious guidance of all the parts of the structure. It is not an easy path because it means subordinating your decisions to a principle, a mental tool which exists only within a related system of concepts, and which does not work because people believe in it, but because they understand it and because they experiment with it. The aim is to learn to coordinate the movements of all the parts, in order to solve specific problems in the process. This process compel us to inhibit reacting, releasing the parts which feel too tense according to what we feel. It compel us to detach ourselves from the feeling sense.

In his perspective, the technique is not a tool restricted to a class of somatic body-workers who want to put their hands on people to demonstrate how unique the gift they possess is, but a social belonging which can help anyone practice experiments of conscious re-education, readjustment and coordination, as long as they accept to take the time to make sense of it and to conduct an inquiry in that direction.

2. Overdoing principled experiments at your stage (2nd lesson)

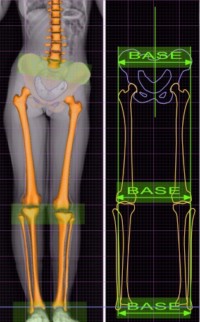

During your last lesson (z = 2), we discussed a principle. It was the principle of establishing a definite distance, i.e. a mental benchmark or guideline (a mental distance that can be used as a standard to compare, judge other similar distances) to organise a series of movements aimed at a common consequence or “end”.

In practice, we established first that to obtain the same measurable distance between two bony parts, i.e. the exterior of the knees and the exterior of the heels, equal to the ‘benchmark distance’ which I called “base” and defined as the width of your pelvis measured between your two palms with a wooden ruler, you had to control consciously two different movements of the knees and heels, simultaneously.

At first, the only tools I gave you to experiment with this coordination task were two verbal orders of movements aiming at a limit, i.e. the benchmark distance. In other words, this simultaneous guidance of the two movements so defined was aptly subsumed by two verbal instructions aimed at obtaining the correct “pose of the feet” and knees at the same time (simultaneously) so that the “torso and limbs could be influenced and aided by the force of gravity”.

Two definite orders of performance were used: “I pull the exterior of the heels outward to “base” and ”I pull the exterior of the knees inward to base“. The information contained in the expression ”pulling something to base“ refer to the psycho-mechanical act of guiding the movements of two bony parts at a definite distance, i.e. ”a base distance” from each other, defined by the width of the upper parts of the ilium bones.

It is difficult to see how you could overdo this experiment. Yet, it is obvious that it will make you feel tensions where you feel nothing habitually. By using the concerted series of directions of movements, you are directing your mind to bring into action some flaccid part which produce no work in your habitual coordination of the different parts of the torso. If you have been made hypersensitive to feelings of tension by your previous training, it is likely that the situation will appear serious, but it will not last long, as when tissues are brought back into action, they quickly develop both in strength and speed and you get used to the new feeling of balanced tension.

To counter-balance your worried reaction to this unavoidable stage, you need to consider

1. the great mental field that you can start exploring. Ask yourself this question: where before have you had the opportunity to train yourself to make a series of decisions, holding these decisions in mind and performing these decisions and no others simultaneously in actual practice with clear guidelines to control your aim with accuracy? Training for simultaneous decisions in activity goes much farther than physical coordination and physical functioning!

2. the logic of the results of the coordination of the small movements I instructed you to project.

At first the concept of Base is childishly simple. ‘Base’ is just the horizontal distance at the widest measure of the pelvis seen from the front. It becomes much more interesting when you realise that this geometrical standard can be used to guide the movements of simultaneous adjustments of other parts to establish a geometry, i.e. a position, of mechanical advantage. When the exterior of the heels and the exterior of the superior parts of the knees are at the same Base distance, you have an horizontal base for the spine.

Maybe you can reason yourself and accept the new feelings of tension by studying the reasoning leading to the position you assumed consciously.

There is a cause and effect relation between the organisation of the different bones of the lower limbs and the effectiveness of the support of the spine by the pelvis. If the pelvis is habitually tilted as a result of the geometry of the habitual gesture, the lower part of the spine is leaning to one side and shortening on the other. In Alexander’s words, resting and moving with a pelvis tilted to one side represents a ‘position of mechanical disadvantage’ which tends to shorten the spine. There is then an ‘undue tension’ or ‘unbalanced tension’ throughout the whole torso: on this picture, you will see that there is too much tension on the right and too little tension on the left to prevent the torso from falling to the left.

You can draw or reason out two conclusions from these psychophysical conditions:

- releasing the excessive tension or increasing the tension on the flaccid side will not solve the cause of the pelvic imbalance, which is in the geometry of the movements of the different parts of the lower limb,

- of course, the subject has no feeling about this ongoing state of affair, she feels upright when, for an objective observer, she is leaning to the left. She is standing in this way because she feels that she has has much weight on the right and left leg. When I manage to have her create the movements which change her support system to a correct geometry of mechanical advantage, she invariably will say when perfectly centred: “All my weight is on the right now!”.

Knowing how to direct the movements of the feet and knees both for finding rest and for training equal tension in the abductors and adductors tissues of the lower part of the torso (pelvis) should be a primary concern for any system of gestural training. Yet, you must understand that such system must integrate a training of inhibition because as soon as the pupil will coordinate a series of new primary acts to assume and study the “position of mechanical advantage“, he will be confronted with feelings of tension which were not present before and will tend to stimulate him straight away to return to his habitual feeling of rest!

“The minute you change it, the thing that isn’t a strain feels a strain”. (Alexander, F.M.; in Fischer, J.M.O.; Article & Lectures, Mouritz, Teaching Aphorisms, 1995, p. 205)

When we are a child, the organisation in space of the movements of the anatomical structure is not learned by a conscious reasoning process. As a result, most people ignore the simplest geometrical conditions of support and rest between the torso and limbs. Alexander, in his writings, show that he is aware of that fact and even names it “a principle”, “the primary principle in attaining the correct standing position”[1].

I found very strange that (a) Alexander never defined the three terms he used in the “primary principle in attaining the correct standing position” which establishes that the “limbs and torso should be aided and influenced by the force of gravity”, i.e. base, pivot and fulcrum, and (2) that the placement of the feet he advocated (Delsarte’s base n°2 which was supposed to represent weakness for the public in the old acting system) was in violation of the rule he so hastily exposed in his first book. I assumed he may have copied the rule from others without fully understanding what it was about.

I do not intend to explain all three terms here because, in our future lessons, we are going to examine in detail and experiment with procedures each of them and all of them in concert, but for people interested, I just want to state that the two other terms are also to do with the organisation of the series of movements of the ankle and foot in 3D space in order to obtain distant effects (“antagonistic pulls“) at the other end of the anatomical structure.

Returning to the case at hand, it is clear on the film of your lesson that without any instructions (orders of movements) for the knees and heels, these parts, heels and knees tended to move with a [strong] habitual tendency toward the production of unwanted shear forces in the joints when you moved your legs: the heels moved closer together and the knees went apart from each other simultaneously as soon as you fidgeted or started a gesture involving the legs. This is also how (by which coordination of the parts) you assumed your sitting posture on the chair.

This seems to indicate that some muscles connecting the torso and lower limbs are slightly overdoing their part and some others are not playing their part in your habitual way of using the legs in sitting.

I did not tell you to ‘release’ the muscles doing too much or to ‘exercise’ the muscles doing too little. I never talked about them. Rather, I had you work with your mind and command a series of well defined MOVEMENTS, and your work was about subordinating two different motor actions to a geometrical task. I said “use the instruction “I pull the exterior of the knees inward to Base” to instruct the first decision of movement” and “I pull the exterior of the heel outward to Base” to subordinate the motor action to a second geometrical task WHILE you were doing a global gesture (pulling the feet back toward the chair). I knew full well that you had no idea of the number of muscles involved in the tasks and even less of the ones originating in the torso that were doing too much or too little. I said just experiment to see whether you can affect the results of those processes[2]’, see whether you can command a given series of ‘primary acts’ not directly involved in the gesture of moving the legs but which provide a new QUALITY to the gesture.

The second thing that we can learn from watching the video recording of your lesson is that you were able by using the verbal orders of movements, one for the knees and one for the heels simultaneously, to perform one qualitatively new gesture (moving the feet back toward the chair) while consciously coordinating the movements of the feet and knees to base altogether. As far as I can tell, this controlled gesture was totally new to you, you had no previous sensory experience of performing this coordination of movements: the new experience was the “unknown” as far as your sensory experience was concerned.

You did not look too surprised nor elated to achieve this coordination on your fist attempt, yet this is the basis of the psycho-mechanic of the Alexander technique that Alexander called the “means-whereby” principle, the continuous projection of orders of movements.

The “means-whereby” principle calls for the ability “to bring to bear on” a dozen or more objects if necessary, and which implies a number of things, all going on, and converging to a common consequence (continuous projection of orders). (Alexander, F.M.; Constructive conscious control of the individual, Integral Press 1923, reprinted 1955, p. 167, “Projection of Orders”)

It is important to note that the adjective ‘continuous’ is not used in the modern sense of the word, but in a technical way by Alexander when referring to the projection of directions of movements. These orders are not to be projected continuously in the sense of all day, without interruption. It is the projection which must be continuous, i.e. the first order and second and following orders must not be projected sequentially, separately, discontinuously one after the other in time, but simultaneously, “all going on” as in the Classical Latin of the sense of ‘continere’, the etymological root of continuous, ‘to contain’[3].

The common consequence of the direction of the movements of the heels and knees (the four of them) was a different pose of the feet, of the bones of the legs (tibia) and of the bones of the thighs (femur) and it is reasonable to think that the powerful fascias and muscles of the legs which attach to the torso were also used differently from your habit in the reasoned experiment, thereby affecting the torso as a whole in some way as the most powerful muscles attached to the upper and lower leg bones are “muscles of the torso”.

At that moment of the lesson, I made you note that these coordinated movements of the legs had a different impact on the shape of your back, different from your unthinking habitual guidance of the feet and knees when you move your legs in sitting. You looked taller on the chair. I knew you could not feel at that stage this consequence of the conscious coordination of the movements of the feet and knees, but I wanted you to watch the video recording of your lesson to judge whether you could control what I had said afterwards, objectively, by looking at the shape of your torso in the recording before and after you had moved the feet back while directing the movement of the knees and heels altogether. In this way, by reviewing your lesson, you could observe what is not directly apparent, i.e. the relation of cause and effect between a series of movements and the mechanical advantage of the torso. At first, this kind of thinking is not forthcoming without help because modern Alexander technique students are much more attracted by what they feel.

All this experimental procedure was an introduction to the concept of conscious guidance and control, or in more modern terms, an introduction to an action coding system of voluntary gestural coordination of the anatomical structure as a whole.

Converging evidence from many different fields of research suggests that human movements are organized as actions and not reactions [reflexes play no part in postural reactions of subjects without brain damage], that is, they are initiated by a motivated subject, defined by a goal, and guided by information. [emphasis added]. (von Hofsten, Claes; “An action perspective on motor development”, 2004, Trends in cognitive Science, Vol.8 No.6, p. 1).

After this beginning at using a mental benchmark, we started another procedure which was also based on the principle of a conscious mental benchmark to organise a series of movements of different parts of the organism. This time, the conscious benchmark was not “base”, but another concept invented by Delsarte which he called [improperly] “line of oneness”.

I have found absolutely no trace of this idea of spatial ‘benchmark’ or of that particular gauge of “oneness” in Alexander’s writings, yet I was astounded to discover that Alexander (during all his life), and the very first teachers of the Alexander technique (in the 1940’s and 1950 and until Alexander’s death), were all using it in practice. My idea is that Alexander was using this benchmark consciously to organise the movements of the different parts of his torso but that his students were not. Then, when the pedagogy of the technique fell into the hands of the modern Alexander technique teachers, not only the idea, but also the practice became totally lost, to be replaced by the plumb-line concept of lengthening the spine (lengthening the spine on a table top).

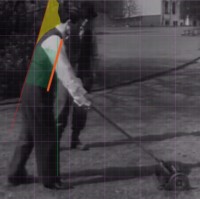

This is a picture taken from a promotion film sponsoring Charles Neil’s work[1] who trained with Alexander. He is demonstrating on film (1953) a capacity to organise all the movements of the different parts of the torso in a manner strictly similar to F.M. Alexander, despite the stimulus of having to move a manual lawnmower on uneven ground. [1] Charles Neil, Film 1953. (called Fitness Exercises (1953) (480p).mp4) seen on YouTube.

You may ask yourself “how does he know that Alexander and a few first generation Teachers were using a visuospatial gauge in the application of his WORKING PRINCIPLE?”. How do I know that the organisation of the ”SERIES OF PRIMARY ACTS which have been thought out as the means whereby a given end can be satisfactorily gained“ is the same thing as the ”harmonic expansion of the torso relatively to a geometrical benchmark?

First, you must take into account that the Working Principle is opposed to another principle which Alexander calls the “habit of end-gaining”. The habit of end-gaining is the manner of the child, the first manner of obtaining an end. The central preconception or idea of end-gaining is that we can trust to what it feels to respond to a verbal stimulus like “lengthen and widen the torso”. On the other end of the cognitive scale, the same end can be obtained by directing a series of movements of the parts reasoned to obtain the end & at the same time obtain certain geometrical relationships between the different parts of the torso which, in the process, realise the orders “let the neck be free, to let the head go forward and up, to let the back lengthen and widen”.

“This habit of ”end-gaining“ is so ingrained that it will create a serious difficulty even where the teaching method is based on the ”means-whereby” principle, and the difficulty can be overcome only if both teacher and pupil at every step in their combined procedure, even the simplest, adhere strictly to the WORKING PRINCIPLE I have set down—namely, that in a series of acts which have been thought out as the means whereby a given end can be satisfactorily gained, the primary act must not be considered as an end in itself, but must be directed and carried out and then continued as the preliminary means of carrying out the secondary act, and so on. (Alexander, F.M.; The Use of the Self_Its Conscious Direction in Relation to Diagnosis, (Third Ed. Centerline Press 1946), p. 42)

I know Alexander is using a visuospatial benchmark to organise all the movements of the parts of the torso at once because in your practical lesson, without knowing anything of the dynamic adjustment of the parts of the torso, you are controlling consciously with rulers that the frontal spots of your torso (which we call Throat spot, Ribs–8th spots, and Iliac spots) are CONTINUOUSLY moved on the same flat vertical plane, a visuospatial benchmark which, as seen from the side, could be seen as line (and if you were a poet, you could call the “line of oneness”).

This is a still picture I took from your lesson, in which you are measuring the result of the movements of the Throat spot, Ribs–8th spots and Iliac spots as seen from the side. The geometrical organisation or ”position of mechanical advantage“ is oddly reminiscent of Alexander’s own performance of his conception of position of mechanical advantage. At least, there is none of the visual gestural defects which Alexander describes abundantly in his books. According to him this ”position” is the solution to the question of due tension in the whole self.

Most people will SEE the photograph of your experiment as a fixed image, but we both know that, during your experiment, you noticed that to reach the benchmark with the three spots —maintain two spots on the benchmark while the third one was moved toward it— you had to continue the movements of the three parts. You could not consider the primary act of aiming the top of the frontal part of the torso on the Benchmark limit Forward, or any other acts, as an end in itself, because due to your past experience, the other parts would not stay in place when any of the other two were moved. This means that, without your conscious continuous series of decisions, it was impossible to approach the benchmark from all sides with the three spots. Just aiming the three spots at the same benchmark imposed that you coordinate the movements as one.

Unbeknownst to you, by using this mental benchmark, you are seen lengthening and widening the torso, sending your head forward and up (without trying to or even thinking about it) and your neck is much freer than in all your habitual gestures[4]. As a result of the concerted movements aiming at a visuospatial benchmark, you are looking exactly like Alexander or his students.

For you produced this gesture on your first attempt, the principle of equal simplicity[5] allows us to conclude with a high degree of probability

- that the structure which governs the production of this given series of movements and the smooth redistribution of muscle pulls is much more closely related to mental spatial form than to muscle scheme, (it is not a progressive training of a somatic control of the muscles by a repetition of correct feelings experiences which brought you to be able to display this organisation of the different parts of the torso) and,

- that Alexander must have learned to command the feat by using the same topological principle, and not by the somatic repetition of trial-and-error approximations of the required form.

In the case of Alexander himself, the learning process must have been different, of course, because he is never seen using any physical ruler to adjust his use of the different movements of the parts of the torso. Nonetheless, to be able to produce this same gesture with a flat back and a “hump” at the top without any ruler, the subject has to direct the movements of the different parts of the torso consciously and to limit the movements of adjustment very cleanly around the unfelt mental benchmark measuring the FRONT of the torso.

Now, without experience at measuring movements with a mental visuospatial Benchmark, it is not possible to obtain the precision displayed by Alexander and a few of his first student teachers. Without benchmark who could tell when to stop the movements of adjustment and prevent overreaching into another extreme: when one is re-adjusting the thoracolumbar curve, how do you know you are not arching in the other direction?

Incidentally, this type of experimental procedure explains why I started thinking that Alexander was taught insider knowledge about the Delsarte action coding system. He boasted he was a Delsarte teacher, but the [no so little] knowledge he had of the gestural system did not seem to come to him by reading the American Delsartist writers. First, he was dead set against the central idea of Delsartism, i.e. relaxation, second he made such strange choice of words [which do not appear in the Delsartist accounts at his time]— and finally this “small detail” of the “lines of unity and line of oneness”, not in his words but clearly in his coordinated actions, all these details made me suppose a possible direct link between Alexander and the original Delsarte teaching. Because the American Delsartists never wrote in any detail about the technical aspects of the gestural system that Delsarte stopped teaching in 1855, I concluded that Alexander must have been taught something of the old action coding system by someone who knew the system directly from the mouth of one of the Delsartes.

Alexander sitting with the frontal plane of the parts of the torso clearly organised with a *series of primary acts* around an imaginary vertical limit which origin is given by the top of his tie.

Coming back to your performance of conscious guidance of a series of movements, there is no doubt that your “back” is back (the thoraco-lumbar spine is flat as a board), that the upper torso is forward with a vertical sternum bone and that you have the “hump” described by Alexander’s friend and pupil George Dudley Best, which makes your head appear very far forward and up relatively to your lower back line.

The benchmark principle here is that three anatomical bony landmarks on the frontal torso have all been simultaneously aimed at the same imaginary flat plane, in opposite directions to each other: some movements had to be directed forward while the next landmark (placed on the next articulated part) had to be directed in the opposite direction. This is the principe of decomposition (disassociating the movements of the different parts) and opposition (opposing the movements of the anatomical landmarks in series) with is the core of the Delsarte Gestural system, the only difference being that here, we have a practical application under our eyes.

And when I compare visually the relativity between the parts, right after your second lesson, you look like Alexander! This is a visual control which you can trust. There is not only the hump and the flat back, but also another orientation of an essential anatomical landmark of the frontal torso is unmistakable: look at Alexander’s tie, how his sternum bone is vertical. At a glance you get an idea of “the correct poise of the upper torso”. This opening of the back of the upper torso is properly impossible for the modern Alexander technique plumb-line idea of a lengthened torso.

How Form affects functioning has disappeared from the modern Alexander technique doctrine. The modern Alexander technique teachers are not teaching conscious guidance, i.e. they are not teaching the series of concerted movements which are the means whereby of the correct use of the torso. All they are interested in is “tension” —something they can feel with touch—and, by a simple stratagem (making something sound true because it is repeated often), they are able to deceive themselves and others to believe that their hands are giving them a reliable information about the activity of the whole structure. As a result, they are not teaching Conscious Control either to apprehend the defects in a human body.

The eye of an artist is needed to apprehend the faults in a painting or in a work of sculpture, and ABOVE ALL, the defects in a human body. (Alexander, F.M., “A protest against certain assumptions”, 1908, in Fisher, J.M.O.; “Articles and Lectures”, Mouritz, p. 115)

When their pupil is left alone after his lesson, he is left with absolutely nothing, except his own feeling of tension to evaluate in which direction he should work. By totally discarding the objective control of the Form obtained after projecting the orders of movements, the pupil is bereft of any knowledge of the motive, guiding and controlling principles of the mechanism he is supposed to guide anew. The pupil can certainly not feel his own body with his own hands to detect the defects which Alexander described from looking into his mirrors.

It is obvious, then, that as soon as the mechanical defects are recognized, all possible means should at once be employed to restore the maximum standard of mechanical functioning. In order to accomplish this, a knowledge of the motive, adjusting, guiding, and controlling principles of the mechanism is needed. (Alexander, F.M.; Constructive Conscious Control of the Individual (Eighth edition, 1946), p. 55)

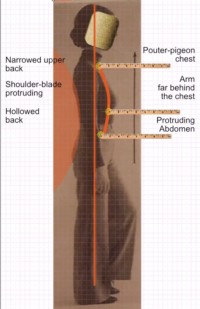

This is an example of the plumb line gesture, the organisation of the head, neck and torso which the modern Alexander technique teachers consider as right. The vertical arrow in the picture indicates that the teacher is “thinking up”.

The plumb line gesture is very different. Here is an example among many of the pictures which can be found on the internet or in books to advertise the modern Alexander technique conception of a lengthening torso (and believe me, I choose a “nice” one). I have added the indications which Alexander gives everywhere in his books about the faults his technique was supposed to eliminate. Here, the defects pointed out by Alexander are proudly presented as achievement of a correct thinking based on the correct “sensations”. Note how the sternum bones is inclined backward at the top and how the convex shape of the frontal part of the torso is related to the protruding middle torso and all the other concerted defects.

I highligthed how the curve at the back is directly associated with the curve at the front because the ribs and the pelvis are attached to the spine at the back. The position of the ribs, the pouter-pigeon chest, the protruding abdomen and the shortened back are all symptoms of the same cause, the incorrect direction of the movements of all the parts of the torso.

It is clear that the modern Alexander technique teacher has no benchmark for the movements of the different parts of the torso, that she does not use the mechanical principle stipulated by Alexander by which a “reverse action on the ribs which tends to straighten the spine”[6].

A little consideration will show that any alteration in the spine must necessarily affect the position and working of the ribs. (Alexander, F.M.; Man’s Supreme Inheritance, (Second Ed. Revised, 1918), p. 202)

2. The question of tension as you feel it

The truth of the matter is that in the old morbid conditions which have brought about the curvature [of the spine] the muscles intended by Nature for the correct working of the parts concerned had been put out of action, and the WHOLE PURPOSE OF THE RE-EDUCATORY METHOD I ADVOCATE IS TO BRING BACK THESE MUSCLES INTO PLAY, not by physical exercises, but by the employment of a position of mechanical advantage and the repetition of the correct inhibiting and guiding mental orders by the pupil. (Alexander, F.M., “Man’s supreme inheritance”, Chaterson Ltd 1910, reprinted 1946, p. 181)

I understand full well that, as a modern Alexander technique former pupil, you would want to discuss your feelings of tension. Yet, I want you to realise that during your lesson, I did not ask you to do any exercise of any type, nor was I interested in your feeling of tension. I asked you to experiment with your cognitive and executive capacity

- to direct precise movements of adjustment of parts of the organism in time and space, giving consent to some pre-planned movements and refusing to give consent to other, automatic movements and,

- to stop the series of simultaneous movements (stop the gesture of adjustment), i.e. stop all the movements of adjustment at the same time to discover what sort of position or relationships between the parts you would have assumed: what we call “a position of mechanical advantage”.

Remember in this regard that I asked you to consciously control that every experiment you were to make —experiments of conscious guidance of a series of concerted movements— should be timed by your own verbal guidance with a definite start (inhibiting any isolated movement before saying “One”) to begin projecting all the movements at the same moment (co-ordination) simultaneously, and with a definite end to stop altogether projecting the movements all together, at the definite moment of saying Three. The whole procedure of saying “One, two, three” and perform the series of movements was supposed to last two seconds. One second between you saying “one, two” and another second saying “two three”. In saying “One, Two, Three”, you were to command the whole procedure. You must also remember that what happened in the hundred of seconds after the counting was also subjected to scrutiny.

When after projecting the movements for the three parts of the torso in sitting and measuring the different ruler-distance to the wall, you said that your neck felt incredibly “Free” while you experienced all sorts of “tensions” in the torso. I was no more interested in the first symptom (neck freedom) than in the second (felt tension in the parts of the torso).

The fact that you felt great tension in the torso tissues indicates that this coordinated gesture was not at all habitual for you. This does not constitute a great surprise. The fact that you felt a great release in the neck also indicates that the position you had just performed for yourself with the different parts of the torso does not belong to your habitual register. I think that you felt the neck because you are influenced by your previous modern Alexander technique lessons —because they insist so much on “feeling the neck”. As your sensory system is adapted to what feels “right” to you, it is clear that you sensory system must have been set on red alert by the performance of the simultaneous movements. When you get some more practice, feelings such as “my neck is incredibly free” will return to their appropriate salience (you will not feel anything) or you will put them in their correct place (you will just discard them as irrelevant).

Now, when I look at you, sitting like this, I see no cause for alarm. The purpose of the re-educatory method proposed by Alexander is to bring back all the tissues in action, not by physical exercises, but the employment of a reasoned position of mechanical advantage and the repetition of the correct inhibiting and guiding orders of movements by the pupil.

I know that the modern Alexander technique teachers all instruct to release tension. It is easy to trace the origin of this misconception or phobia. Alexander himself talks about the “relaxation about unduly rigid parts” as an essential task: if you read and concentrate enough on that sentence without reading further, you could certainly get a few generations of teachers celebrating the cult of doing nothing and probably sacrificing a few innocent children to their fancy.

Therefore it is essential at the outset of re-education to bring about the relaxation of the unduly rigid parts of the muscular mechanisms in order to secure the correct use of the inadequately employed and wrongly co-ordinated parts. Let us take for example the case of a man who habitually stiffens his neck in walking, sitting, or other ordinary acts of life. This is a sign that he is endeavouring to do with the muscles of his neck the work which should be performed by certain other muscles of his body, notably those of the back. Now if he is told to relax those stiffened muscles of the neck and obeys the order, this mere act of relaxation deals only with an effect, and does not quicken his consciousness of the use of the right mechanism which he should use in place of those relaxed. (Alexander, F.M.; Man’s Supreme Inheritance, (Second Ed. Revised, 1918), p. 66)

Indeed, you just have to read slightly further than the first sentence to discover in fact that his technique to eradicate isolated gestural defects is strictly indirect according to the unity principle—as a rule, one should not try to release a symptom of tension felt with the habitual sensory appreciation by a direct act of release. The establishment of due tension should happen in the process of guiding a concerted use of the whole by studying how to assume a position of mechanical advantage.

Alexander should have explained from the start that releasing one part, getting rid of the symptom of tension is end-gaining because the use of the self is CONCERTED, that there is not one movement which can happen without the whole structure reacting in the habitual way, so trying to make a nice isolated change is not helping but making the establishment of a correct coordination more complex.

“It is in the nature of unity that any change in a part means a change in the whole, and the parts of the human organism are knit so closely into a unity that any attempt to make a fundamental change in the working of a part is bound to alter the use and adjustment of the whole. This means that where the concerted use of the mechanisms of the organism is faulty, any attempt to eradicate a defect otherwise than by changing and improving this faulty concerted use is bound to throw out the balance somewhere else. (Alexander, F.M.; The Use of the Self_Its Conscious Direction in Relation to Diagnosis, (Third Ed. Centerline Press 1946), p. 30)

Alexander should have told his students that the pupil would need to inhibit his desire to release at the first sign of serious symptoms of tension. There should have been quotes everywhere in his books about the real conception of inhibition, i.e. refusing to do an isolated act of relaxation which does not take into account the direction of all the movements of the parts.

It is an individual misconception, error, and delusion to attempt to gain benefit by relaxation in consequence of the recognition of undue tension of the muscular mechanisms, not only in physical acts, but also during the attempt to rest by sitting in a chair, lying on a bed or couch, etc. (Alexander, F.M., “Man’s supreme inheritance”, Chaterson Ltd 1910, reprinted 1946, p. 156)

All these reasonings explain why I cannot teach the semi-supine rest cure (and because the table top establishes a totally wrong benchmark for the coordination of the different parts of the torso).

Alexander again should have told his students that he was looking to establish due tension in the whole organism, and not an absence of felt tension.

My next instance—namely, “relaxation”—is even less efficient. The usual procedure is to instruct the pupil, who is either sitting or lying on the floor, to relax, or to do what he or she understands by relaxing. The result is invariably collapse. For relaxation really means a DUE TENSION of the parts of the muscular system intended by nature to be constantly more or less tensed, together with a relaxation of those parts intended by nature to be more or less relaxed, a condition which is readily secured in practice by adopting what I have called in my other writings the POSITION OF MECHANICAL ADVANTAGE. From an incorrect understanding of the proper condition natural to the various muscles, the theory of relaxation, like that of the REST CURE, makes a wrong assumption, and if either system is persisted in, there must inevitably follow a general lowering of vitality which will be felt the moment regular duties are taken up again, and which will soon bring about the return of the old troubles in an exaggerated form.

(Alexander, F.M., “Man’s supreme inheritance”, Chaterson Ltd 1910, reprinted 1946, p. 15)

Finally, Alexander should have said to his students that his technique of conscious guidance and control could only lead his pupils to new fruitful experiments if they accepted to FEEL WRONG and were prepared to feel real discomfort. Obviously, if the habits of use of a pupil is to slump in sitting, and if he has done that dynamic gesture for years, you must imagine that many tissues, fascias and muscles which have been put out of action for LONG PERIODS will not start working as new from the start. They will feel sore and difficult to command: the whole sensory outlook of the person, his gratifying protocol, are going to be turned upside down if he engages in a process of reeducation, readjustment and coordination.

To act successfully along new lines of thought means (even after the best “means-whereby” have been selected) the carrying out of a decision by an unfamiliar use of the self against the impulse to carry it out by the habitual use that feels right, that is, not only in the face of our mental conception of HOW that decision should be carried out, but also IN THE FACE OF REAL DISCOMFORT AND “FEELING WRONG” IN CARRYING IT OUT. For this reason the person who has hitherto depended in all his “doing” upon an instinctive (automatic) use of himself finds it difficult to adhere to a decision to employ procedures which involve a guidance and control in the use of himself which is not in line with any previous experience either in thought or in action. The new “means-whereby” are unfamiliar, and any attempt on his part to carry them out will be associated with experiences which feel wrong, so that in order to be right in carrying them out, he will have to “do” what he feels wrong—obviously an experience which will be entirely new to him”. (Alexander, F.M.; The universal constant in living, Chaterson L.t.d., 1942, third edition 1947, p. 98)

The fact that you are worried by feelings of tension considered as “serious symptoms” which call for immediate eradication and future prevention should have been anticipated by Alexander.

The attempt to gain benefit by relaxation in consequence of the recognition of undue tension of the muscular mechanisms, not only in physical acts, but also during the attempt to rest by sitting in a chair, lying on a bed or couch, etc. The detection by the subject of SYMPTOMS WHICH ARE ALWAYS CONSIDERED SERIOUS and call for immediate eradication and future prevention. The original conception in this connexion is influenced by warped and incorrect subconscious experiences, and consequently a narrow and perverted view is taken of the conditions present. The one brain-track method is in operation and the modus operandi adopted by the subject is therefore deduced from false premises. Symptoms are considered causes, and furthermore the chief aim of the subject in practical procedure is the attainment of the ‘end’ desired, not the due and proper considered analysis of the ‘means whereby’ which will secure that ‘end.’ (Alexander, F.M.; Man’s supreme inheritance, (Second Ed. Revised, 1918), p. 178)

As you must have noticed, during your first two lessons, it was never question of what sort of tension you were feeling. I expected you to feel wrong after working actively for two seconds, and especially AFTER the TWO SECONDS because the procedure explicitly asked you to inhibit all movements after the count of three.

At one moment, I had you note how difficult it was for you to inhibit the series of habitual movements you do to assume your habitual posture in sitting once you had performed the means of the position of mechanical advantage. What is interesting in this event is that you felt acutely the new movements you had to do but, on the opposite, when you reverted to your habitual position by a series of unreasoned movements just after the count of three, you did not feel YOU WERE DOING THESE wrong MOVEMENTS, and at first, it was difficult for you to believe that you had DONE the wrong series again.

A lot of the discomfort we experience comes from the somatic craving to go back to the habitual use of the torso. It was clear at that moment that your sensory appreciation was commanding your behavior, that you were not free to stay in the new position of mechanical advantage even if you wanted to, that you needed to go back spontaneously to your habitual shortened gesture. I am quite confident to say that your sensory appreciation has usurped the role of your reason because you had not realised that you had been videoed DOING all the movements to go back to your old posture, because it happened so fast below your awareness.

I know full well that the modern Alexander technique teacher have made their business to encourage people to pander to their sensations and think about what they feel. Yet, you did not feel anything when repeating your habit. This is something to reason about which is much more interesting than hash over felt tension, or at least we should take the large view and find the reason why we feel so much and so little at the same time, always missing the global picture. I can only ask you to read what Alexander is saying and make your own mind about it.

There is considerable confusion on the part of the pupil when he attempts to obey directions to relax some part of the organism. In ordinary teaching, pupils and teachers are quite convinced that if some part of the organism is too tense, they can relax it—that is, do the relaxing by direct means. This is a delusion on their part, but it is difficult to convince them of it. In the first place, if they do chance to get rid of the specific tension it will be by a partial collapse of the parts concerned, or of other parts, possibly even by a general collapse of the whole organism. In the second place, it is obvious that if some part of the organism is unduly tensed, it is because the pupil is attempting to do with it the work of some other part or parts, often work for which it is quite unsuited. (Alexander, F.M., “Man’s supreme inheritance”, Chaterson Ltd 1910, reprinted 1946, p. 109)

So in conclusion, is there’s the possibility of “over doing it” some times and end up with more muscle tensions than before?

Well in projecting directions for a series of movements which lasts two seconds, it is IMPOSSIBLE.

And it is not so because two seconds is too short a time (at first you will see that the instinctive tendency is to project the movements for more than two seconds and to experience difficulty in breaking the habit of going on unthinkingly), but because the new directions of movements are designed to ensure a due tension of the tissular systems (fascias and muscles) throughout the whole torso. The fact that we are using a mental benchmark to limit all the movements of the series of adjustment makes sure that it is impossible to end up with more tensions unbalance than before directing the system consciously. Now, a completely different question is whether you will feel that you are not doing too much? To that one, I must also answer by the negative. Every single time, if you dare step out of your comfort zone, you will again get the distinct impression that you are bringing tension in parts which have been put out of play. It is like the different skins of a very very big onion.

The most likely possibility is that you will “underdo it” most of the times and end up with an incorrect balance of tension, i.e. your habitual conditions of use.

So I am not the least worried in this aspect. I am all interested rather in defining the correct directions, geometrical directions of the pull we want the structure to produce for you. To produce forces and work for you at no cost, the elastic systems of the torso must be strained (to strain means to pull or push against a structure with mechanical loading to obtain a geometrical deformation most of the time in the direction of length), to protect your bones and cartilages, strain must also be applied in the correct direction.

All this loading and proper strain is not something we want your efforts, active muscles forces to produce The orders of movements are not orders to tell yourself to do this or that in order to do the antagonistic pulls yourself. The technique is much more subtle than that. You are ordering movements for two seconds to organise the geometry which will create the appropriate loading ALL THE TIME, as long as you can inhibit coming back to your old feeling of rest. The loading will be coming from the geometrical system of the bony levers of the anatomical structure, i.e. the loading will be coming from what Alexander called “positions of mechanical advantage”. The directions of movements, the orders we use are just to organise the geometry of the structure. There is not need of doing anything when the position of mechanical advantage is organised in the spatial field: this is the point, once you have done your best with the movements of adjustments all you need is to study the position of mechanical advantage and allow yourself to feel wrong.

Let’s conclude this long answer by a last question: Could it be possible that you allow the position of mechanical advantage to stay for too long? Again, I must answer by the negative: No, you cannot do that because the hold your sensory appreciation has on your guidance is so strong that you cannot stop your subconscious easing movements for more than twenty seconds or so even if you try your best. It will take time…

- “From what I have now said, it will be quite evident that the primary principle involved in attaining a correct standing position is the placing of the feet in that position which will ensure their greatest effect as BASE, PIVOT, and FULCRUM, and thereby throw the limbs and trunk into that pose in which they may be correctly influenced and aided by the force of gravity (Alexander, F.M.; Man’s Supreme Inheritance, (Second Ed. Revised, 1918), p. 188). ↩

- “If you do anything to affect the processes, you must do something that will affect the results of those processes. ( Fischer, J.M.O.; Article & Lectures, Mouritz, Teaching Aphorisms, 1995, p.Alexander, F.M.; p. 202) ↩

- Again, it is slightly bizarre that a more or less uncultivated Tasmanian would use an expression which does not belong to the English denotation of the word but rather seems directly taken from the jargon of the French Académie Française. ↩

- This is a conjecture based on observed facts and not a feeling. ↩

- Bernstein, N.A., in Coordination & Regulation, 1967, p. 54 explains how a complex movement cannot be the result of a somatic training using his “principle of equal simplicity”. ↩

- “On the other hand, we see that by increasing the thoracic capacity and so increasing the distance between the ends of these ribs, we are applying a mechanical principle which by a reverse action tends to straighten the spine”. (Alexander, F.M.; Man’s Supreme Inheritance, (Second Ed. Revised, 1918), p. 204) ↩

Leave A Comment