Q1. I’ve been practicing adjusting my [movements] organization throughout the day and have been experiencing some resulting sensation in my abdomen which feels a little uncomfortable. Is this normal? Maybe I’m just not used to having my abdomen pulled back?

A1. Is it normal to feel a little uncomfortable? If your question is: “Is it normal to feel a discomfort amounting to irritation when adjusting all the movements of the parts of the torso and pulling the abdomen back? My answer is: Certainly Yes.

A1.2. Before we go on further, let’s review the model of the mechanism we are supposed to readjust.

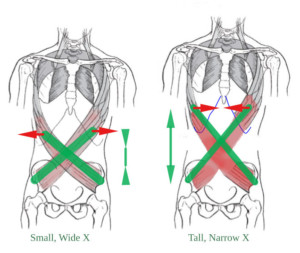

A new model for the mechanism of the torso: lengthening and narrowing an X

On this two diagrams presented below, the obvious difference between the two statures is the length of the structure, i.e., how far the upper torso is lifted away from the lower torso. We are going to reason how the movements of adjustment which lifts the upper torso away from the lower torso, i.e., “lengthening the torso”, must be aided by a readjustment of the bony structure of the lower ribcage from day to day. In this way, the series of adjustments we project during two seconds can continue on their own a long time.

At the same time, we are going to re-construct reasoned answers to these two questions: why should the lateral distance between the lower ribs narrowed and what explains Alexander’s indication that the muscles of the abdomen should be directly controlled to reduce a protruding abdomen?

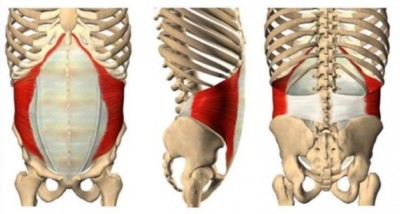

The imaginary “X” we are using to guide our decisions of movements is drawn on this picture by showing the internal and external obliques muscles which connects the ribs and the pelvis. (The X connects the ***Iliac*** with the opposite ***Ribs***).

When the X lengthens as a result of the series of preliminary movements you are giving consent to and which lifts the upper torso away from the lower torso, the [upper extremity of the] X narrows and the wide band of ligament sometimes called the rectus abdominis sheath (the Scarpa’s fascia), i.e., the connective elastic tissue in the center of the anterior abdominal wall lengthens and narrows. As it is attached to the transversus abdominis (trA), the latter is pulled toward the center. In this way, we will see that the transversus abdominis pulls laterally on the elastic tissues at the back: it widens the lower back.

Lengthening the X and pulling the belly back (especially at the moment of breathing-in because our unreasoned habit is to give consent to the opposite movements), are not movements synchronized consciously for cosmetic purpose, but to obtain a new widening at the lower back which will maintain the maximum expansion of the torso. I will explain the rationale behind this statement.

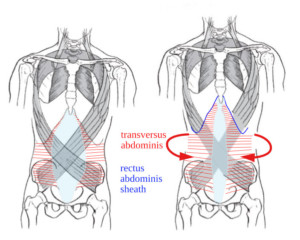

The transversus abdominis, innermost flat muscle of the abdomen, is attached at the front to the large inguinal ligament and the rectus abdominis sheath (the vertical white-blue band shown on the frontal view), the iliac crest, the costal cartilages (7-12), and at the back at the thoracolumbar fascia. The horizontal red lines drawn on these images indicate the direction of the pulls because they show the direction of the muscle fascicles. This diagram shows that, when the upper torso lengthen away from the lower torso, the rectus abdominis sheath will pull on the fibres of the transversus abdominis and widen the tissues at the thoracolumbar junction at the back of the lower torso.

Three views of the transversus abdominis during incorrect coordinated movements of the different parts of the torso.

When the upper torso is collapsed down by habitual movements, the central abdominal ligament is lax and wide (see picture), and the pull of the transversus abdominis is minimal. When as a result of habitual movements of the different parts of the torso, the lower back is forward and the upper torso back, as in the middle diagram sagittal view, we SEE Alexander’s “protruding abdomen1” and the undue lateral expansion of the [lower] ribs2.

The undue width given to the lower part of the chest which can be found nowadays in most pupils even when they do not practice customary breathing exercises (abdominal breathing) cannot be solved by lengthening or pulling the belly back in isolation. Both preliminary movements are necessary to slowly construct conditions of use which can become self-perpetuating and coordinated with the correct support at the back.

In these conditions, i.e., when the movements of the different parts of the torso result in this short and wide geometry, the antagonistic pulls3 synonym of good use cannot be obtained. These three diagrams show “bad use”, i.e., bad concerted movements of the different parts of the torso which result in a wide abdominal fascia (the upper torso is low), excessive expansion of the lower ribs and inefficient pull of the transversus abdominis on the connective tissues of the back.

It is only by giving consent to a series of movements by means of which lengthening the torso, bringing the back (lower back of the torso) back and the upper torso forward, that we can really experiment and measure the antagonistic pulls Alexander was talking about. When (a) the upper torso is moved away from the lower torso (pelvis), and simultaneously b) the thoracolumbar spine is moved back away from it (the old instruction “back back”, then c) the vertical band of connective tissue, rectus abdominis sheath, will narrow, and c) the combination of these three movements will stretch the transversus abdominis which will d) start pulling the connective tissues of the lower back to widen.

In most cases when the student has developed a strong habit of release (often synchronised with the breathing-in movement) it is necessary that he controls directly the muscles of the abdomen (“I pull the abdomen back relatively to the front of the pelvis and the front of the lower ribcage”) to help with the series of adjustment of the bony structure. The result of these concerted movements are not some distinctive feelings, they are not local, i.e., where the student is directing the movements, but global, as they change the gesture as a whole. Very often, when modern Alexander technique teachers and students come to that stage in their lessons, they do not understand why they are asked to give consent to so many decisions of movements: it is only by observing on video how they move as a whole in a gesture that they will realise what they have been able to achieve in terms of new integration and inhibition of unwanted movements.

This is the connection between the abdomen (transversus abdominis) and giant elastic connective tissue at the back

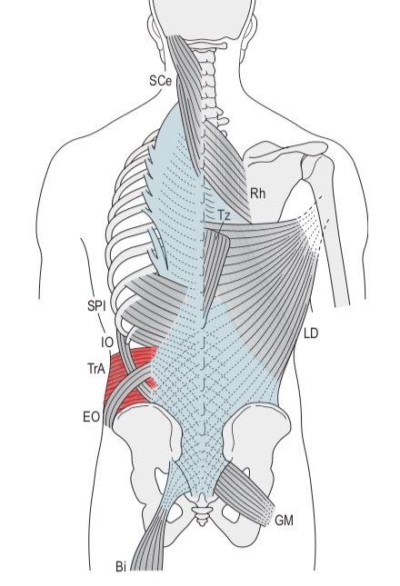

Now, there is a problem with the representation of the connection of the transversus abdominis with the thoracolumbar fascia in the previous diagrams. The problem is that the artist has only painted a smallest portion of the thoracolumbar fascia (in white on the back view). On this next image, you see that the other lateral extremity of the transversus abdominis (TrA) which is attached to the thoracolumbar fascia (in white-blue) connects in fact A) all the vertebrae from the pelvis (sacrum) to the head (cervical column) and B) all the muscles of the back of the torso and legs, by means of a large tissular structure of fiber reinforced elastic material.

This giant structure presented in blue on the diagram is the main organ of antagonistic pulls and its function is not local but general4 as it connect the top and bottom and the front and back.

The mechanical advantage of bi-directional pulls

Observe on the previous diagram depicting the thoracolumbar fascia the dotted lines which indicate the type of connective tissue which constitute this fiber reinforced structure. Single dotted lines indicate tendon-like tissues which transmit unidirectional pull; crossed dotted lines a different material transmitting and responding to bi-axial pulls. What looks like an unimportant feature will explain the reasoning behind Alexander’s strange assertion.5

When you inspect this diagram, you will certainly notice that the thoracolumbar fascia does not appear symmetrical as the dotted lines appear different on the left and right. This is just a consequence of the artist intention of furnishing as much informations as possible: the drawing represent the middle layer of the thoracolumbar fascia on the left and the superficial layer on the right.

You must understand that this elastic tissue only produces force when it is stretched and, as we will see, it produces more force when it is stretched bi-axially. This explains why I asked you to “narrow the X” and “control directly the muscles of the abdominal wall“: it is possible to go higher and for considerable length of time while producing much less “lift”.

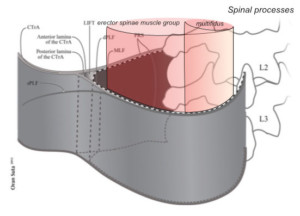

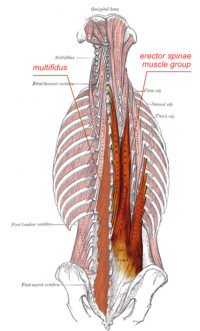

The thoracolumbar fascia envelops the deep muscles of the back and can play an important role in load transfer.

When the upper torso moves forward relatively to the lower torso, these paraspinal muscles resist the movement by lengthening.

First, you must realise that this fascia at the back of the torso is not a simple tissue. It is more like a tube (a sheath) which contains all the para-vertebral muscles. We will see that when that tube is prevented from narrowing in the middle when the back of the torso is stretched, the elastic resistance of the back to forward flexion is immediately strengthened without any recourse to active muscle force. Even a new student with weak muscles and fascia in his back will find that its capacity to sit and stand without strain increases immediately and steadily as a result of his giving consent to reasoned directions of bi-axial movements.

The thoracolumbar fascia envelops the deep muscles of the back and can play an important role in load transfer: when its elastic resistance to stretch augments, it will condition the functioning of all the extensor muscles in the back, particularly when they are called to resist to a flexion of the upper torso.

In all cases of kyphosis (excessive convex curvature of the spine as it occurs in the thoracic region), it is fundamental to restrain from any temptation to ask the pupil to bring the head higher and more forward and, instead ask the pupil to concert the movements of the front of the lower torso and abdomen (very far from the “problem of kyphosis or rounded upper back”), otherwise any stretch applied to the upper curvature will have no basis of support and will result in wasted effort and more curvature.

This sheath of strong connective tissue encloses or is attached to all the more important muscles of the lower, middle and upper torso. If properly used, it will strengthen and regulate the action of the muscles it encloses: with less contraction, they will produce three times more force.

Explanation

When the thoracolumbar fascia and its contents are stretched vertically, like any tube, it lengthen and narrows in the middle. Its cohesive resistant force becomes greater when the strain (deformation) augments, yet its elastic resistance must be sufficient to maintain elastically the momentum of the upper torso when its movement is forward relatively to the middle torso. This is seldom the case in our civilization of least effort and rest, because connective tissues respond to work —collapsing, lying down too often, the antithesis of work, deplete the fascia of its elastic resistance.

Nonetheless, it is possible to make this mechanism stronger from the start by using its geometrical properties, i.e., by creating a bi-axial pull out of reasoned directions of movements. This is exactly what Alexander must have had in mind when he wrote: “in reducing a protruding abdomen we can control many other muscles, notably those of the back, which when they are properly employed and co-ordinated will, by widening and altering the shape of the back, make place for the protruded stomach“.

I have tested this reasoning inside out with all my pupils and students, and no one has failed to see that the preliminary movements inferred from Alexander’s indications and models in his books are effectively producing indirect results of great value to maintain the lengthening of the torso in repose as well as in explosive gestures.

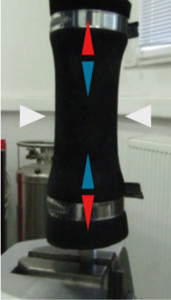

The following image on the left will give you first an idea of the mechanism of uni-axial pull. The red arrows indicate the pull of the machine on an elastic tube. The blue arrows represent the elastic resistance of the tube. The white arrows indicate the geometrical narrowing as a result of the stretch applied to the tube. It is easy to see that the vertical strain (cause) produces a narrowing in the middle of the tube (consequence).

When stretched vertically, and elastic tube produce a resistance proportional to the dimension of the strain

This image on the left represents a metaphor of the effect on the back of trying to lengthen by lifting the upper torso away from the lower torso without any narrowing of the X on the frontal plane of the torso.

Now, when as a result of concerted movements the abdomen is back, and the X at the front lengthens and narrows in the middle, the effect of the pulls transmitted by the transversus abdominis on the thoracolumbar fascia is the creation of lateral pulls which widens it laterally. This will immediately augment its elastic resistance as you will see on the next image.

This image on the right represents a thought-experiment based on the model presented on this opposite. It makes you imagine the new pulling force generated by the elastic tube (with the same vertical deformation) when a widening is obtained in the middle of the elastic material by way of a second series of pulls. What is termed bi-directional pulls is represented by the two sets of arrows, the first vertical and the second horizontal.

The vertical red Arrows indicate the same pull of the machine, but there is added lateral pulls on the elastic tube (horizontal red arrows). Now the vertical elastic resistance produced by the tube would be much greater than in the previous image (yet the vertical deformation is the same) because of the bi-axial effect: if the material is prevented from widening, its vertical resistance will increase immediately.

This bi-axial strain makes the resistance to lengthening of the tissues at the back of the torso greater both in the thoracolumbar elastic tissue and the paravertebral muscles it contains so that the upper part of the torso, the shoulders, arms, neck and head are kept from sagging forward at the front.

When the upper spine is that far forward of the middle torso, the upper torso and head are prevented from sagging forward and down by the elastic resistance (antagonistic action) of all the tissues (fascia and lengthening muscles) of the lower back of the torso.

Look at the picture of Alexander. What do you think is preventing the “hump” from collapsing forward and down, when the upper torso and the head are being moved that far forward (from the middle torso) when there are no muscle shortening co-contraction at the back? The “right thing does itself” because the geometrical conditions of the torso are directed by reasoned concerted orders of movement of the different parts of the torso and of the abdomen which conjointly create antagonistic elastic pulls.

Alexander insisted that the “upper torso must come forward” and “the [lower] back must go back“: this can now be understood has a way to produce movements of the parts of the torso which will load (stretch) the thoracolumbar fascia with no cost but incomparably less effort than the so-called released plumb line posture of the modern Alexander technique.

Directing the movement of the upper torso (and head) forward and up is a way to take advantage of the spring tissues in the back of the body. We load the elastic spring system to get elasticity and resistance. The belly uncomfort is worth it.

Q2. Or could it be that I’m pulling it in too much or holding it unnecessarily after the adjustment?

Any order reasoned out from the point of view of general coordinated use CANNOT BE USED IN ISOLATION

The pulling of the abdomen in order to help reduce the lateral distance between the *ribs8* is part of a series of orders of movements (lengthening the X) designed to widen the thoracolumbar fascia and help lengthen the back. It is also part of a series of orders of movements reasoned out to lift the upper torso away from the lower torso particularly designed to expand the upper torso in breathing in and out, and to allow the upper torso to come forward when the lower and middle torso are going back.

These orders have been reasoned out from the point of view of the co-ordinated use of the different parts concerned, and which therefore result in a co-ordinated gesture: the danger is to focus on one of these orders because it is the most salient and to give it too much focus. To make sure that you are not “pulling too much”, never make a specific adjustment, never pull the abdomen back if you are not giving consent at the same time to lift the upper torso forward of the middle torso and to direct a movement of the ***Sitting Bones*** forward relatively to the thighs…

We are working on the anatomical structure as a whole, intentionally creating the tallest cantilever beam possible (remember the explanation at the end of the presentation of the model above) to load the spring system of the back of the torso in order to take full mechanical advantage of the anatomical structure. It has been necessary to inquire as to why Alexander declares that it involves a direct control of the muscles of the abdominal wall (and as you know, I am not talking of release here) and I have tested methodically the reasoning behind these instructions of concerted movements.

Modern anatomy provides all the clues we need to understand the facts6 behind his hunch, but to pass from a theoretical approach to a deliberate practice the first requisite is to work as a whole and consider the “general adjustment” only as a series of concerted orders of movements or directions.

This is in total contradiction with modern Alexander technique understanding, in particular with the two opposite views of the teachings of Patrick McDonald and Walter Carrington.

Patrick MacDonald conceived directions as words to release a force which acts in certain ways and along certain paths.7.

Walter Carrington on the opposite scale conceived directions as words to pointer to the experience of release with [spatial] intention as one of his students John Nichols reported8.

To my deep regret, I think that by totally ignoring Alexander’s interest for definite movements and by setting instead the background for the word ‘directions’ in the somatic notions of force or release, these interpretations have led the modern Alexander technique into the total theoretical and practical confusion and into the cult-like transmission of somatic rightness that we know today as the “[modern] Alexander technique”.

After this explanation you will understand that pulling the abdomen back in isolation is an abomination. We are not interested in the FORCE you feel you need to put into it and even less in the feeling of release that you have been brainwashed to expect, but in the decision of MOVEMENT of the abdomen you are giving consent to perform with the other decisions of movements of the series. The force you think you need to put into the projection of the decisions of movements, and in particular, the facial and body expression you make because you are thinking of the force is of no interest whatsoever; the feeling of release that you associate with directing is not directing at all. All that matters are the movements, when you start them all, how they coordinate together and when you stop them ; these movements are not feelings, they are concrete events and you should SEE them on your motion video analysis.

What could be fruitful would be to inquire into what it is you are giving consent to when, after having projected your series of decisions of movement —including the movement of the abdomen backward—, you are seen to make quickly an extra movement of the abdomen which projects it forward, back where you feel ‘normal’..

Q2.1. Could it be that I am holding the abdomen unnecessarily after the global adjustment?

If the X is lengthened and you breathe keeping full thoracic expansion in and out, resisting the lateral expansion of the lower ribs in breathing in, the abdomen should stay back, more or less on its own after finishing your “three” (the conscious projection of the decisions of movements which constitutes the means-whereby of a correct use of all the parts of the torso).

Now considering the many years of release of the abdominal wall you have more or less unknowingly consented to, it is clear that the first few months of control of the muscles of the abdominal wall will feel a little uncomfortable until you gain sufficient elasticity in the tissues so that the lengthening of the torso will maintain the abdomen back. I must point out that Alexander gave that idea of direct control of the muscle of the abdominal wall as an example of the misunderstanding most people have regarding the concept of conscious control.

Therefore, provided you follow the recommendation of never concentrating on the abdomen only, it is acceptable to FEEL as if you are controlling too much as long as when you check on video your movements, you find that you are lengthening the stature and not collapsing on your abdomen.

Q3. Are you supposed to keep your abdomen pulled in or should you let it go after the adjustment?

After the adjustment, you should keep for a minute or more (see how long you dare feel that “wrong”) the geometry of “length and narrow in the front” associated with “length and widen at the back” of the torso. When you do, you will see (after a week or twelve) that your abdomen will tend to stay back on its own.

Footnotes

- “The marked lumbar curve of the spine with the usual shortening of stature and protruding abdominal wall. Harmful flaccidity of the abdominal muscles and general stagnation of the abdominal viscera”. (Alexander, F.M.; Man’s supreme inheritance, (Second Ed. Revised, 1918), p. 179).

- ‘The striking feature in those who have practised customary breathing exercises is an undue lateral expansion of the lower ribs, when several or all of the above defects are present, ‘This excessive expansion gives an undue width to the lower part of the chest, and there are thousands of young girls who present quite a matronly appearance in consequence. ‘The breathing exercises imparted by teachers of singing are particularly effective in bringing about this undesirable and harmful condition. (Alexander, F.M.; Man’s Supreme Inheritance (Third Ed., 1946), p. 167).

- “What this young lady is doing now is a very difficult thing to do. She is directing her head forward and up from here (Alexander indicates with his hands a part of her back), the knees forward and the hips back, and that the only way you can get your antagonistic pulls.

- “The TLF [thoracolumbar fascia] envelops the back muscles from the sacral region, through the thoracic region, and plays an important role in posture, load transfer and respiration (Gracovetsky et al. 1981, 1985; Bogduk & MacIntosh, 1984; Carr et al. 1985; Tesh et al. 1987; Vleeming et al. 1995; Barker & Briggs, 1999, 2007; Hodges et al. 2003; Barker et al. 2004, 2006; Schuenke et al. 2012; Willard et al. 2012). The TLF is comprised of three layers of which both the fibrous posterior layer (PLF -posterior layer of the thoracolumbar fascia)) and the middle layer (MLF) have a significant biomechanical function (Gracovetsky et al. 1981, 1985; Bogduk & MacIntosh, 1984; Carr et al. 1985; Tesh et al. 1987; Hukins et al. 1990; Vleeming et al. 1995; Barker & Briggs, 1999; Barker et al. 2004, 2006; Urquhart & Hodges, 2007; Gatton et al. 2010; Schuenke et al. 2012; Willard et al. 2012). The delicate anterior layer merely represents the thin transversalis fascia lining the deep surface of transversus abdominus and the quadratus lumborum muscles (Willard et al. 2012)..

- Alexander never expanded much on it and never explained how he had found this connection, but I have traced his strange advice back to Delsarte and the Bel Canto singers who knew about it.

- See in particular Vleeming, A; “In the present study, the biomechanical properties of the PMC [paraspinal muscular compartment created by the ThoracoLumbar fascia] were studied exclusively in the axial plane. However, the superficial and deep lamina of the PLF [posterior layer of the Thoraco Lumbar Fascia) acts as an intermediary in transferring loads in three directions: between the upper and lower limbs; between left and right sides of the body; and between the abdominal wall and the lumbopelvic spine (Vleeming, A.; The functional coupling of the deep abdominal and praspinal muscles, 2014)..

- “Giving directions, then, is not and cannot be the same for a new pupil as it is for one of a few weeks, months or years experience of the Technique. For the new pupil, directions start merely as words. These should be learnt by heart, in the proper order and they should gain in content with time, experience and the frequent application of a teacher’s hands. They must progress from being merely words to a release of force, which acts in certain ways and along certain paths. The words, therefore, turn into acts, but acts of a very delicate and subtle kind and these are not to be confused with the ordinary kind of activity which is commonly called “a physical act”. (McDonald, P.; On Giving Directions, Doing and Non-Doing, p. 2).

- John Nichols: “I don’t want to give the impression that Walter [Carrington] was denigrating the whole idea of giving directions. He taught us to direct, and, of course, you have to speak words to people to communicate, but I think from early on it was communicated to me that the words are pointers to the experience we’re aiming at. As we speak at this moment, I feel a little constriction around the back and sides of my neck. So I can take a moment to just ask myself to lighten up out of that, it didn’t require a word of any sort. There was a kinesthetic signal, a warning bell of discomfort, and then that combination of release with intention that we call “direction.” This was something else I very much learned from Walter: that there had to be muscular release but always including the direction you wanted the release to go in, otherwise gravity will just take all release into a downward collapse. Adding a directional intention to any release ensures that we get a redistribution of muscle tone, not a vague letting go of tension. Undoing of unnecessary tension— with appropriate lively tone for postural support—is “going up”.

Borrowing a term from the horse-riding world, Walter sometimes referred to this as “elastic bracing,” but not “rigid bracing.” So direction is muscular release with a directed spatial intention—terms like “wish,” “aim,” and “intention” work well. I often find myself saying to students, “Just keep this in mind as a quick wish or intention.” Or using a word Dilys [Carrington] often used, “Ask” for it to happen. But it doesn’t require repeating words in your head, as that simply adds to the noise. When you are teaching, of course you have to speak words to communicate with your students, but you are using the words to help them learn how to frame these wishes for themselves in an effective way, not simply to repeat your words to themselves. (Rootberg, Ruth; Living the Alexander Technique Volume II, Interview with John Nichols).