1. Working to principle when faced with the unusual and the unexpected

This paper aims to show how “conscious control“, that is, control by guiding our mind with a series of verbal & rational instructions makes it possible to meet the requirement of a new task or, as Alexander explains, to meet the requirement of a new environment.

In this workshop, the “physical task” of the procedure presented is just the backdrop of the fundamental reeducation of the mind that the initial Alexander technique has to offer. Readjusting the whole anatomical structure is just a means [to develop conscious guidance and discipline] and not the end.

1.0. Overview

During the “Alexander Technique International” Congress in Ennis, I was allowed by the organisers to present two (short1) workshops despite the fact that I have never been a member of this Organisation of teachers.2

This short text is a general inspection of the introduction of the second workshop I gave on the subject of the relation between “conscious guidance and control” on one side and “conception” on the other.

The reason why I present this short paper is that I want to thank all the Irish, European and American teachers who made my stay in Ireland so easy and studious, as well as open minded and friendly. They all made me feel “at home” during my two weeks stay in Ireland, so that I could thrive in the spirit of inquiry which motivated these people to evaluate something beyond their habitual understanding of the Alexander technique theory and practice. You could consider that this text is an after-sales service for people who have attended one of my workshops either before or during the ATI conference.

Many of those who organised or participated in the two workshops I gave in the week prior to the Alexander Technique international Congress in Galway and Ennis could not attend the ATI Congress for various reasons, and I hope that this text will help them criticise the methodology3 I am proposing with yet more accuracy. I do not know how to give them a gift in return for their openness and patience, but by writing yet another analysis of my way of understanding the work.

1.0.1. Contents

Working to Principle when faced with the unusual and the unexpected

[workshop Resume, ATI 2019 Ennis]

1. Working to principle

1.2. Introducing the work to a layperson

2.1. Analysis of the mindfulness embodied plan

2.2. Analysis of the mindful gesture

2.3. Starting to experiment with reasoned acts

2.4. Establishing the connexion between cause and effect

2.5. What movement are you seen doing first?

3. A reasoned analysis on a reasoned plan

3.1.1. Realising the undeveloped condition of conscious guidance

3.1.2. A word of caution regarding the word position

3.3.1. Linking the movements of the arm with the movements of the parts of the torso

3.3.2. Disassociating the movement of the frontal plane of the torso from the movements of the limbs

3.3.3. Acting under the guiding principles of reasoned and conscious control

3.3.4. Linking the movements of arms and legs with that of the torso is the recipe for poise

1.1 Introducing the work to a layperson

Frequently, when sitting in a plane or at a social meeting, I am asked what it is I do for a living. Most often I do not answer that I am an Alexander technique teacher. I just say that I teach discipline, that is “self-discipline”, a process to train the capacities (a) to understand some principles, to reason some rules and rehearse precise instructions, and foremost (b) to stick to the decision to put them into practical procedures.

When explaining the genesis of bad habits, Alexander saw lack of discipline, i.e. the dangerous habit of not hearing any instructions4 as closely linked with the dependence on the feeling sense5 for guidance in the affairs of life. As the way in which the two things are connected together may not appear easy to see or understand by most modern Alexander teachers I have prepared this workshop.

The practical application in this second workshop [of the ATI conference 2019] was to examine the question of “discipline”, that is the problem of conscious guidance and control in the gesture of leaning forward and back with the torso.

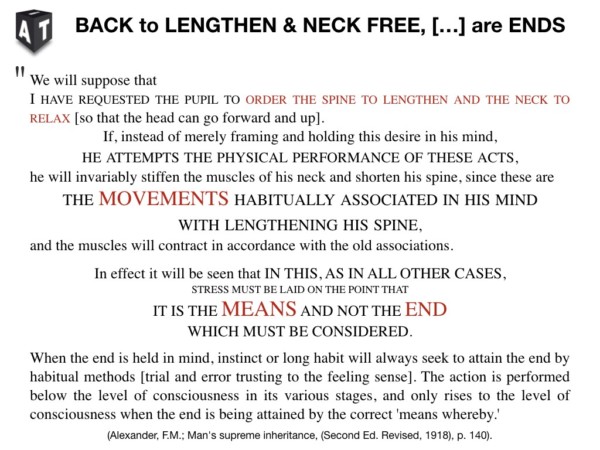

Alexander is taunting us with his statement that none of us want the discipline, but to overcome his stimulating sally (rebuttal), we need to go back to his books to translate his principles, rules and orders into something we can comprehend.

To present (a) the concepts which are central to Alexander theories and (b) some of the aspects of his methods designed to experiment the practical consequences of these theories, I improvised an introduction to convey how discipline, principles, rules and orders could be made intelligible to modern Alexander technique teachers. It is this introduction I gave and which clarifies the bridge between theory and practice that I am going to discuss here in this paper.

In my own progressive immersion in the modern Alexander technique twenty five years ago, all the modern Alexander technique teachers who worked on me cared about was to convey a sensory experience brought about by their knowing touch when they were guiding my movements.

Firstly, they did not tell me anything about the discipline in which the pupil was supposed to train to implement the technique Mr. Alexander had invented to change by his own means his wrong habits of coordination in his own activities: these respected teachers all thought that feeling the experience provided by the touch-teacher should be sufficient for the pupil to grasp what is meant by “working to principle in dealing with new and unfamiliar situations6“. They dismissed the fact that Alexander himself never needed to receive a touch-lesson in his entire life to develop his capacity of conscious guidance and control which led to the eradication of the psycho-mechanical defects he had cultivated.

Secondly, they did not care to explain how the lesson they were giving me were related to the books Alexander had written and to the theories (principles) he had patiently constructed all his life. The more they persevered in this way, the more I started to get the distinct impression that despite the fact that they sometimes repeated Alexander’s aphorism “it’s all in the books7“, they in actual fact did not care at all to explain to me the basic relation between the theories that were exposed in the books and their practice supposedly based on these theories. I did not want to reproduce that same pattern, so at the very start of the workshop and in order to tackle this very point, I asked all the participants to tell me whether they wanted a workshop on the theory OR on the practice of the technique involved in changing habits regarding the gesture of leaning forward or back. The overwhelming majority [20 to 1] of the modern Alexander technique teachers voted for practice and against theory.

I said that I expected them to react in this way, i.e. one way or another, but that I nevertheless wanted to get across a third way, that of bridging the gap between theory and practice in one’s own method to deal with defects and problems. I said that I believed that the third way was closer to Alexander’s written legacy.

Most Moderns separate the somatic, embodied cognition of the working organism from a mental, supposedly isolated and cold reasoning mind. In my eyes, the Moderns thrive on the mental/physical divide, and boast to whoever wants to listen that they have discovered a new somatic mindfulness which requires no theory but just a simple act of renouncement of reasoning. Alexander on the contrary thought from the start to the end that he had invented a technique for building bridges between the two different realms. Unfortunately, the 21 answers pro or against just showed that his idea regarding the carrying out of a reasoned plan or theory in practice had not survived his death.

The question is therefore to know whether we can ask our pupils [and ourselves as our first “pupil”] to engage by themselves in a circuitous path [an indirect route of discipline] to change their habits, that is to say, a re-education path in which they themselves have to reconsider both their conceptions, their actions and the link between them through a discipline training.

This will explain why I did not attempt to make the participant “have a striking sensory experience” (of lightness and freedom) but, instead, to reason out what could be the meaning of Alexander’s concept of “working to principle in applying the technique” of eradication of psychophysical defects. Working to principle is just another name for Discipline, i.e. training oneself to act in accordance to the means-whereby principle.

2. The human Factor: lack of reason in action

After an industrial disaster, a financial crisis or a plane crash it is often the case that the human factor known as lack of reason in action represented the straw that did break the camel’s back. The growing incapacity of children and adults to “apply their mind” on structured mental work and their difficulty in remembering the shortest list of instructions, let alone to subordinate their actions to them in spite of adverse conditions (any situation which elicits strong feelings or the slightest out of the ordinary sensation can now be seen as an adverse condition), is another symptom of the modern cultivation of guidance through sensory appreciation and the quest for good emotions and feeling tones.

Did F.M. Alexander really say that we must relinquish all education methods which tend to cultivate guidance by sensory appreciation?

This is not the kind of message that you can easily communicate in a congress of a somatic technique. Teaching “discipline” sounds horribly old-fashioned to the point of having no echo in the modern world. This is rather sad because a training in such a technique would easily attract many people who more or less consciously realise the need they have to come back into communication with their reason, not only in the social sphere, but in their dealings with themselves.

2.1. Analysis of the mindfulness, embodied plan

To get my point across, I explained that I had a practical procedure designed in order to make things clear for the audience and I requested a teacher to give her/his consent to participate in an experiment whose main points were

- to test whether discipline, i.e. conscious guidance and control, could be useful in the conduct of life and, if this was the case,

- to show how it could be taught.

A young modern Alexander technique teacher freshly qualified accepted to lend us his mind and body to serve as a remote Indian island pig for the experiments. In contrast with the small animal which was used in researches in past ages, the courageous teacher was extremely tall and well built and the chair which was part of the experiment looked like a toy chair, way too small for him.

We were about to see that, despite the appearances, a small tool can elicit quite a large amount of anxiety when we are immersed in the feeling sense, that is, when we are out of communication with our reasoning.

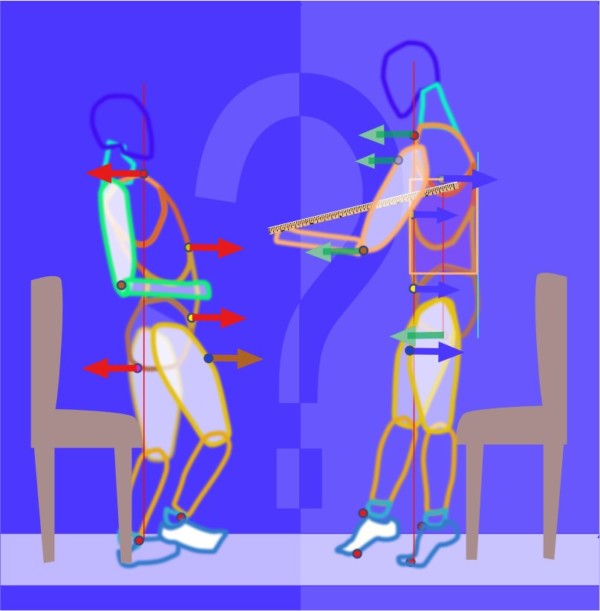

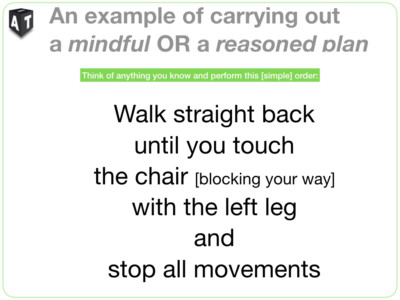

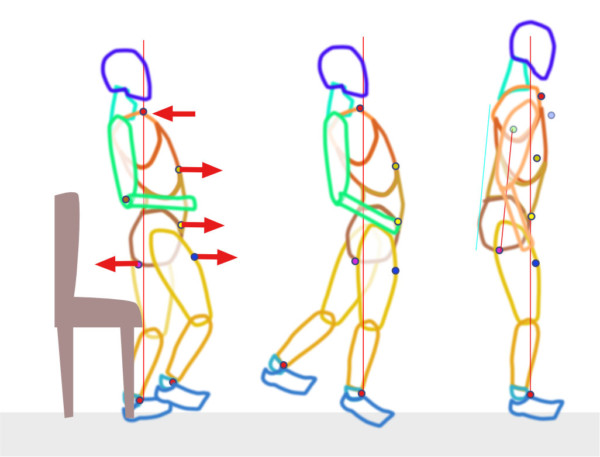

The activity appropriate to the analysis of the problems involved in carrying out an activity without reasoned plan (mindfulness) OR with a reasoned mental plan (means whereby principle) was spelled out as “Walk straight back until you touch a chair [blocking your way] with the left leg, and at that moment stop all movements”.

When you start analysing this procedure in detail, you will realise that the order indicated on the slide involves two different commands which only specify the start and end of this procedure: there is one general order at the start and a general order at the end of the procedure, while the middle, the HOW of the procedure is left blank.

The procedure involves the experiment of walking backward in space toward a chair/obstacle which is not in the field of vision of the operator. The chair stands behind the operator, somewhere in space, as an obstacle.

The first verbal order is to start walking backward from a starting line [represented by a small and flat ruler of wood placed on the floor] on a rectilinear trajectory. The second order is to stop all movements after connecting the left knee with a chair set in the middle of the room and blocking the path of the subject walking backward.

No reasoned means-whereby directions are indicated at first for the HOW to fulfil the task so that the subject cannot consciously command the HOW of the task: therefore the first attempt at the activity will be a carrying out of mindful, embodied plan of action and not a reasoned means-whereby plan. I suspected that a person trained in the modern Alexander technique pedagogy, i.e. trained to feel what is right, would not be able to consciously command the concerted movements of the parts of the anatomical structure. It was a gamble, but I repeatedly advised the teacher to use anything he had learned in this mindfulness and somatic training in order to perform this task (“connect with the space around you and behind you”, “direct and feel the release in yourself”, “let the neck be free to let the head go forward and up and …”, etc).

Before the first attempt, I asked the tall teacher to stand behind the starting line FACING the chair indicating that it was the target for the left-knee when he would be moving toward it walking backward. I told the teacher that he could evaluate the distance between the starting line and the front of the seat of the chair with his eyes if he so wanted, but I said that the most important thing was to calculate a straight line between the two—starting line and chair/obstacle— to guide his walking.

I had made sure that the starting line and the front of the chair were exactly ninety degrees to the walls on each side of the chair so that the trajectory would be easy to calculate: as long as the course of the walk was parallel to the walls the subject was sure to connect with the front of the chair by the shortest route. Then I asked the teacher to turn his back to the chair and I instructed him to memorise two rules: “I will say ONE aloud” when I project the decision to start to walk backward” and “I will say THREE aloud when I have connected the left knee to the chair at the end of the walk”.

These rules were designed to make sure that the teacher was in control of the start and end of the activity and that nobody, such as myself acting as experimenter or the audience, would make the decisions for him. The capacity to follow the rules and to say the words {one, three} appropriately would also indicate to the audience whether the teacher was sufficiently poised mentally to speak the correct number at the right time according to the rules stipulated in advance. I asked him whether he understood correctly what he had to say to comply with the two rules. He said that everything was clear.

I then instructed the audience to watch the teacher carrying out the plan and to note the effectiveness of the first method of procedure.

2.2. Analysis of the mindful gesture

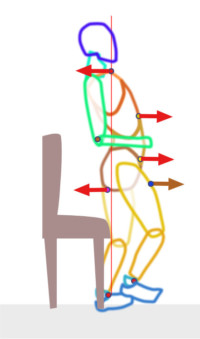

Everybody waited for the experiment to begin and finally saw the young teacher start to walk backward just before saying “one”, with the knees bent low, an arched back, a pouter pigeon chest, and the upper torso pulled very far back.

Many will argue that initiating walking backward and speaking at the same time is a difficult task, but one does not train in the discipline required to react appropriately when there is no difficulty whatsoever. The initial difficulty of using instructions and movements together should not hide the fact that, with training, every student can start using verbal instructions to time exactly the start and the end of a series of movements of adjustment. I gave the example of an orchestra where a musician would start before the timely order given by the conductor: the musician would have to find some help to act in accordance with instructions. Any specialist of concerted movements will tell you that “time is of the essence” of coordination.

Speaking of time, the speed of walk was slow and, upon arriving in the vicinity of the chair, it was perfectly visible that the teacher was slowing down even more, nearly to a stop, to the point that, before connecting with the chair, the teacher after making so many little steps could not believe that the chair had stayed on the floor behind him. Before making the contact with the chair with the back of the leg as commanded, he simply turned around and stopped to see where the chair was.

During his walk, everybody could hear a TWO being said—this was not requested by rule but an automatic verbal sequence— but they discovered that he had stopped all movements without saying THREE, firstly because he had not connected with the chair but secondly, and more importantly, because he had lost track of the plan which was explained to him one minute earlier. His feelings had told him that the chair should be there and, as it was not to be felt yet, he “had to” turn around before completing the procedure. This was another piece of evidence that he was guiding himself with feelings. I could say that his guidance by the feeling sense in the activity made him stray from his original plan of employing the precise instructions of the procedure and he could not stick to his decision8 at the psychological moment.

Lack of discipline tends to insinuate itself into the smallest cracks of “trivial” activity.

We then saw that the whole gesture of stopping-turning around was performed with the very shortening of the stature that walking backward in the manner indicated provoked, making the collapse of the torso and the other psycho-mechanical defects even more striking. The unusual activity had prompted —had made him react with— a marked shortening of the stature and, at the end of the procedure, the young teacher did not think of “straightening his stature” as if he did not realise what had happened.

In walking backward with mindful guidance, the reasoned plan “making one step back after the other” leads to a shortening of the torso consecutive to a wrong series of movements of the parts and we can only note a resulting lack of equilibrium and lack of confidence. Hitting on the chair too fast in these conditions of lack of poise represent a real risk of falling down backward.

Had the young operator moved on his trajectory two seconds more [he was moving backward so slowly at this point] he would have connected the RIGHT knee to the chair. In actual fact, he stopped all movements too early and failed to implement the procedure. Then, it became clear to him that he had not followed a straight path but had strayed to the left. He could not have connected with the left leg because he had moved involuntarily to his left, so much so that the left leg was not directed at the chair anymore.

I asked the teacher to note the discrepancy between the END indicated by the instructions he had received and the result of his actual practice. I quickly said that we were not interested in the result, but that we wanted to see whether he could take advantage of knowing that he had stopped too early and strayed to the left to change in advance his next attempt. He noted that he had not connected with the chair with the left leg, that his walk had stopped short, that he had not said “three” because his mind was racing elsewhere and that he had clearly gone to the left. He decided that he would have another go.

As I have said, he did not appear to have noticed

- the harmful manner with which he moved the different parts of the torso and the limbs during his attempt, and,

- the fact that his peculiar way of moving the limbs and torso were clearly responsible for his tendency to walk diagonally instead of straight.

- that the “physical disequilibrium” in the use of the different parts of his anatomical structure was directly related to his incapacity to stick to the decisions of following the rules in practice.

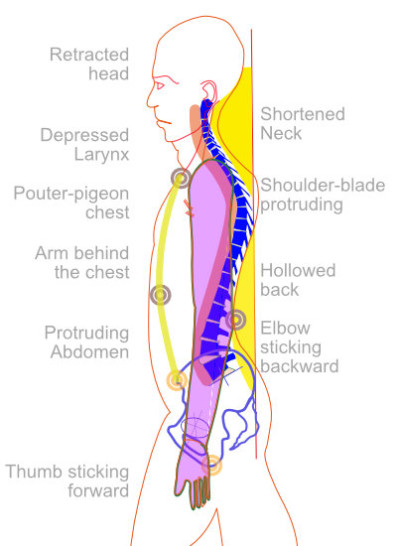

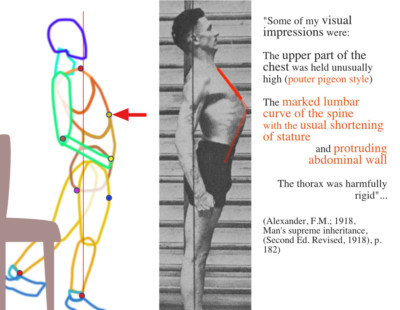

The operator’s movements in walking backward reveal all the “visual impressions” recorded by F.M. Alexander and described as “mechanical defects”.

Walking backward produced a series of visual symptoms of the lack of conscious guidance of the preliminary movements of the different parts of the torso which Alexander listed in his books: “the apprehensive mental condition in practical affairs, the upper part of the front of the chest held unusually high (S-bent pouter-pigeon style), the marked lumbar curve of the spine, the pressure of the under part of the jaw and the lower part of the back of the head, etc. (Alexander, F.M.; Man’s Supreme Inheritance, (Second Ed. Revised, 1918), p. 178)

The second attempt at walking backward toward the chair was a curious remake of the first. His reaction to the task of walking backward was an exact repetition of his first attempt, despite the fact that he had now foreknowledge from the benefit of hindsight with regard to his first practice. Again he shortened his stature (his torso) in the same convex arc as before, he strayed involuntarily in the same way to the left, he slowed down radically in the vicinity of the chair, etc. Yet, this time he was able to walk further back than previously [without stopping the procedure] and he did connect with the chair with the RIGHT knee in saying “three”. Even when connecting with the chair at near zero speed, everybody saw that he nearly lost his balance.

After recovering from the disequilibrium which resulted from his light collision with the chair, he mentioned (a) that he had started to walk back this time with the opposite foot (compared with his previous attempt) because he hoped that this would help him to make the connection with the foot mentioned in my orders, (as during the previous attempt he had missed to connect with the left leg) but that he still arrived against the chair with the right back of the knee. In this way, he pointed out that he was reasoning not about the means but only about the end to be gained.

This time at least, he had been courageous enough—considering the dis-equilibrium of his walk backward— to touch the chair, again with the back of the right leg and stopping short before connecting with the left leg as ordered. Had he made one more step after touching the chair with the right, he would have touched the chair with the left knee, and could have said “three” appropriately, i.e. as requested by the instruction given to him, but it became apparent (1) that he stopped for lack of equilibrium and (2) that he had understood the instruction in his own way. For him, “until you touch the chair with the left leg” could only mean “touch the chair with the left leg FIRST”. This should not disguise the fact that his feeling prevented him to stick to his decision to implement the order contained in the order defining the task.

2.3. Starting to experiment with reasoned acts

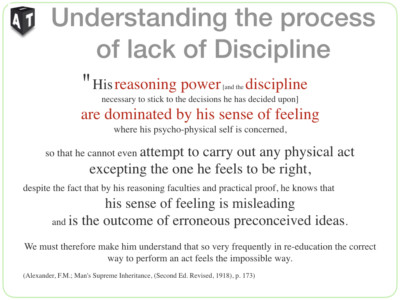

I fully understand that “knowledge concerned with sensory experiences cannot be conveyed by the spoken word, so that it means to the recipient what it means to the person who is trying to convey it9“, but the main question in the young man’s reaction to the unusual task was clearly not “how he should have felt” [finding in his past experiences an embodied solution to the present and slightly unusual task], but how he could have reasoned with the [conceptual] elements at his disposal to guide his performance. The fact is, his reasoning power was dominated by his sense of feeling and, for this very reason, he could not adapt himself at once in the face of the unaccustomed.

Nothing, but the subjective habit10, i.e. the cultivated habit to feel instead of reasoning, the old manner of working by means of one mechanical unintelligent operation, really prevented him

- from analysing the words given to him to start and finish the activity and,

- from analysing the reasonable means whereby a certain end can be achieved11.

He had not analysed the instructions given to him nor the movements of all the parts of the system which could provide mechanical advantage in walking backward, because he had been trained in a scheme in which instructions are secondary to the embodied feeling experience they are supposed to be associated with. This is my main dissent with the dominant and coercive somatic ideology of the modern Alexander technique.

It was rather obvious that he had not been trained to listen to, memorise and analyse series of instructions so as to form a reliable plan of actions: in Alexander’s words, he did not possess the psycho-physical equipment necessary for the ready assimilation of the teacher’s instructions12. Here we see the biggest difference between conscious guidance and control and somatic training: the latter (somatic or embodied cognition training) is based on the idea of associating a verbal instruction with a supposedly correct feeling provided by a touch-teacher while the former requires the building of the DISCIPLINE of memorising, analysing, understanding and learning to act in accordance with the new instructions13 irrespective of the feeling arising from the activity indicated by the procedure.

One thing is certain, the activity was making him feel a lot of anxiety and worry about the result, but in contrast, it is astounding how little he “felt” of the different movements he was making with the different parts of this torso when he was moving his feet.

From that observation, I planned to help him describe with words the synchronised movements he had not felt he was doing so that he could start a reasoned analysis on a reasoned plan. A description with words is essential to reason the equilibrium of an articulated structure in an act of locomotion, and in this way, find a way to stick to the decision (the order to touch the chair with the left leg) no matter what is felt in the process. This is the only way to start experimenting with reasoned acts and not merely imitative acts (acts which are attempts at imitating the feeling received during a touch-lesson).

As I said, he could have analysed the instruction and noted that the adjective “first” was not part of the clause “walk straight back until you touch the chair”; had he been trained to take instructions seriously and to analyse them strictly, he would have found that he could dismiss the problem of which leg should touch the chair first and simply not stop his movements until he had touched the chair with the left leg as ordered (even when he connected with the chair with the right leg first). I must say that I said nothing to dissipate the misunderstanding, leaving the interpretation of the orders entirely to him.

After the first two attempts, I started to ask him some questions. The dialogue was aimed at reasoning (a) an analysis of the movements of the parts which had led to his lack of confidence and (b) some new orders regarding the movements of the parts of his organism which could help him direct his new deliberate decisions of movements rationally14 instead of with his feelings [what Alexander calls directing his will with rational orders]. Exactly like Alexander before him,15 the pupil must learn to “manipulate16” his own mechanism of the torso with a reasoned series of decisions of movements, that is, he must learn in the first place to manipulate the concerted movements of the parts mentally, i.e. by employing his reasoning processes, to represent and model the effects of the movements of the different parts in space, before attempting to enter into action and conduct [self-manipulate] the simultaneous, deliberate and concerted readjustments of the parts.

Deliberated conduct is the result of a dialogue with oneself, but it is the teacher’s role to initiate that particular dialogue which questions our movements of the parts and create the conditions for the student to have himself/herself accustomed to this kind of process of analysis and practical experiment so they can start solving problems and eradicating mechanical defects on their own.

On this subject, there is no way a teacher could build the bridge between theory and practice for his pupil, because what the pupil will need is the discipline to build by himself as many bridges are required during his journey toward an understanding of the true use of the muscular mechanism.17

Any new deliberated series of actions can only appear if practice is subordinated to a plan, i.e. a theory, and this plan will vary with each pupil18 and with each stage of the development19 of a pupil. It is therefore obvious that the student must learn to analyse the conditions present and reason out for himself new series of instructions of movements at each stage of the process of eradication of defects. A fixed series of instructions can in no way be helpful for the student to start a process of inquiry into the eradication of his psycho-mechanical defects.

2.5. What movement are you seen doing first?

I asked him whether he knew which part of his organism he was seen moving first toward the chair-target. To help him understand what I meant, I told him that everybody had seen him move exactly as if he had given himself an ORDER to move one part of the structure before all others. I wondered whether this first ORDER of movement was reasoned or not.

He thought about it a few seconds and then he said that it must be the foot. We agreed that he was, according to his own words, ordering himself to “step back” with the foot. The ORDER was not an order “to the foot”, but an order to-move-the-foot and to move it first before ordering any other movement of the parts of his anatomical structure. The audience testified that he was seen planning and managing his equilibrium to move his foot before his torso in space at each new step. Everybody had seen that his foot landed quite far back relatively to his upper body [upper torso] as long as he was still at a distance from the chair/obstacle. The nearer the obstacle he was, the shorter his steps were becoming.

I noted in passing that he had transformed “walking straight back” (the activity I had proposed and described as “walking straight back”) into his own conception of “stepping back” which involved a placing of the foot backward relatively to the torso.

He said: “Of course, I must step back with the foot first if I want to walk backward”!

To show him how central this movement of one part was to his conception of walking backward, I asked him whether it was possible to imagine any other meaning to the expression “stepping back”. Could he reason out another conception for the act of stepping back, especially one which was not made of the first movement of the foot backward? He was startled by this new question. “Of course to step back you have to put the foot back first“! His conception of the act started to appear in the background of his performance as a rigid idea which brooked little dissent.20

He did not perform the action as an animal would, by instinct: he had a non-explicit pre-plan strategy to guide his movements and he believed that leading with the foot first was the only conception/strategy to construct the walking-backward gesture. Following this fixed idea, he had no idea that, in order to secure the proper use of the legs, correct mental guidance and control of the mechanism of the torso could be necessary21 and that all the work he had invested in trying to obtain a specific control of the neck and head had been wasted.

Any posture is the result of a concerted series of movements of the different parts of the torso in space.

The conscious guidance and control of the mechanism of the torso involves the guidance and control of each and every movement of the different parts of the mechanism in relation both to each other and to the leg and foot.

3. A Reasoned analysis on a reasoned plan

I started to ask him more questions so that we could analyse together his habitual strategy of organisation of the movements of the parts of the torso relatively to the movements of the limbs. I wanted him to see that he trusted a plan not really based on facts, nor on accurate words, and that his wish to move was in contradiction to simple mechanical principles. His conception of the actions necessary for performing the activity with poise was a preconception, i.e. a conception based on feeling sense experiences, i.e. a conception which does not involve any sound reasoning.

In order to step back, he ordered himself to place his foot back and, as a result of this conception, he was forced

- to make a one-legged stance and lift the whole swinging leg

- to bend the moving leg and stand on it while it was bent, i.e. walk “low”

- to swing the weight of the thigh backward (relatively to the torso and the target): this large momentum22, in a one legged stance, has to be balanced by an opposite momentum forward,

- to keep his balance as best as he could during the preliminary acts by moving his arms and upper torso.

The performance of the act as he was conceiving it was guided by the most naive plan of action: “make one step after the other” and the torso will somehow follow. The whole of the old series of movements which composed his gesture of walking backward had been correlated and compacted into one indivisible and rigid sequence which has invariably followed the One mental order that started the train23 “step back”.

He did not project a connected series of orders to the different moving parts to create a coordination aided and influenced by the force of gravity: he just gave the one order to move the foot back first and trusted his feelings, his embodied cognition retrained by many hundreds of modern Alexander technique touch-lessons, to bring him safely to his end and to accomplish his aim with impunity.24

It is also possible that his knowledge of the modern Alexander technique rule to have the head lead and the body follow was making matters worse: he certainly never reasoned out why Alexander (1938) recommended “Never let the head overrun the body [torso] in going backward”25 [with the torso]. On this subject and in on another occasion, I remember that a modern Alexander technique teacher retorted that the rule was not given for walking but for sitting, but, when asked if she had tested whether the rule could be extended to another activity involving the body [torso] going backward, she avoided answering and just maintained that Alexander had given the rule for leaning the body back in sitting (which is accurate but does not prevent anyone with an inquisitive mind to explore whether the rule could be extended or not).

The connected series of preliminary acts the young teacher performed in front of our eyes represented the subconscious means whereby he used to attain the desired end. He would certainly not have said that he “directed consciously” these preliminary acts, they just flowed from his naive spontaneous embodied decision to obtain the end proposed. His “means whereby” in the activity were not satisfactory26 because they were not reasoned out from the point of view of using the antagonistic muscular actions of the mechanism of the torso nor the force of gravity, and his solution did not depend upon the co-ordinated use of the mechanisms in general.

It must be said at this point that the young teacher, through no fault of his own, had been trained to associate Alexander’s “principle of the means-whereby” with a simple plan which involved no analysis of the connected series of preliminary acts which composed his gestures and no experiments whatsoever to direct rationally the connected series of acts he was doing with connected series of verbal directions stipulating the decisions he had to make in order to control that he was really projecting these concerted [simultaneous] decisions of movement in a mirror.

He had strictly no idea about this intelligent perspective. Perfectly in line with his training, he thought that the “means-whereby”, instead of a PRINCIPLE which serves as a basis for many different concrete approaches of corrective adjustments, all different and adapted to conditions, was instead a three-headed decisive RULE of thumb : (1) to make a stop before engaging into action, (2) to repeat to himself the same series of “directions” which meaning of which would have been revealed implicitly to him in his somatic training and (3) to refuse to do anything so that the words could work their mind-body magic unimpeded.

In this scheme, there are a few features that are worth noting:

- the only active factor of change is the touch-teacher, the provider of the experience which is supposed to reveal the meaning of the “directions” [neck free, the head forward and up and the back to lengthen and widen] with his touch,

- the means of change for the pupil is to FEEL time and again the effect of the teacher’s manipulations, so that “it”, that is the particular sense appreciation (feeling tones), becomes second nature or at least so that a subconscious reaction—feeling the right thing— can be conditioned into the verbal trigger of repeating the sentence “neck free to let the head…”

- the system of discipline, the system of (A) reasoning verbal orders which are adapted to a particular stage of progress, of thinking out the reasonable means whereby a certain end can be achieved, and (B) of obeying structural series of orders—translating into a physical manifestation a concerted series of instructions— is integrally replaced by the somatic credo of letting go, of releasing, of going with the flow, of trusting the intelligence of the “body”, etc.

When I look back at the times of my own training, it is true that none of us wanted the discipline, but the reason for that is that none of use were guided to experiment with it. It was as if it had never existed.

3.1. The means whereby plan

The young teacher’s performance of the gesture of walking backward involved the direction and performance of a connected series of preliminary movements which he ordered subconsciously, that is, without realising that

- he was doing this particular series of movements with the different parts of the torso and limbs,

- all the movements of the parts he was doing simultaneously were linked together27.

To give him a chance to grasp Alexander’s conception of the means whereby principle I needed to have him experiment at first hand the consequences of working with a functional system in which a change in the movement of any part means a change in the movements of all the parts: this is the only way to make him see that any attempt to eradicate a defect resulting from the incorrect guidance of a movement of a part otherwise than by changing and improving the faulty concerted guidance of all the movements is bound to throw out the balance somewhere else.

The short lesson I was giving him had the purpose of making him see these facts and start experimenting with the discipline of training oneself to act in accordance with series of orders of movements, the projection of which could improve his faulty use—the faulty connected series of preliminary acts he was doing— in walking backward.

The major principle which is conveyed by the lesson is that the performance of any act like walking backward, i.e. a gesture involving the whole self, involves the direction and performance of a connected series of preliminary acts by means of the mechanisms of the organism, and that he, the “pupil”, unaided, could become the expert manipulator who can command the continual readjustment28 of the movements of his own mechanisms29 (a continual readjustment cannot be done but by the subject himself).

The term “direction” refers to the reasoned instructions of movements which have to be concerted together to produce a particular spatial relationship between the parts. The term “performance” refers to a progressive translation of the series of orders into a series of preliminary movements of the parts and no other, where one is controlling whether the series of acts seen objectively is in accordance with the spatial plan defined by the reasoned “direction” of the gesture.

The term “mechanism” occurs very often in Alexander’s books: it refers to the combination of parts moving in a concerted way to produce the performance of a “general act” and of an associated functioning as a whole [good or bad] according to the laws of motion and equilibrium. If the act is performed with an expanded mechanism of the torso the functioning will be maximum, or else it will be detrimental.30

Have you ever heard something about the 2-circumferences rule of functioning or about its application in practice?

What is very surprising in a technique in which there is a solid written legacy is how totally the affirmations of the founder regarding the mechanism of the torso have been neglected and discounted by his own followers.

I am not saying that every rule proposed by Alexander should be followed blindly, but at least, when one particular rule regarding the working standard of efficiency of the self is clearly established in writing, it should be at least investigated, put to the test and contradicted, refuted or proven and demonstrated. Ask any modern Alexander teacher about the torso two-circumferences rule of functioning stipulated by Alexander in writing and you will find that they have never heard about expanding the upper torso circumference and contracting the lower torso circumference,31 or, if they have, that they simply regarded it as an old nonsense (peddled from Alexander’s past) which has obviously nothing to do with the modern technique focused on the release of the head and neck relationship.

The danger is of course, that if you start testing and controlling the effect of Alexander’s own rules, you may start to raise a discordant voice and find yourself isolated from the great unity of the different branches of the modern Alexander technique. For my part, to start with, I could not help but seeing that the two-circumference rule clearly resonates with the idea of series of concerted movements of the different parts of the torso and many other puzzling practical procedures which are spread in a mosaic way in Alexander’s four books.

To come back to the subject at hand, the understanding of the principle of reasoned means whereby depends on the realisation that the habitual unreasoned and spontaneous series of orders of movement to the different parts leads to a wrong use of the mechanisms—in particular the central mechanism of the torso and its circumferences— a wrong use which Alexander considered responsible for all the defects and symptoms, including the stiffness of the neck and the wrong axis of the head32. In order to work to principle to eradicate all defects, the student must be taught to act in accordance with a series of new instructions reasoned from the point of view of the working of the whole, i.e. reasoned instructions guiding and controlling the movements of all the different parts of the mechanisms, starting with the mechanism of the torso. The orders for a satisfactory coordinated use of the mechanism in general must be projected as decisions of simultaneous movements, i.e. in a coordinated series, to correspond with the connected series of preliminary acts reasoned as best for the purpose at hand. This is what Alexander is saying in the quote borrowed from the Use of the Self (1932).

As I have explained, the need of reasoned guidance33 has not yet reached the mind of the young teacher who still believes that subconscious guidance, i.e. embodied cognition and guidance by correct feelings experienced under the touch of a skilled touch-teacher, could allow him to improve his coordination. Exposing Alexander’s disturbing theory of the means-whereby, and of the demand that every human being shall be enabled to make the analysis between subconscious and conscious guidance to a longstanding somatic student is of little effect, but his reasoning may be reached by having him experiment with his own capacity of conducting the different movements of the parts of his organism in order to form a new “conception of how to employ the different parts of his mechanisms“.

“In our conception of how to employ the different parts of our mechanisms, we are guided almost entirely by a sense of feeling which is more or less unreliable. We get into the habit of performing a certain act in a certain way, and we experience a certain feeling in connexion with it which we recognize as “right.” The act and the particular feeling associated with it becomes one in our recognition. If anything should cause us to change our conception, however, in regard to the manner of performing the act, and if we adopt a new method in accordance with this changed conception, we shall experience a new feeling in performing the act which we do not recognize as “right.” We then realize that what we have hitherto recognized as “right” is wrong. (Alexander, F.M.; Constructive conscious control of the individual, Integral Press 1923, reprinted 1955, p. 83)

Most thinkers of the modern Alexander technique thought that they had found in this passage the shortcut they needed to argue in favour of their conception of the technique as a touch-centered somatic body-work. Alexander says that the act and the particular feeling become one in the recognition of the person working on the subconscious level. When the subject has associated an act with a wrong feeling, it seems at first glance that all that is needed is to make the subject experience a new “correct” feeling in relation with this act, for the association to work virtuously. Once the sleight of hands has been repeated sufficiently, the person should be guided by a “correct sensation” in this particular act.

Meanwhile, nothing has changed fundamentally in the sphere of guidance of the student after any number of repetitions of the sleight of hands: the person is still working at the subconscious level, under the CONCEPTION that she will be guided in the future by the feeling she experiences after the gesture has been performed. If the student experienced lightness as a result of the ministrations of the touch-teacher, she will try and move in the same way, i.e. “with a feeling of lightness”, and this is all she can do as she is totally incapable or reasoning out what are the concerted movements which produced such end-result. She has not been taught to work according to principle, certainly not according to the principle of the means-whereby.

What is NOT written in Alexander’s quote above is that when the global act is associated with a feeling, when an act and a feeling become one in our recognition, then it follows that we have correct guidance at our disposal. Alexander is saying just the opposite. This kind of feeling guidance could not adapt to new situations. The supposedly “correct feeling” is only valid for the very moment of the touch-lesson and, as soon as the pupil will start guiding himself with his own means, the correct feeling is going to be just a memory of a feeling experienced in the very strange conditions of being guided by the touch of someone else, at a certain time in the evolution of the coordination of the pupil. This feeling may be useful to guide the pupil during another touch-lesson with the same teacher, but it is totally useless to provide guidance in new normal conditions of life, when the pupil has returned to his old habits of use of the different parts of the mechanisms and to his old conception of how to employ the different parts, i.e. according to what feels right at that moment to him.

Alexander’s principle of the means-whereby is precisely to refuse to correlate and compact a series of movements into one indivisible and rigid sequence which invariably follows a mental order that started the train. The principle of the means-whereby rests on the reasoned analysis of the means-whereby acts, i.e. the analysis of the preliminary movements of the parts which make the performance of any act possible, and the controlled conditions of experiments to judge whether the subject can translate the series of orders designed to make the performance of the act possible along new lines.

What Alexander is also not saying in this quote bears on the trustworthiness and reliability of the new feeling experienced in performing the act in a new way which made us think that the “right” feeling experienced when performing the act in the old habitual way was untrustworthy. Both experience and theory plead in favour of the contrary, as muscles, tissues and cartilages which have been put out of action and which will brought back into play34 by the re-educatory method will certainly feel different—totally different most of the time— after a few weeks or days of appropriate work. “Time is of the essence” Alexander would say, meaning that no feeling of a motion of a physical part can stay unchanged in time particularly if the subject is following a path of change. Feeling cannot constitute a criterion to evaluate a process of change in real life conditions.

3.1.1. Realising the undeveloped condition of conscious guidance

My own analysis of the young teacher’s attempt at the unusual procedure of walking backward toward a target was that his way of “doing things”, i.e. the connected series of preliminary movements he did in his desire to move the limbs without any regard for the planning of the movements of the parts of the torso, was setting off a psychophysical disposition of the parts35 conducive to imbalance and lack of general equilibrium, physical and mental (which should have been the main focus of his reasoning mind in the knowledge of the future contact with the chair).

The young teacher did not realise that, as a result of his own unique decision of movement [move one foot back after the other], placing the middle torso forward in relation to the foot, he adopted a POSITION OF MECHANICAL DISADVANTAGE with the different parts of the torso in the carrying out of the particular piece of work I asked him to perform for us. Alexander would have said that the visual impressions left by his “position” of the torso in walking backward was characteristic of a chest well set and stiff, strutting like a pouter pigeon and the worst shortened stature he could imagine.

F.M. Alexander analyses his visual impression of the disposition of the different parts of the torso.

Despite all the alleged re-education of the feeling sense during his training course, the young teacher appeared not to feel the ill-considered arrangement of the parts of the torso that he was creating (“doing”) in walking in the way he did, any more than he was aware of his habit of projecting unconsidered and disconnected orders of movement like his foot back relatively to the torso among many others. All that was left of his guidance by the primitive mind of sense was the anxiety and uncontrolled impulses36 he demonstrated in coming close to the chair, as if he knew subconsciously that the had already lost his poise and that the least contact with the chair could make him fall backward. This kind of embodied guidance did not help him solve the problem he was faced with, but, on the contrary, it made the process of finding a solution unreachable because it focused him on feeling.

Following his own way, he had put himself so close to a position of dis-equilibrium as to be an easy prey for a backward stumble when stopped in his track by a chair-obstacle. His embodied solution to the task proposed was exactly ANTI-POISE and the difficulty he was experiencing was simply the result of “his way of going to work37“. His anxiety in bumping into the target was just a result of his lack of equilibrium in walking toward it: with a torso poised, had he walked fast backward and stricken the chair violently with the back of the leg, the chair would have flung in the air!

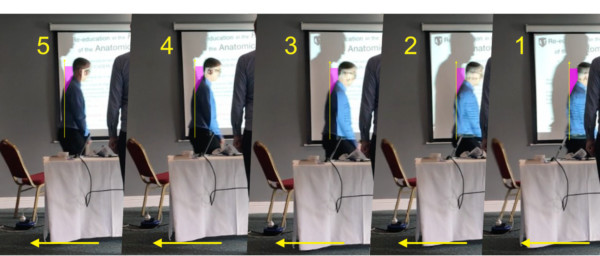

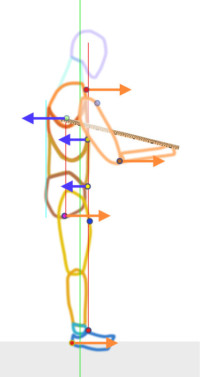

I demonstrated this reasoning for him in actual practice, making clear that if

- I obeyed a series of movements which resulted in an extended position of the torso and,

- forgot to stop after touching the chair with the back of the left leg, the chair would be projected back: a simple chair was no match for a poised torso of a grown man walking backward.

I showed him that in walking backward with a “POSITION” of mechanical advantage, the contact with the chair, even at speed, could not endanger the Poise, i.e. the dynamic equilibrium of the self.

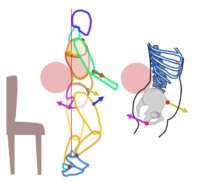

In walking backward with a reasoned direction of the series of movements of the parts of the torso, the contact with the chair does not alter the poise of the self and the chair simply is projected back in the air. The time frame of these five images is about 1 second in duration. The contact occurs at image n°2. During the whole event, before and after projecting the chair, the back is seen lengthening and the head is very far forward and away from the back.

3.1.2. A word of caution regarding the word position

I would like to offer a word of caution regarding the word “position” as it is employed here and in Alexander’s books. In his writings, Alexander employs the word “position” with a very unusual meaning for the Moderns who are fixed on the one-dimensional idea of opposition between the words “movement” and “position” in the common denotation of the terms.

The first modern misconception concerns the range of parts that the word covers in Alexander’s neologism: the position of mechanical advantage refers primarily to the mechanism of the torso and not to the “position of the limbs— arms, legs and neck— and torso”. This makes a critical difference: for example the expression “studying the position of mechanical advantage” gets a whole new meaning. Studying the position of mechanical advantage does not mean to maintain the whole structure “limbs and torso” into a so-called ‘fixed position’, but to explore the movements of the parts by means of which the torso can be deliberately expanded whatever the movements of the limbs. From standing to “monkey” to the “frog” gesture, we want to study how to command the movements by means of which the torso can be fully expanded without discontinuity.

In the procedure of the hands-on-the-back-of-a-chair, we want to study how we can control the means whereby movements which command the expansion of the torso in leaning forward38, in moving the arms39 and in pulling to the elbow away from the hands. From there it is also possible to start studying how the torso can be fully expanded when the different parts of the torso have to move rotationally (procedure of the “swing up and down in the same orbit”)40 relatively to each other. It will become obvious then that the “position” of mechanical advantage is not a fixed position, but the outcome of simultaneous adaptive movements of the different parts of the bony structures of the torso.

Alexander’s employment of the word “position” to mean the geometrical arrangement of the parts of the torso in a dynamic gesture [dynamic because it is composed of a series of opposing movements of the parts] is just another symptom of his habit of neologism (he takes a common word and gives it his own “new” meaning without explaining to his reader that there is a possibility of confusion).

In his books, I have found that Alexander writes about what he calls “the faulty standing position41” [of the torso] in walking, in leaning forward, in marching42, running, going downstairs, swinging at a golf club43, etc.

It is abundantly clear that F.M. Alexander is not employing the word “position”—which in his writing is clearly the “position of the spine”— in the trivial sense of an absence of movement, because maintaining a “position of mechanical advantage of the mechanism of the torso”, i.e. a harmonic expansion of the torso, in a moving gesture requires the constant adjustments of the different bony structures of the torso, with a series of synchronised movements to obtain the maximum expansion of the torso, despite the changing pulls of the limbs in the different attitudes.

I never found one instance of Alexander placing the concept of a still-position in opposition to the idea of dynamic gesture. All the evidence points to the fact that, for him, a position is just a still representation of geometrical relationships projected upon (abstracted from) the unfolding of a dynamic gesture. His theory is that, to adopt or maintain a position of a lengthening spine which he calls a position of mechanical advantage [because of its association with an expanding torso], a series of concerted movements is indispensable, all going on and converging to a common consequence44, i.e. the harmonic expansion of the torso. These movements, i.e. the movements by which the “position of the torso” is assumed are not fixed once and for all: they have to adapt to any conditions to maintain the different parts of the torso as close to the geometrical model of expansion as possible. To maintain a position of mechanical advantage, a lengthening spine, during a fast movement like swinging at a ball or conducting a ploughing cart in a sharp turn, it should now be clear that concerted movements of the different parts of the torso must be operating and evolve at each second to maintain the geometrical relation between the parts of the torso which guarantees its full expansion. Here we see that the common rule of the modern Alexander technique, “Keeping the torso in one piece” can be completely mis-interpreted as a prohibition of unnecessary movements.

Also, it follows from this demonstration that the position of mechanical advantage cannot be associated with a feeling, as it represents not an end result which is seen or felt, but the model of the actions which precedes execution of the actions.

In conclusion, as to maintain the “position of the spine“, in any gesture involving the whole self when moving one limb or another, a series of movements must be applied to the different parts of the torso, therefore F.M. Alexander’s conception of the word ‘position’ is not to be opposed to the idea of movement, but employed to represent an indication of the outcome of the synchronised movements which make the relative position of the parts of the torso in any gesture.

3.3. Placing the foot in that position which will throw the limbs and trunk vertically at each new step

It may seem that we are just concerned with the specific movement of a part at the exclusion of the movements of all the other parts. This could not be further from the truth, further from the means-whereby principle with which we work when faced by the unusual.

In the act of walking backward with the limbs and trunk aided and influenced by the force of gravity, the different parts of the torso must be moved first, and the foot second, the latter catching with the translation of the torso and future supporting limb, so that the whole structure can be seen supported by the foot which comes under the torso and leg already organised along the vertical line which we call “line of Oneness”.

This explains why the subject of learning the placing of the foot is in practice sub-divided in four different phases which I will expose in four different chapters:

3.3.1. Linking the movements of the arm with the movements of the parts of the torso

3.3.2. Disassociating the movement of the frontal plane of the torso from the movements of the limbs

3.3.3. Acting under the guiding principles of reasoned and conscious control

3.3.4. Linking the movements of arms and legs with that of the torso is the recipe for poise

3.3.1. Placing the foot in that position which will throw the limbs and trunk vertically at each new step

Instead of tackling the new problem [of a definite inhibition of the movement of the foot back] directly and have him repeat vain and unproductive attempts,

When a student is stuck with one particular direction of movement, would you think of adding more movements in his already crowded field of attention?

I chose to have the operator direct his attention on the disassociation-and-control of the movements of the parts of the torso relatively to the upper limbs. In other words, in order to give him the opportunity to explore a new way of walking, I decided to have him coordinate (disassociate-and-control) some NEW MOVEMENTS which were not associated with his conception of moving backward. I wanted him to have more objects in mind rather than less, to direct his gesture rationally.

The poverty of a gesture like walking backward is proportional to the number of the parts which are moved intentionally. The conception of the gesture of walking (forward or back) as “stepping with the foot” is contrary to the means-whereby principle as it does not involve thinking about a connected series of movements. Such an event is part and parcel of each lesson of conscious guidance and control and, after twenty years of experiments in this direction, I am very close to saying that the law of the dynamic wealth (Delsarte) or, in other words, the means-whereby principle of Alexander are indeed a law in the construction of intelligent motor acts.

I asked him to hold the extremities of two wooden rulers in his hands and to place the opposite end of the sticks under his armpits with his hands directed Forward in space. I explained that the spatial adverb ‘forward’ meant a direction ninety degrees to the plane of the frontward extremities of the ribcage below the sternum. Maintaining consciously the ninety degrees direction of the rulers to the rib8 line ensure that

- the distance between the extremities of the two rulers stays the same and,

- that one shoulder is not more or less extended that the other (as it is often the case in the incorrect movements of the parts establishing a scoliosis).

It is possible to represent the spatial words of direction relatively to the frontal plane of the torso. The ruler helps the student to calculate the direction and subordinate the movement of the arm to a geometrical rule.

All the words relating to spatial directions are defined relatively to the Rib 8 line on the frontal part of the mechanism of the torso. In the beginning, holding a ruler will help the student orientate and link the movements of the different parts of the limb in a rational way relatively to the movements of the different parts of the torso. Once the pupil is able to achieve the concerted movements, I will ask him to coordinate the same series of concerted movements without the help of the rulers.

Also, using two rulers will make much more concrete in the mind of the operator the concept of “following with the [frontal plane of the] torso as nearly perpendicularly as possible the line” of trajectory toward the target/chair (cf. the ploughing procedure).

I also requested him to direct the tips of the elbows outward and slightly downward, opposing the movement of the elbow with a movement of the base of the palm directed inward.

These orders of definite performance of series of movements may appear strange to a modern Alexander teacher but they are in fact an exact replica of the series described in the technical evolution [hands-on-the-back-of-the-chair] employed by Alexander to allow the pupil to experience the “due and proper amount of so-called “muscular tension” necessary at any given time in the arms without having to give any manipulative help46.

The description of a technical evolution from which these orders of movement are taken is the only testimony of what Alexander considered to be the “new directive orders” [in opposition to the “preventive orders47” which are “let the neck be free, to let the head go forward and up, to let the back lengthen and widen” and which should never to be carried out)] that the pupil should rehearse and in which the movement of the arms is linked up with the use of the other parts of the body [torso]48.

This “gentle forearm pull from the fingers” effected by the coordination of the two decisions —(a) the decision of movement of the *tip of the elbow* outward and down & (b) the decision to keep the hand directed forward with the base of the palm directed inward— would give the subject a way to link up the use of the arms with the use of the other parts of the torso.

3.3.2. Disassociating the movement of the frontal plane of the torso from the movements of the limbs

The idea of maintaining the movements of the arms and torso linked to a ninety degree angle, despite the fact that they are directed in opposite directions, has another purpose, that of considering another factor to be overcome: the fact that the walking trajectory cannot be guided by a feeling guidance as the target is hidden from view.

The solution I proposed is also derived from a practical procedure explained by Alexander in his books49.

Having in mind the orientation of the frontal plane of the torso is a perfect solution of guidance for a gesture which does not provide its target in direct sight: walking backward and driving a plough have this characteristic in common. Exactly the same as the subject walking backward toward a target, the ploughman must imagine where he wants the furrow to be, as the furrow is not yet made in the soil and as the plough and horses are concealing the ground in front of the team: he cannot feel where his general direction must be, but, as Alexander writes, he must “follow with the frontal plane of the torso as nearly perpendicularly as possible the line the [future] furrow should take“. Instead of trying to feel where the furrow should be, he must calculate (reason out) where he wants the trajectory to aim at, in pure spatial terms, relatively to the frontal plane of the torso. If the ploughman was to try and guide his next step by looking at his feet (and possibly to the side at the previous line of furrow he had made), he would have no possibility of dis-associating the movement of the plow from the movement of the torso and he would automatically trace a wrong trajectory. Having the back-walker organise the arms geometrically relatively to the frontal plane of the torso should help solve the major problem of walking backward in a straight line, at least in theory. This means that our back-walker would have to organise his frontal plane of the torso relatively to an imaginary line: what a surprise if he discovers by his own experiment that he can!

Previously, when the young teacher was making his backward steps, there was no way of preventing the lower part of the torso from rotating in the direction of the (backward) swinging thigh. Just a little discrepancy between the pulls of the two thighs on the pelvis was enough to deviate the walking trajectory toward the side opposite to the weakest side of the torso. With the new orders of movement starting with the definite inhibition of the movement of the thigh backward relatively to the torso, and with the intention of directing the plane of the frontal part of the torso in space, the conditions for the deviation of the trajectory should have disappeared.

An experiment was required to evaluate whether the theory could be sound or not. If it was found that the theory was sound, the young teacher would have to reconsider his conception of the activity of walking backward as a task directly centred on the direction and control of the mechanism of the torso (he would then start to realise that he could walk back with swinging the thighs back as long as he opposed the couple of movement with the movement of the side of the torso forward where the thigh was moving back).

3.3.3. Acting under the guiding principles of reasoned and conscious control

I started to give the young teacher a number of indications regarding the movements we wanted to refuse to give consent to (orders of definite inhibition) and the decisions of movements which were required and that we wanted to see him doing.

– Are the sticks touching the sides of your ribcage at the back when your hands are directed forward?

– Yes, they are touching the ribcage.

– Note that they will not be touching the sides of your ribcage at the back if your hands are moving toward the center. Could you think of the order: “I will refuse to let the hands wander toward each other” and could you look carefully at the rulers so that (a) they stay directed at ninety degree to the frontal plane of the torso and (b) any tendency to the incorrect movements can be checked as soon as they show themselves50.

– Could you label the contact spots of the ruler directed Forward against the ribs at the back: “Rib at the back of the armpit”?

– I see no difficulty having in mind the spots on the side of the ribcage.

– You could then decide to give consent to move the “Ribs at the back of the armpit” back in space relatively to the ankle. The order to give yourself could be “I will pull the *Ribs at the back of the armpit* back in space”.

He retorted quasi instantly:

– and I would most certainly fall over backward.

I said something to explain that,

- he would certainly [feel he would] fall backward but for a very short time if he remembered to move the foot back AFTER initiating the “fall of the torso at the height of the armpit backward relatively to the ankle”. He just needed to order the movement of the foot AFTER that of the torso and in this way he would catch the “fall” of the torso by placing the foot just under the torso so that the supporting leg and the torso as a whole could be vertical and aided by the force of gravity at the moment of contact of the swinging leg with the floor. Moreover, repeating this procedure would lead him to walk backward in a totally new way implying a co-ordinated use of the foot and leg with the torso as a co-ordinated support51,

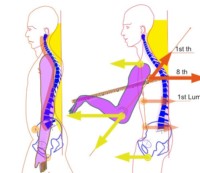

- that he could take a safety measure to make sure that the movement of all the weight of the upper torso, shoulders, neck and head would not go back at the same speed as the “Rib-at-the-back-of-the-Armpits”: because the bony structures of the thorax are articulated, he could have the middle torso go much faster back than the upper torso so that the upper torso momentum would not pull him back with the middle of the torso, but on the contrary would exert a momentum in the opposite direction. This would obviously result in a very marked change in the [relative] position of the bony structures of the middle and upper torso52, and he would not lead the gesture of walking backward with the head leading or the upper torso leading, but with the top of the middle torso going back faster that the upper torso and head.

This diagram shows how it is possible to conceive a disassociation between the movements of the upper limb from the movement of the middle torso.

The movements of the whole arm and torso can be dis-associated with the shoulders moving Forward and Down when the middle torso is moving Backward and Up. In other words, in the backward motion of the integral gesture, the middle torso would accelerate backward much faster than the upper torso, thereby implementing a very marked change in the relative position of the bony structures of the middle and upper torso.

If, at the same time, he was slowing down to a halt the swinging of the leg backward, he would indirectly slow down the movement backward of the sitting bones spots in space —the lowest part of the torso— and, thereby, move the sitting-bones Forward relatively to the middle torso to extend the whole thoraco-lumbar spine.

This was the theory underlying the new series of orders of movement which I wanted to see him perform. I wanted him to experiment to see whether this theory could be confirmed, i.e. strengthened by practice or not.

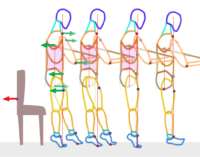

3.3.4. Linking the movements of arms and legs with that of the torso is the recipe for poise

I explained that “poise” could be understood as a concerted disposition of the masses of the parts and their momenta relatively to the vertical of the ankle of the supporting leg. By the term “disposition“, I meant the activity of conducting different motions of the parts in order to obtain a future alignment of a series of anatomical landmarks each time one step was made.

If he could make opposing movements of different “weights” relatively to the supporting ankle at the moment of contact with the floor, he would construct poise in action (poise is borrowed from the Old French, meaning a Weighing Scale with equilibrium between opposing actions of weights).

Is it possible to walk backward by keeping the rulers parallel to the walls on the side and making sure that the arms are moving backward at a slower speed than the middle back?

This diagram of the concept of poise is derived from Delsarte’s action coding system and his geometry of the “line of oneness“. The conditions of the neck and head (position and activity of the muscles) are consequences of the concerted movements of the different parts of the torso in relation to the bony landmark at the front of the (future) supporting ankle: this explain why there is no order of definite performance for the head and neck in this theory. When you stop doing the wrong thing [with the different movements of the mechanism of the torso], “the right thing does itself”, i.e. the head appears forward and up and the work will naturally devolve on those muscles intended to carry it out, and the neck will be relaxed unconsciously54.

I started explaining the safety measure which would allow him to organise some movements between the bony parts so as to create opposing “weights speed” forward when the middle torso movement backward was creating a force backward relatively to the supporting ankle. I asked him to hold the rulers fast and to see whether he could tell himself:

– “I will pull the tips of the elbows spots Outward [away from the center of the torso] and away from the hands, & Forward and Down relatively to the ribs at the back of the armpit“.

I waited for him to understand what geometry the instructions of movements could lead to.

I told him that this procedure is explained by Alexander in the description of the procedure called “Hands-on-the-back-of-a-chair” but that it is easy enough to do with any piece of wood, even when the hands are not connected together by a rigid beam of wood.

I showed him that in this way—by giving his consent to these movements— he could dis-associate the movements of the arms from the movement of the middle torso, i.e. move the shoulders [Upper-Part-of-the-Arm spots] Forward and Down, away from the movement of the Rib-at-the-back-of-the-Armpit spots going Back and Up in space during the actual dynamic gesture he was requested to perform. This linking/opposition of the movement of the arms to the movement of the ribs of the middle torso tended to be a means-whereby obtaining the result of the old instruction used by Alexander in the first training course “the upper torso comes forward when the back goes back55“.

Upon initiating what felt like the “fall backward”, he would order himself to pull the Rib-at-the-back-of-the-Armpit spots Backward and Upward away from the Tip of the Elbow spots directed Outward and Down and simultaneously to pull the Tip of the Elbow spots away from the Rib-at-the-back-of-the-Armpit spots, Outward and Forward”.

I gave him the new orders which would help him direct his mind in the proper way:

– I will pull the Rib-at-the-back-of-the-Armpit spots away from the *tip-of-the-elbow* spots, Backward and Upward, &

– I will pull the Tip of the Elbow spots away from the Rib-at-the-back-of-the-Armpit spots, Outward, Forward and Down.

He had to listen to the instructions quite a few times to start to make sense of them and to realise that, after a few attempts following which I detailed the wrong movements he had made in his first attempts [conscious control phase] that he should inhibit, he was perfectly capable of acting in accordance with the new instructions which tended to have him place the body [the torso] in a position of mechanical advantage.

The disassociation of the movements of the limbs, movements of the arms opposed to the movement of the middle torso and sliding movements of the feet on the floor, from the movements of the torso, ensures the equilibrium of the torso in the walking backward.

When I teach the series of movements necessary to obtain a new way of walking backward (poise in activity), I ask the teacher to go up on the toes and to rub the toes of the swinging foot on the floor as it moves back to catch up with the middle torso going backward. This provides help in two different ways: 1) it is thereby easier for the subject to inhibit bending the knee and rushing back with the foot and 2) the friction creates a shearing force directed forward which helps with constructing a forward momentum and produce an equilibrium against the horizontal backward thrust.

At the same time, I said that he could make the decisions

- (a) to inhibit lifting the swinging foot in the air and

- (b) to give instead consent to rub onto the floor with the sole or toes of the swinging foot.

It is not the place to explain here the mechanical principle of friction and shear as dynamic support system, but let’s just say that in order to inhibit the desire to lift the thigh and slow down the movement of the thigh and foot back, this is the perfect means-whereby order which will make a beginner capable of inhibiting the acceleration backward of the sitting-bones spots and prevent the inappropriate pull on the lower torso.

The habit of lifting the thigh is so strong and so firmly associated with walking that an antagonistic movement [rub onto the floor with the big toe] is essential to inhibit the movement of the ***Sitting-Bones*** spots Backward faster than the ***Iliac*** spots.

Even when the middle and upper torso are organised because of the new linking up of the use of the parts of the arms with the other upper and middle parts of the torso, the desire to lift the thigh and pull it backward will tend to shorten the hamstrings and pull the sitting-bones spots backward.

This movement of the lower part of the torso will inevitably increase the thoraco-lumbar curve, shorten the back and protrude the abdomen.

When the pupil will give consent to the instruction “I will rub onto the floor with the big toes when walking backward”, all these mechanical defects will disappear in the process.

4. Conclusion